Some Names Associated with the History of Blackpool.

David and Maria Vero

Referring to the grave at Layton cemetery Blackpool, a little bit of research shows that both David and Maria Vero were from Dewsbury and both, it seems evident, possessed a committed radicalism to their causes. Dewsbury (Wiki) was a centre for radicalism and Luddite riots as industrialism grew faster than the society around it could cope, or care. David was working in a mill by the age of 14, and his brother, James, was also working in a mill at 12yrs old, so it can be assumed that David had started work at an early age, too. Both David and Maria would grow up with the aura of desperate dissatisfaction and the concept of the unfairness of working conditions and those inevitably bound within them. It would have been evident all around them and a compassion for humanity and a derived contempt for the injustices of life, would develop from there.

David Robinson Vero and Maria Brear were born in Dewsbury in 1837. On the 1851 census Maria was a scholar and her father a millwright, so the Brears were a little bit further up the social scale than the Veros whose pater familias was an iron founder and David and his brothers, mill workers. By 1861 at the baptism of his daughter, David is described as a mechanic and, on the 1871 census, he is working as a mechanic on a metal lathe. In 1911 David, who had been living with Maria in Blackpool for some years by now, after working away, is described as a superannuated member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers.

David Vero and Maria Brear married in 1860 in Dewsbury. A daughter Teresa was born in Batley in 1861. Though Maria is living at No 33 Exchange Street while David is still working in Batley, their address on the 1911 census is given as 35 Exchange Street, next door, when David had moved permanently to Blackpool (earliest date; 1906 electoral roles but their daughter Teresa married Alfred Heald in 1897 in the Fylde, so there is already a connection here).

Maria, so her gravestone states, was a member of the women’s suffrage movement. The Manchester branch of the movement was a hub of northern activity. She was involved from the earliest days of the movement when the final straw and the inspiration for women to get together and unite against the unfair domination of the male in society is demonstrated in the general reaction to the Contagious Diseases (Women) Act of 1865. Both David Robinson Vero and his wife Maria were active in campaigning for a repeal of the Act and its amendments, and held meetings at their Dewsbury home at Crossbank where Mrs Vero presided. The Act stated that women could be stopped, searched and even locked up without redress if suspected of prostitution. This was to protect men, especially the armed forces, against women and the spread of contagious diseases. Women were considered more dangerous than an enemy it would suggest. The Act was repealed in 1886 (Wiki). In her old age, Maria Vero may have been one of the suffragists harassed off the beach with violence by an unsympathetic crowd of both sexes at Blackpool in the summer of 1908.

In 1874 the Veros are also indicated in the celebrated case of the Tichborne inheritance. Taking the side of honesty, reason and fairness, they rallied against the forces of corruption and privilege in high places. The Tichborne case (a film was made about it in the 1990’s) involved the disappearance and alleged reappearance of Sir Roger Tichborne, heir to extensive estates. He had been assumed lost at sea but a man claiming to be him appeared back in England from Australia and made claims to the title and estates. Though he was able to convince the dowager Tichborne that he was her son, he had the demeanour and appearance of an ordinary man and that fact put him at loggerheads with the ruling classes in the ensuing court case. To others, then, just because he had been working as a butcher in Australia for many years it did not disqualify him from any legitimate entitlement and he became a kind of working class hero. The Veros come into it when the man was declared a fraud, sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude and his defence Counsel, Dr Kenealy, an eccentric character by all accounts, disbarred. In the Batley Town Hall, David Vero chaired a meeting to deplore a class system that had given an unjust sentence to the claimant and had resulted in the unfair treatment that Dr Kenealy had been handed out. The final resolution of this meeting reads, ‘That this meeting sympathises with Dr Kenealy in the unjust persecution to which he is now exposed and resolves to petition Parliament for the abolition of Gray’s Inn as a useless and corrupt institution.’ Extreme, no holds barred sentiment.

It was irrelevant whether the claimant was genuine or not, and there is still controversy as to his status, but David Vero, along with his wife Maria fought against perceived injustice with a religious fervour.

The gravestone also refers to a commitment to the Temperance movement, solidly adhered to by the heartstrings of some, vigorously opposed by others who reserved the right for the need to drink themselves to oblivion – or just to enjoy a glass or two of wine or ale. In the 19th century, Temperance was opposed by the (Liberal MP) owners of the celebrated Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the Blackpool area, and championed by the MP for North Lancashire, Wilson-Patten, whose successful Parliamentary Bill was ridiculed on one occasion by a Blackpool licensee, in an incident of ironic humour, and which would have made good material content for a situation comedy script in today’s world.

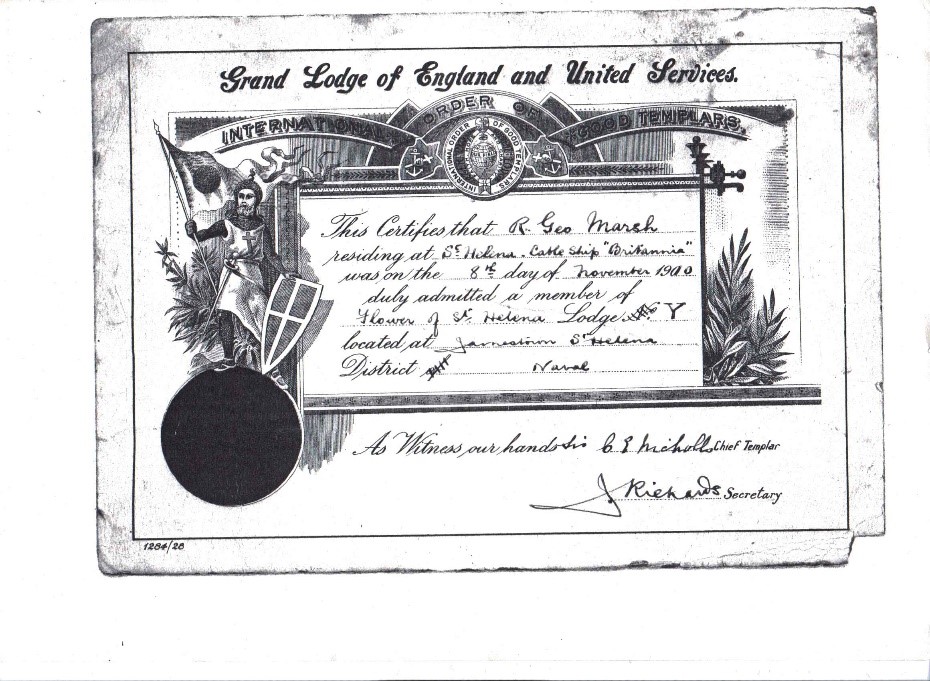

It appears that both David and Maria possessed some strong immunity to controversy, in which their heart strings were made of a strong weave. The reference to the Ancient Templar on the gravestone would no doubt relate to the commitment to the Temperance movement in particular to the Order of Good Templars, (instituted in USA 1n 1851 and established in England by 1870) and eventually a global society, which accepted women equally to men among its ranks. David and Maria Vero were involved from the very beginning of these movements for the cause of fair treatment and justice for all human beings. For the International Order of Good Templars, the only requirements for qualification as a member was a belief in God and an abstention from all alcoholic liquor and drugs. On the one hand this may be seen as being a party pooper, but for those who have witnessed or have been subject to the effects of the abuse of alcohol, as many women then and now have experienced, it would be considered sensible and rational. There was a deep, religious conviction in the movement without the need to belong to a religious denomination. Well, Christian denominations anyway, at the time. It would seem that both David and Maria possessed this conviction and exercised it throughout their lives.

My great grandfather in the above certificate was a member. He was from a background of severe naval discipline which ultimately resulted in the break up his marriage from which his wife and children returned to England from Capetown after experiencing the Boer war there. For some, yet unknown, reason Mrs Marsh chose to settle in Blackpool. She is buried in Layton Cemetery.

The censuses keep David and Maria apart. They are living together in Batley in 1881 but in 1891 David is living with his mother in Batley. Maria is not there. In 1901 he is boarding in Batley while working as a mechanic. Maria, in 1901, is described as a boarding house keeper at 33 Exchange Street. Her daughter and son in law Alfred are living with her. Next door at No 31 is Senior Vero and wife. Senior is a younger brother of David. It seems that David’s eventual retirement from full time work, allowed him to settle in Blackpool with Maria.

The gravestone at Layton cemetery reveals that Maria died Feb 20th 1913, aged 76, five years before she would have qualified to vote. David died 22nd December 1924 aged 88. Both were at 35 Exchange Street at the time of their deaths.

Their daughter Teresa, born in 1861 in Batley, married Alfred Heald in the Fylde in 1897. (Alfred was a Yorkshire man born in Holmfirth). She continued living in the family home of 35 Exchange Street and then, by the late 1920’s, can be found on the electoral registers along with husband Alfred. They have a daughter, Maria, born in Blackpool and the family line continues from there.

Sources

Any information that hasn’t come from newspapers or the gravestone itself, which I have visited myself at Layton Cemetery, has been sourced below. Where I have consulted Wikipedia, it is included in the text.

The verse on the gravestone is the last verse of a Temperance hymn, which can be found here;- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=blQEAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=endless+glory+will+your+useful+labours+crown&source=bl&ots=BhjX34qliY&sig=ACfU3U3qL9-n-IpqVEqoqacmNxsjNnLCvA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj3osbB4d3lAhVMiFwKHYC9ALIQ6AEwAnoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=endless%20glory%20will%20your%20useful%20labours%20crown&f=false

Further information on the International Order of Good Templars is sourced from here;-

https://archive.org/stream/goodtemplars00turn/goodtemplars00turn_djvu.txt

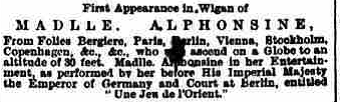

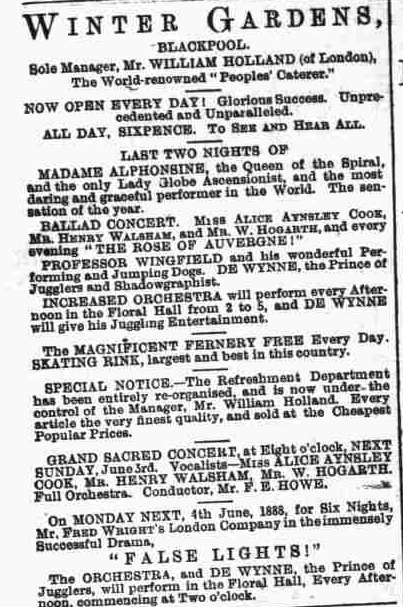

George Harrop General Manager of the Tower

Born in Oldham, George Henry Harrop lived at 77 Reads Road in 1911, with his wife and three adult children, one of who, George, was acting manager of the Grand Theatre at the time. He was general manager of the Tower from its inception in 1894 to his retirement in 1926. Before the opening of the Tower, he was secretary to the Blackpool Tower Company. He died at his home in 1938 aged 83. The stars he booked included names such as Music Hall artiste Vesta Tilley, and renowned opera singers, Clara Butt and Adelina Patti. He is attributed as the man much responsible for creating Blackpool as a classy entertainment resort.

The picture above is from the Era 1908

In the days when the licensing laws were much stricter and the Temperance movement stronger, he successfully applied for the bars to remain open on Wednesday afternoons (the former tradesman’s half day holiday), Saturdays during the winter, and extended hours for the Christmas period. Both music and dancing licenses were also necessary to apply for and he successfully saw these through, creating a venue where the sexes could deliberate to meet and socialise without necessarily having to go to a hotel or other drinking place. He also successfully applied for licenses for the performances of stage plays in respect of the Tower Pavilion and Circus.

In 1908 the entrance fee to the Tower was a tanner, or sixpence (6d), (less than 3p- when, a little later, the wages for a soldier in WW1 were 7d a day). It was a time when the advice from those from the deep industrial areas of the North who had experienced a visit was, ‘Tha’ll get t’best tanner’s-worth in t’world at t’Tower’.

His first job was to do battle with the licensing authorities to grant alcoholic drinks licences for the Tower facilities when completed. The Aquarium and the Beach Hotel were already on the site of the proposed Tower construction and had renewable drinks licenses in place. In 1893 as secretary to the Blackpool Tower Co, he argued the case for drinks licenses on the premises being transferred to the Tower from these establishments when it had been completed. A place to be used purely for entertainment was normally considered unsuitable for a drinks licence as these were only usually granted for hotels and those places which offered accommodation. George Harrop had to argue his case against this opposition. There were only six other places in Blackpool which had licenses and which at the same time didn’t offer accommodation. Drunkenness in the town was on the increase and 331 people (320 on the streets and 11 in licensed premises out of which, 276 males and 46 females had been convicted), so he had to convince the authorities that alcohol at the Tower would not lead to an increase in these figures.

In 1908 a reporter from the Era, the showbiz publication, was given a tour around the building, and was informed by the manager, that the most popular comment expressed by those entering the Tower was the great variety of entertainment provided for the paltry sum of sixpence.

The structure was lit up by 16,000 lights and 130 large arc lamps and a spotlight at the summit. Much of the gas that the Tower needed to drive its machinery was produced on site, but it was also the largest consumer of town gas in the town as electricity was still in its infancy. (At the time the town’s gas was produced at the gas works on Rigby Road).

The reporter was then taken up from the basement to the circus itself, with a capacity of 3,500 and was already of some renown in its young age. A variety of entertainment was on offer which included the clowns, Bob Kellino and little Pim-Pim, who appeared to be great favourites especially with the young, and there were also the musical clowns, the Brothers Webb. To the background of the orchestra, there were acrobats and skilled cyclists, horse riding, animal training, mules, monkeys and dogs, all trained to entertain with humour and skill. George Harrop is claimed to be the first person to bring the celebrated lion tamer Herr Seeth to Britain in 1894 where his acts with his lions and other beasts were performed within a cage which rose up into circus arena for the performance.

Herr Julian Seeth was Swedish and, somehow, was a friend of the king of Abyssinia and from whom he had received some of his lions. He had a strong and imposing physique and had trained over 300 lions during his time. He was renowned throughout Europe and so it was quite some coup for George Harrop to get him to Blackpool before anywhere else in Britain. There is always an element of cruelty involved in moulding wild animals to the whims of humans and in 1905 Herr Seeth was fined £2 and costs at Nottingham for cruelty to a pony which had been turning the merry-go-round upon which there were several lions. It is not recorded whether the lions were enjoying themselves or not, but one of them had had enough and leapt off to maul the pony enough to have to put the poor equine down.

It wasn’t the only accident as, in Blackpool itself, while after-season alterations were being carried out at the Tower circus in September of 1898, a joiner involved with the work was mauled by one of the lions, all of which had been allowed a free run within a railed off area. The joiner had had the misfortune to lean on the railings and the lion from within grabbed him by the arm and then the neck and face. Fortunately there were folk about to help and, by ripping off his jacket, they were able to release him.

But the more sedate entertainments continued in their variance and included a swimming tank, where the swimmers exhibiting this season of 1908 were the Finneys. Swimming exhibitions were a popular form of entertainment and were not to be denied the progressive entertainment of the popular seaside resort. They were an excuse for the men to ogle at the scantily clad females in their somewhat tight fitting costumes, and later on, to collect the cigarette cards to hide in the pockets. Less obvious than a telescope on the foreshore. And they were also an opportunity for the women to outwardly demurely, but no doubt with inner keenness, admire the Linford Christies on show, which was a delight denied in the usual cover-up of ordinary Edwardian day costume.

Further upstairs, the reporter was taken next to the Aquarium in which he marvelled at the world-wide variety of fish represented there. Climbing more stairs from there, they passed the silver model of the Tower presented by the shareholders to John Bickerstaffe, the chairman. Further along were cages of exotic birds. Anathema to today’s public, but spectacular in their relevance to the times, the Cape and Abyssinian lions, cheetahs and the monkeys were confined in their cages. Up more stairs and the reporter enters the roof gardens. In one of the ‘cosiest and prettiest retreats imaginable’, there is a profusion of exotic plants. At one end of this is a café where, while eating, musical entertainments and comedy could be enjoyed.

In another part of the building was the Old English Village, (which had a drinks licence) but the reporter was more interested in the fact that it was to be pulled down during the winter and replaced with a Chinese Town to be designed by Frank Matcham at a cost of £10,000. George Harrop and the reporter then took a trip in the lift to the Tower top and marvelled at the extensive view to be had and then their itinerary took them to the Pavilion and ballroom.

Here the more exquisite entertainment was on offer, for which a higher fee was paid for entry. 1/- and more for the upper balconies. He was entirely responsible for bringing, Clara Butt and Vesta Tilley, household names of worldwide fame, to Blackpool and both contributed to recruitment and the Red Cross during WW1. Vesta Tilley would take to the town to heart and eventually marry Walter de Frece, the theatrical impresario, and later, by her encouragement, MP for the town.

George Harrop retired in 1926 and Harry Hall, who had been manager of the Grand Theatre, took over the managership. He died at home on 14th February 1938. He was 83 years old.

Sources

All information above is directly from newspapers (British Library via findmypast) and from the census returns.

JOHN BICKERSTAFFE

Sir John Bickerstaffe died of a sudden heart attack at his home, Highlawn, on Hornby Rd on August 5th 1930. He was 82 years old and had been ill for a while, but had seemingly recovered and had recently been able to drive his car and visit the Tower offices. Only a week earlier he had been at the town’s aerodrome to welcome the King’s Cup winner, Mrs Winifred Brown. By fortunate coincidence both his only son Robert, normally resident in Liverpool, and daughter Mrs Fleetwood Parkinson over from Capetown to visit, were present at the time of his death.

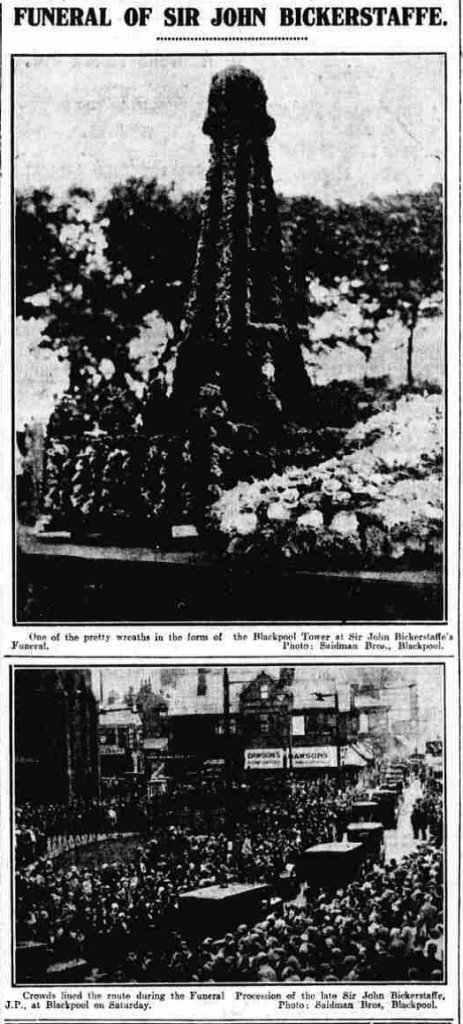

The funeral took place on Saturday 9th August and the cortege left Sir John’s home at 10.30am with its ultimate destination of St John’s Church where the service was conducted by Rev Little, a close friend of his. Between his house and the church, the cortege first proceeded to the Promenade where it paused outside both the Tower and the Palace Hotel with which he had been intimately involved. At these venues as well as at the Clifton Hotel, there were tributes to the ‘Grand Old Man’ of Blackpool or just ‘Mr Blackpool’ and outside the Tower, the whole of the staff gathered to salute his passing.

Every local authority was present at the funeral as well as every public organisation and there were over 200 floral wreaths, and that representing the Tower from the officials and employees of the Tower Company being six foot high. In a deferent tone, the wreath from his chauffeur, Dixon, was inscribed with his regular nightly words to his employer descriptive of the domestic scene of the times, ‘The fire’s dying out, the water is nice and hot, the windows and doors are bolted, the mouse traps are set, and there are no mice, goodnight Sir John.’

The funeral had taken place on the same day as the Blackpool Victoria Hospital Flower day and, in the days before the NHS, it was one event of many to attract funding to the Hospital. An anonymous gift of £1,000 (£66,843.93 today) was given reportedly by a friend of the deceased on behalf of the deceased because John had always given generously to the hospital.

His story is as one of the pioneers of Blackpool, being born, along with his brother Tom, in a tiny whitewashed cottage in Caunce Square, in the area that is now Hounds Hill in on January 20th 1848 when Blackpool was only a collection of a few houses and cottages and wasn’t yet a civic authority.

Both his father and grandfather made a living from the sea and John and his brother first made their money by taking visiting ‘gentlemen’ out on boat trips. With the first expressions of an entrepreneurial spirit, he bought some land fronting the shore to build a boatyard to increase his business as the railways were bringing holidaymakers to Blackpool in their droves. He was however encouraged into making a living out of Blackpool as a holiday town, as it became evident to those with entrepreneurial spirit and capability, and in the place of the boatyard he built the Wellington Hotel in 1851.

His cousin Robert was the coxswain of the Blackpool lifeboat, the Robert William, and John was ever present to assist as a member of the crew going out on many a daring rescue and was present on at least four notable incidents. The first of these incidents being that of the brig St Michaels in the September of 1864, the lifeboat’s first call, when John would have been only 18 years old. The French barque had lost its direction and had dangerously anchored by the Crusader bank and would have been wrecked at the turn of the tide but, with the help of the lifeboat and a couple of sailing vessels from Fleetwood, the ship was escorted to Fleetwood, its ultimate destination. At the time 10,000 folk cheered out the lifeboat and cheered its way back in after three hours of strenuous work by the crew. Later on in 1886, John nearly lost his cousin, when Robert was washed overboard from the lifeboat during the unsuccessful journey to locate the missing and ill-fated St Anne’s lifeboat which had gone out to respond to the distress of the Mexico off Southport.

Regarding the creation of Blackpool Tower, the popular story of John Bickerstaffe’s epiphany at the foot of the Eiffel Tower is somewhat apocryphal, it is understood. It is more understood that he was invited to join an enterprise to create a Tower in Blackpool to reflect that of the one in Paris and John agreed, putting his energies and his money into it, and history reveals its ultimate success which hadn’t been achieved without his own, determined vision and personal financial risk.

He had married Eliza, daughter of James Gerrard an innkeeper of Glasson Dock, in 1876 at Christ Church Glasson Dock and he first entered public life in 1880 at the age of 32 when he represented Brunswick Ward as Councillor until made alderman in 1887 and he served two years as mayor from 1889 after which he was embroiled in keeping the ownership of the Blackpool Tower Company in Blackpool and out of the hands of a London consortium. He was Conservative and Imperialist by conviction which suited his capitalist proclivities and which lent a hand to his ultimate success though not without a dogged determination. As a Conservative he was leader of the party and its chairman, and chairman off the Wainwright Conservative Club which he saw built. During his mayoralty he inaugurated the foundation of the Victoria Hospital, a necessity brought about by the town’s inability to respond with medical care to a disastrous railway smash at Poulton, and was on the Board of Management. By 1897 he had also established the Fylde Water Board, being a member until his death. He was chairman of the Parliamentary committee, arguing through and presenting several Town Improvement Bills. He was also chairman of the Advertising Committee and from 1907 he was the Blackpool representative of the Territorial Association for West Lancashire. As a young man he had been one of the first members of the Blackpool Artillery Volunteers and had won prizes for shooting.

His private, business activities included at one time or another, chairman of the Clifton Hotel Company, the Crystal Mineral Water Company, the Blackpool Passenger Steamboat Company (which included a steamboat called the Bickerstaffe), the Raikes Hall Estate Company and the Blackpool Electric Tramway Company, a first for a town in England. During WW1 he was chairman of the Recruiting Committee and of the Voluntary Aid Committee, and representative of the Military Service and National Service and West Lancashire Territorial Force Association and on the Local Advisory Committee for the post war resettlement of Labour. He was also honorary vice president of Blackpool Football Club.

He appears to have been a man who was able to confidently stand his ground in argument and often contended the views of the vicar of St John’s (Rev Balmer at the time). John was in the hotel trade as a licenced victualler through which he made much of his money, and arguments against licensing the sale of alcohol from an abstentionist viewpoint did not hold much purchase in his enterprise. For his arguments with the vicar in the pulpit, he was colloquially referred to as ‘the Rev’ but there was no bitterness in the rivalry, just a difference of interests. His public generosity included a gift of £1,000 (£120,458.33 today) to Victoria hospital on the coronation of King George in 1911 and previously £1,500 (£201,697.67) to the England Victorian schools which commemorated the Queen’s jubilee and he had also donated land for the recently opened Stanley Park.

In 1905 he had been made a magistrate and later a County JP and in 1912 was granted the title of Freeman of the Borough and he received a knighthood in 1926. He was a man that liked to mix in public and regularly walked around the town in his daily routine to and from the office, and shopkeepers would set their watches to the minute by his unchanging regularity. By the time of his death, he had been a member of the Town Council for nearly fifty years and a director of the Tower Company since its inception in 1891.

After his death, the current mayor, Councillor Gath, was appointed to alderman to fill the position vacated by the death of John Bickerstaffe. John’s brother Tom, already chairman of the Winter Gardens Company as the Tower Company had taken it over, was appointed chairman of the Blackpool Tower Company, having been on the Board of Directors since 1911. John’s son Robert Gerrard Bickerstaffe was appointed to fill the contemporary vacancy on the Tower Company’s board.

Fleetwood Chronicle 20th August 1930

His estate gross was £108,424 (£7,247,486.34) another newspaper report has it as £178,834. The executors are his only son Robert in Liverpool and two sons in law, John Winder and Thomas Harrop. He had requested that the solid silver replica of the Blackpool Tower, which is still on display at the Tower today and presented to him by the Blackpool Tower Company Ltd., should go to his son with the understanding that it should remain in its position in the Tower, or a similar position within the building. His son would also receive the silver engraving containing the Freedom of the Borough along with the illuminated scroll presented to him by the Borough.

He seemed to have been showered with silver gifts during his years as ‘Mr Blackpool’ and in his will he left them in equal shares variously to family members which included his children, Mrs Elisabeth Constance Winder in St Annes, Mrs Edith Mary Harrop in Blackpool, Mrs Lindsay Robinson in Lytham and Mrs Fleetwood Parkinson resident in South Africa, and unmarried daughters, still living at home and also his grandchildren, the family solicitors being Ascroft Whiteside of Birley Street.

Many streets are named after local folk, usually men, who have had an influence in the town and the Bickerstaffe name is now represented in the modern development containing the Council offices in Bickerstaffe Square.

All images are copyright British Library Board and the account is almost exclusively from the British Library newspaper archive via findmypast. Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

The Bank of England inflation calculator has been used for all amounts relevant to 2020.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

November 6th, 2019

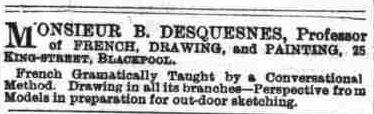

Benoit Desquesnes

Referring once more to the graves in Layton cemetery, research shows that Benoit Joseph Desquesne(s) was born in 1821 in Maroilles, Northern France and lived in Valenciennes also in northern France. He had studied art and sculpture in Paris and was a founding manager and democratic-socialist leader of the Valencienne Economique co-operative based on socialist models developing at the time and, more specifically, on that of Lille in the locality. This socialist model appears to involve a certain amount of mutual collectivism, co-operative and profit sharing, but it didn’t prosper as well as others.

He lived through revolutionary times and would have experienced the 1848 Parisian disturbances and the election of Napoleon 3rd.

In 1852 with the coup d’Etat of Napoleon 3rd (December 1851) who, reflecting modern day US politics, didn’t want to relinquish power, so took hold of it anyway dispensing with the election process and proclaiming himself Emperor, Benoit, as political opposition, was arrested at home along with his ‘concubine,’ Mirande – presumably the woman he was living with at the time, and probably of equal intellect and aspirations. On his arrest, the list in his possession of 153 shareholders of L’Economique was confiscated and the politically undesirable L’Economique was shut down. Benoit was given a six months prison sentence for belonging to a secret society and no doubt all the names on the list received a visit form the arresting authorities.

Benoit was just one of thousands who possessed political views opposed to Louis Napoleon and who were arrested and exiled or imprisoned. Others, including Victor Hugo, fled the country.

Benoit’s prison sentence left him financially ruined and he departed France for a statutory ten year exile in England where he settled in London and first appears in the Westminster rates books for 1858.

London was a collection point for many exiled Continental Europeans who took refuge on the more enlightened soil of Britain and there was much mutual help and assistance to be found among them. Several political anti-Napoleon organisations formed in London to continue the struggle against the regime in France and Benoit Dequesnes belonged to this movement. These diehard anti Napoleons were known as the Quarante-huitards (the 48-ers’) referring to the legitimate electoral system by which Napoleon was elected in 1848. The International Association, which existed in London from 1855 to 1859 and which was founded by French, Polish and German refugees and English chartists, was one of these. This Association can be regarded as the first international organization of a proletarian and socialist character and it is difficult to imagine that Benoit was not involved in it in some way. In London, Benoit, described as a local démoc-soc leader from Valenciennes, received commissions not only to paint individual portraits, but to assist in the sculpting of the decorations for the Crystal Palace. Much commissioned work came from France and since there were many French craftsmen and artisans in London some of this work was naturally consigned to them, unknown to the French authorities. Benoit was one of those sculptors and, in a consignment of busts (of the cephalic kind), of the French Empress Eugenie, he placed seditious material inside these creations before they were then exported to his homeland. It was one way of many in getting propaganda back across the channel and there would be many subversives keen to get their hands on to them.

Ironically perhaps, both Louis Napoleon (who was the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte) and Empress Eugenie, both found sanctuary in England until their deaths after fleeing from their own overthrow in 1870.

Benoit was also actively involved in Freemasonry, perhaps a continuation of his French activities, and it doesn’t take him long to become established. As new Lodges developed they were subject to conflicting ideas. With ancient Egyptian and Greek imagery there were friends and enemies of these conflicting ideas. If Benoit was a friend to one name, he was also an enemy to another name which included notables such as Alexander Dumas.

While in London he married Elisabeth, Canadian born and no doubt comfortable with anything French, and they had a son, Ernest.

On the 1861 census he accommodates a fellow artist and painter, Alfred Mirande as a lodger and whose surname reflects that of the ‘concubine’ arrested at his home in Valencienne in 1852. Perhaps this female, denied a Christian name by the report of the arrest, is the sister of Alfred but anyway most likely related in some way, directly or indirectly. Benoit has established himself in work as a house painter and is employing three men and a boy.

Benoit continued as an active intellectual and an artist by profession. He eventually settled in Blackpool and lived at 25 King Street where he taught drawing and French at the College House School, Queens Square.

He was active in politics of a socialist nature, accepting the complexities of including the mass of the population into the political equation a continuation of political ideologies while in France. He would have come across as a friend of the working man (and woman) when he claimed that, in calculated demonstration, that drunkenness and consequent violence increases when the distribution of public houses is less than more. The more pubs the less drunkenness. He would have been around during the construction of the Veevers Arms over the road, but not at its current demise. Of course, it was only topic discussed in the Blackpool Literary and Debating Society which met periodically at No 6 Queens Square, home of Councillor Marsden. Free speech, free trade, the openness of politics and Parliamentary reform in objection to the limitations of the arbitrary decisions to officially close Parliamentary debate at a whim, running scared and potentially losing the argument with continuing discussion.

His Frenchness didn’t leave him as in 1891, shortly before his death, he was elected honorary president of the Societé Francaise du Fylde which held weekly meetings, on this occasion at the house run by the Misses Lord and perhaps appropriately called ‘Rougement’, on Adelaide Street .

Mrs Desquesnes meanwhile, like all women, prominent on the ground but not worthy of a mention except for putting on a good spread for the men and only included in the usual numerous toasts after the ale or wine had been consumed in reasonable quantities, was a competent pianist and was present at Church meetings which included other prominent folk. At the Unitarian Free Church on Banks Street, which as an annual event, it was presided over by Mr And Mrs Laycock, of Lancashire dialect poet renown (and also in Layton Cemetery). In 1886, at the same Unitarian Church she was back on the piano to entertain among others, including Samuel Laycock himself who recited a couple of his poems. It was a gathering arranged by the Ladies Sewing Society, to welcome back the minister of the church, Rev F Haydn Williams from the Isle of Man.

In 1882 while in Blackpool he received a pension from the French Government as a former victim of the Napoleonic coup d’Etat of December 1851, though he had reportedly declined a pardon from the French Government because it wasn’t he but Napoleon who had been the wrong doer.

He eventually began teaching private lessons from home, charging half a guinea (about £65 today 2021).

In 1888 he wrote and published a brief autobiography in Blackpool. (Esquisse autobiographique d’une victime du coup d’état du 2 décembre 1851). I think there is a copy of this in the British Library.

He died on the 2nd of June 1891 and his wife Elisabeth is the administrator of his will. He is buried at Layton Cemetery Blackpool. The funeral took place from his home and the first carriage in the procession was a brougham, a higher class of Victorian carriage in which

His son Ernest born in London in 1858, and described as of Huguenot descent, qualified as a solicitor and, after his marriage, lived in Cheshire. He was actively involved in Liberal politics and intellectual circles originally in Blackpool. After, at first, unsuccessfully standing as Council candidate in Salford he succeeded by 16 votes (out of over 1,000) in the election of 1889 and eventually, from Councillor graduating to prominent alderman, was elected mayor of Salford for 1913-14. He had graduated from both Victoria University, Manchester and Paris University and passed his law qualifications in London in 1881. He married Janie Tottie in 1887 and had a son, Arnold and a daughter, Jeanette Betty (Nanette). He was a Liberal in politics and he delivered several speeches to the Blackpool Liberal Club on English land reform and the Irish Land question and lectured at several venues in the town on differing political angles and personalities. At a meeting of the Blackpool Literary and Debating Society in November of 1881, the motion put forward was, ‘That Conservatism properly understood in theory and rightly developed in practice is the highest political wisdom.’ Ernest Desquesnes with his Liberal political bias countered with, ‘That Conservatism as it really is, in theory and in practice, is the narrowest unwisdom.’

In 1906, in reference to the Unemployed Workmen Act of the previous year, he was Chairman of the Distress Committee. He was actively involved in War relief in Manchester during WW1 while Elisabeth was also involved in social issues in the City and was president of the Salford Ladies War Committee. in 1884, now working in Manchester as a solicitor, he was presented with a marble timepiece for his association as President of the Blackpool Literary and debating Society at an evening’s dinner at the Victoria Hotel in the town.

His son, Arnold a solicitor also, was injured during WW1 as Captain Desquesnes of the 8th Lancashire Fusiliers. As Lt A Desquesnes he is listed as either missing, injured or invalided in the Manchester Grammar School magazine for 1917. Benoit’s daughter Nanette married into Italian nobility in 1915 and worked with the Red Cross in Sicily during WW1. The family of her husband, Aldo Jung fighting on the Italian front was from a Palermo family.

In 1944 Arnold Desquesnes, Registrar of the Rochdale and Salford Courts was appointed Joint Registrar of the No 4 County Courts, which included the Lancaster, Preston, Blackburn, Chorley, Darwen and Blackpool courts, so the name Desquesnes once more became associated with Blackpool.

Sources;-

Newspaper archives

Wikipedia

Census returns, electoral rolls rates books

Denys Barber and the Friends of Layton Cemetery.

Websites;-

https://archive.org/stream/lancashirebiogra00lanc/lancashirebiogra00lanc_djvu.txt

https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Reform_of_Our_Land_Laws.html?id=Y5UCkAEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6460/1/FrenchLondonKellyCornick.pdf

http://http://www.worldwar1schoolarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ULULA_1917_10.pdf

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Desquesnes-5

JOEY NUTTALL

1869 Manchester – 1942 Blackpool

Swimming Champion of the World

The Stalybridge Phenomenon. The Lightning Merman

Joey Nuttall was born in Deansgate Manchester in 1869, and the family moved to Stalybridge soon after. The story of Joey’s swimming life and his exceptionally speedy rise from boy champion (he was included in a gala programme for the Tyldesley Club event for 1882) to adult amateur champion and then, as a working class hero to some, a professional, world champion, is well recorded. It was a time when professionalism was arising from the amateur ranks of sport and the working class sportsman of skill and opportunity could command high stakes and prize money. It was also a time when there was a moral distinction between the ethical purity of sport in the amateur ranks and the material and financial gains to be made in the professional arena which sullied that ethic of ‘sport for sports’ sake’. Even by 1902 it was regretted that the Prince of Wales could present a cup for an amateur race but the professionals, inspired by the ‘impurity’ of the gamblers, were denied that perceived honour due to their distance from that Victorian ethic. Of course the professional sportsman was always in danger of being the toy of their manager or backer. Even in the 1960’s it took a stand-off between a professional footballer, Blackpool’s home grown George Eastham, to take on the sports’ authorities to claim his rights. During the time that Joey was achieving both amateur and professional success, the amateur sport of swimming was going through changes promoted with vigour by the ASA secretary William Read of Blackpool (whose father had constructed the baths in the town) and continued in the same vein with his son Eric, a swimming and water polo blue of Cambridge. Joey had been English amateur swimming champion in 1886, 1887 and 1888 and from this last date he turned professional and continued his success.

Joey Nuttall’s personal life however is less well known and thus less well recorded. Stalybridge, where he grew up and began his swimming career, and where it is reported that the Huddersfield canal provided a good practice medium, had suffered the effects of the cotton famine caused by the American civil war and which affected the whole of Lancashire with both its extreme poverty and its consequent community solidarity in dealing with it. Joey’s eventual worldwide fame lit a beacon to this community and its working class of people in demonstrating that a person could break free from its restraints.

In 1881 11yr old Joseph was at school and living at 273 Garside’s Yard in Dukinfield, Stalybridge. He is living with his father Thomas, mother Betty, brothers George and William and sisters Georgina and Elizabeth. His father is a coal merchant. In 1891 Joey, at 21 had already been entitled the boy wonder and is classed as a Professor of Swimming in his job description. His mother has died and his father is now a beerhouse keeper at the Greyhound Inn, Hully St, Ashton under Lyne, Stalybridge where his two sisters, Georgina and Elizabeth Ann, work as waitresses, while his brother William carries on work as a coal merchant. It is reported that Joey eventually became landlord of the pub (1907-10) and the failure of the venture led to one of his financial crises.

From the opening of the public baths in Stalybridge, his prowess in swimming had developed, a skill which was quite intuitive to him and, turning professional by 1888 he was able to earn a reliable income. This income continued to support him until age caught up with him and he turned to exhibition swimming and swimming instruction, and managed a pub for a short time as other professional swimmers, including J A Jarvis whom he had trained, and who was a good friend, began to beat him. At the end of November 1901 he competed against his protégé Jarvis at the Manchester Osborne but lost by 3.35 seconds, Jarvis being the reluctant winner due to his respect for his teacher. They were both managed by Mr A Farrand of Leicester, a city where Joey spent much of his time and no doubt where he met his future wife Gertrude, who was a Leicester girl.

Billed as the Lightning Merman he performed at the Blackpool Tower aquatic show from the late 90’s which probably familiarised himself enough with the town to eventually return to live and work outside swimming which could no longer support him. In 1898 after his season at the Tower there was still opportunity for swimming challenges and he left for Loughborough with his managers to train for his forthcoming showdown with J McCusker, the American, at Hollingworth Lake, a mile race which Joey easily won. Joey was always more comfortable in still water though competed many times in sea races among which include those recorded at Brighton, Ipswich (the Ulph Cup), Plymouth and Llandudno. Blackpool also hosted swimming competitions in the sea. In 1901 a 500 yards swimming race was competed in the sea at Blackpool by the Blackpool club though Joey was not involved.

In the days of his amateur career it seems that his father acted as his manager. In one of his last amateur races in September of 1888 at Lambeth (which he easily won, breaking the record for the third year in succession) his father was present, looking after him. At this time Joey is described as ‘the most unassuming and friendly disposed of young fellows this or any other generation has known in connection with sport.’ At this time, a list of his amateur achievements which is claimed not to be comprehensive includes, ‘records for 40, 50, 80, 120, 160, 200, 300, 400, 440 (salt water), and 1,000 yards.’ In prizes these include ’25 and 15 guinea cups, £25 and £15.15s prizemoney, watches, 20 guinea diamond medal, 15 guinea silver fruit vase, 10 guinea gold medal, £25 challenge vase.’ Little wonder his dad looked after him. His physique is described as 5’ 5¾” in height and a little over ten stone in weight, and he won his first race, it is claimed, when nine years of age in the Stalybridge baths.

In 1893 September 13th Joey Nuttall set a world record time of 2mins 20 secs for 200 yards in the Accrington baths.

In 1901 Joey is boarding at 26 Fernally St in Hyde and is maintaining his profession as a swimmer. In this year he had been made the instructor at the Cossington Street baths in Leicester. By this time however, he was talking of retiring after his arranged race with J H Tyers when he had put out a challenge to any swimmer in the World to take him on for £300. He had already broken the world record for 300 yards in October of that year

Joey had tried to retire but it seemed that he wasn’t either very unlucky with finance or not very good with it. The income from exhibition swimming and instruction it appears, was insufficient to keep him and by 1901 he had fallen on hard times Such was the reputation of the quiet, unassuming champion admired by all in and out of the sport, one who glided through the water at great speed with hardly a ripple or a sound with his famous ‘Nuttall’ or ‘Lancashire’ kick of cross-legged and single, under arm stroke, and a champion who had challenged all worldwide and beaten all. Such a champion had earned the great respect and accolade of everyone and the swimming fraternity and influential well-wishers rallied to his side. Through testimonial galas and events, his financial poverty was alleviated. In this year the high profile Manchester Osborne club announced its intentions to support the idea of a benefit for Joey. In 1902 a benefit was held for him at the Leicester club (in which he swam and achieved the best time) though in this case, the financial return was disappointing. It was not unusual for a professional sportsman to be short of cash and in dire straits and Joey was not alone. While he had earlier a potential earning of £500 for a single competition, with the gamblers raising the stakes and the prize money, it was reported that fellow competitor J B Johnson, a former champion of England was in need, and lying in hospital in Leeds without an income, and it was hoped that his fellow swimmers would rally round to help him out.

Perhaps this financial help had enabled him to travel and swim for an come and he is to be found racing, and winning, in New York in 1904, reluctant to retire and taking on the Americans in their home waters, a difficult task to do as the crawl rather than the single arm action of Joey’s was becoming the dominant and faster stroke.

He had married Gertrude (born 1883 in Leicester) about 1909 and they had a son George whom they were to lose tragically later in life. Joey still describes himself as a professional swimmer though by now well past his peak he concentrated more on exhibition work. He is living at 49 Walmsley Street Stalybridge.

By 1925 it was discovered that he had fallen on hard times once more and it seems he had never been a good businessman though was not considered to be at fault for these hard times, (another report states illness for his predicament). In Blackpool he moved from one address to another, according to the electoral rolls. In 1925 the ex-mayor of Hyde, Walter Fowden wrote to the Liverpool Football Echo to appeal for funds to assist Joey Nuttall who had fallen on these hard times after several of his business enterprises had failed. The appeal was to all those in the sporting world to support a former champion who’d given a great deal to sport, and whose name had been on everyone’s lips at one time. Mr Fowden had already provided Joey with enough funds to keep him from homelessness. A gala did take place in November of that year at Stalybridge for the ‘Joey Nuttall’ Testimonial Fund in which champion swimmers and the English water polo team captain took part in competition and exhibition. By 1926 it is reported that, assisted by a fund of £200, collected from several galas in the North West, Joey and his son are now ’on their feet’, Joey having found an appointment in London.

Once more the swimming world had rallied to his assistance and again his situation was eased. Later on ,in his residency in Blackpool, he would no doubt be able to appreciate the success of his Cheshire born and fellow townsperson, Lucy Morton who was the first female individual swimmer to achieve an Olympic gold medal, this being at Paris in 1924. Swimming techniques had changed and the single arm, ‘trudgeon’ side stroke of Joey’s had been overtaken by the crawl, and the famous ‘Nuttall kick’ had become redundant. The more ‘graceful’ breaststroke of Lucy Morton was considered more apt for a woman.

At the time of his son’s death in 1928, he was living at No 5 Cromwell Road Blackpool and working at Fielding’s brickworks. He was working near his son George at the clay pit when the tunnel into the clay collapsed on top of him. George was working with Robert Swarbrick who had managed to jump clear. His father, Joey, was working close by and immediately ran to his assistance but to no avail. It’s perhaps uncomfortable to understand that the clay which has constructed some of the Hoo Hill or Warbreck bricks which hold up some of the houses in the area has been responsible for the death of a workman. There was a clay pit, a brick croft, where the school now stands on Warbreck Hill Road which in later years had naturally filled in with water to create a pond and was given the name locally of ‘Danger Deep’. Perhaps in understanding George’s death, it was not through some arcane and mystic, Celtic mythology of water, nor even the ever present danger of drowning to ward off carefree and adventurous youngsters that gave the body of water its name but a distantly obscured memory of the tragic death of a friend and neighbour, the son of the former, unbeatable swimming champion of the world.

In 1937 he reportedly made a final, celebrity appearance at Stalybridge baths, swimming two 25 yard lengths in good time for a 68 year old.

By 1939 Joey had retired, describing himself as a ‘general labourer retired’, and was living at 47 Calder Road, sharing the address with another family in the North Shore area of the town. Here, they have another child, a daughter, born about 1925, who is ‘at school’ and who later marries to become Mrs W Bailey (ref; Keith Myerscough). Joey would be 70 by now and Gertrude 56 years of age so they would have had their second child quite late and who would have been close to leaving school at that date.

Joey had a nephew, named after him and who also took up his uncle’s sport.

As a sportsman he was also interested in other sports. In 1899 he was a spectator at a running race in Oldham (it is reported that he lived in Oldham at some time) between Harper and Downer, two prominent names in athletics. In Blackpool there was ‘a dozen of promising runners going through their paces in anticipation of a match or a handicap at one of the centres’. Tom Burrows, another athlete with racing and jumping records also thought it suitable to make his home in Blackpool for training.

Joey’s death is recorded in 1942 and he is buried in Layton Cemetery Blackpool and, lacking funds for a gravestone at the time it seems, his plot is unmarked. A gravestone has been speculated for the cemetery at Layton, subject to funding it seems.

Update; A blue plaque projected for the site of the demolished Stalybridge baths (now a Tesco) was unveiled in September 2019 by Joey’s grandson, George Bailey at Stalybridge library.

Sources and further reading.

- Contemporary newspapers (via Findmypast).

Census returns, electoral rolls, bmd’s.

Wikipedia

Denys Barber and the Friends of Layton Cemetery.

Information taken from the following websites and not corroborated in the newspaper reports has been qualified with ‘reported’ or ‘stated’.

https://www.stalybridgecorrespondent.co.uk/tag/joey-nuttall-stalybridge/

https://www.blackpoolgazette.co.uk/news/lightning-merman-joey-1-389510

https;www.playingposts.co.uk/podcasts/joeynuttalthe- lightning-merman-of-stalybridge

THE READS WILLIAM, ENOCH, JOHN, JONATHAN, WILLIAM and ERIC.

THE READS WILLIAM, ENOCH,

JOHN, JONATHAN, WILLIAM and ERIC

4 generations of the Read name that lives on in Reads Avenue in the town as a relict of the Reads estates and reference to the gravestone in Layton Cemetery.

William Read, who originally brought the Read name to Blackpool, was born in Blackburn in 1806 and, by the time he began work as a weaver, he was living in Worsthorne, near Burnley. In 1826 he married Jane Baldwin at St Peters’ Church, Burnley and they began a family. Sometime in the 1830’s, William left his job at the mill and branched out on his own as a travelling salesman, quite a precarious thing to do. Perhaps unemployment had been forced upon him or perhaps he had confidence in his own ability, a confidence that was eventually proven as he created his own wealth and success. He was responsible for building both Reads Baths and Market situated on South Beach.

In the early days as a travelling salesman, and often with the help of his two young sons, John and Enoch, he pushed the cart containing the pots which he had chosen as his product, up and down the steep terrain of east Lancashire, moving from village to village. Hard work, especially in winter.

One of the towns he came to was Blackpool, and sometime in the late 1840’s he decided to settle down and he took up the rent of a stall in the market. Blackpool had a large watershed of customers especially in the summer season. The arrival of the trains in 1846, made sure that these numerous customers would come to him, and it was probably the major influence of his decision to settle in the town. His customers would now come to him rather than it was he who had to go out in search of his customers. He was evidently a capable salesman and hard worker and from these small beginnings he never looked back, bringing his family to live in the town. The women in his family don’t get much of a mention in the records, and Jane must have worked hard also to keep the family together. He was one to speculate, and Blackpool was the right place to do that at the beginning of the property boom years with land prices increasing and farms and much of the vacant land giving way to development. On his death, William left, in part of his will, £400 to his children in equal amounts of £50, so it’s reasonable to assume that he and Jane had eight living children in total.

Three sons, John, Enoch and Jonathan, continued the family success through the next generation. A son William was born on the 17th February 1834 in Worsthorne, though he doesn’t appear to have had the successes of his brothers and I’ve not been able to determine a date of death for him.

Enoch Read was born on March 14th 1836 at Worsthorne while his father was working as a weaver. He was baptised on May 11th at Keighley Green Methodist church. In 1860 he was living in Preston where he was working as a general dealer. In late December of that year, he married Ellen Elliot at the Parish Church Preston. Both are described as ‘of this town’ in the bmd section of the Preston Advertiser. Enoch is living in Clayton Court.

By the 1861 census Enoch, as head of household, is a general dealer aged 25 and living in Duddeston Rd, Aston, Birmingham. His wife Ellen is not at the address but his brother John (11 years older than Enoch) and his father William are all described as general dealers. Also John’s wife, Sarah is at the address and is not given any status.

Enoch’s business activities expand and by June 1866, and resident at 50 (possibly a misprint as the census gives his address as no 53) Howe Street Birmingham he is advertising his consignment of Alderney and Guernsey cows for sale.

By the 1871 census, Enoch is living with his wife Ellen and their two year old son Enoch. Enoch senior is now a potato dealer and employs three men at 53 Howe Street Aston, Birmingham. His nephew, William H is living with him and working as a carter.

In 1872, Enoch is in dispute with the Local Board in Blackpool about rates payable on land and buildings arising from the construction of the new promenade (opened with great ceremony in 1870).

In June of 1875 Enoch died in Birmingham and his body was brought back to Blackpool for burial at the Bethesda Chapel. His obituary in the Bedfordshire Mercury of June 19th reveals that he was the second son of William Read, a hawker of pots. Even at 10 years old he and his brother used to help his father push the cartload of pots from town to town from their home town of Worsthorne near Burnley. Eventually they settled in Blackpool and William took a stall at the current market which was about 1845 and, so the article goes on to say, through sheer hard work and honest effort, reaped the rewards of success.

Not long after, in August of 1875, Enoch’s wife Ellen died at Kent Road in the town. She was 36 years old.

Enoch’s opportunity for wealth arose when there was a hay famine in the north of England and he bought up extensive supplies of hay from the South of the country and sold them in the north, making a pretty penny out of it. In doing so he became the largest dealer in England and traded internationally too, in Europe. He also dealt with cattle, importing them and selling them on at auction.

But he had the closest attachment to Blackpool, where he had his first success in learning from the industry of his father. He owned land in many counties and in Blackpool his estate already included Reads Road (now Reads Avenue) along which many houses of quality had been built because he wanted Blackpool to be a quality place to live and visit. He was preparing to move back, and his prospective house had been built and the furnishings had been finished and all was ready for the move.

His body was carried back to Blackpool on the 2nd June. He was a well respected man and at his funeral there were 100 tradesmen along with many Blackpool residents and gentlemen from Birmingham. The Reverend Waymanconducted the service at the Victoria Street chapel before the coffin proceeded to the Bethesda Chapel for burial. Conducting his eulogy in the chapel graveyard, the Rev Wayman described Enoch as a man who had come from nothing but who had not forgotten his roots. He had done much to open up Blackpool and when the story of Blackpool would be told, he would be ‘counted amongst its earliest benefactors’.

In October of1875, the executors of Enoch’s estate continued its development in advertising for contractors to create roads through Bonny’s estate in respect of the late Enoch Read.

However, there was a prolonged dispute over Enoch’s. As Enoch’s body had been brought back from Birmingham, there was a deep division within some members of the family. One member of the family had made an application to the Home secretary to have the body removed from its resting place at Bethesda Chapel to be buried elsewhere. Such was the intensity of the rift that, when it was discovered that the ground around the vault had been disturbed, it was feared that the body had been removed by the other party. This encouraged the trustees of the Chapel to investigate and in doing so found the body to be still in place. However, they decided to take action against the perpetrator, whoever this may have been.

In 1876the distribution ofEnoch Read’s estate is challenged in a case Read v Read. John and Jonathan are described as two of the defendants.

In 1877more of Enoch’s estate is sold off but the reason being in this case is that he has given up farming (which he most certainly had done!). It is Hunters Pool Farm at Mottram St Andrew in Cheshire and included all the farming equipment and livestock.

In August of 1878Enoch’s estate is still being sold off within the conditions of the case Read v Read. Enoch had owned several properties throughout the country and this case concerned his estate in Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire.

In 1898more ofthe estate of the ‘late Enoch Read’ was eventually sold off in 16 plots of building land. This included some on Read’s Road and some frontage to Whitegate Lane. This land is referred to as William Read’s estate. No 2 Cocker Street, (called Rowland House and the auction announcement makes no mention of the baths), and which sold for £3,666, the Belvedere hotel which sold for £2,500 on the promenade at Central Beach. Land was bought by anybody with any money for development in the boom times of the town.

Finally, in 1900 the residue of Enoch’s estate was old off by the trustees. It included land fronting Whitegate lane and Palatine Road and numbers 18 and 20 Nelson Terrace on Revoe Road.

John Read

In August 1888 John Read died at 30 Bonny Street. He had been ill for about a year and was 60 years of age, suffering from bronchitis and jaundice at the time of his death. He was born in Worsthorne in 1828 and along with his father and brother Enoch, helped his father in hawking pots until the family eventually settled in Blackpool. John went into the potato trade with his brother Enoch and lived in Birmingham for some time, especially during the winters for some reason. Like his brothers he speculated in property and prospered through it. For some time he had a home address on Park Road before moving to number 30 Bonny Street. He left his whole estate to his wife and on her death it would pass to his only son Alfred. At his funeral were several councillors and property owners and he had taken an active interest in the town’s affairs (his nephew William John would marry the daughter of Councillor Fish). He was a trustee of his brother, Enoch’s, estate. He was a Weselyan as defined religiously.

In 1866John and Jonathan Read sold off land in three lots at auction including tenanted properties in Cocker Street, King Street, Church Street and High street.

In 1868both John and Jonathan Read sold off more land and property in King Street, High Street, Cocker Street, some for building and some as tenanted properties. In 1871John Read is living at No 30 Bonny Street which is next door to the Brunswick Hotel and he is a potato merchant. He is living with his wife, Sarah.

In1891Alfred Read, son of John Read, is living ay No 57 Albert Street with his wife Elizabeth and children John and Florrie who are at school. Alfred is a house and land estate agent.

In 1939 Arthur Read, John’s son and Eric’s cousin is a provision merchants’ representative and his wife Margaret is a hotel proprietress.

Jonathan

Jonathan was born in Worsthorne in 1841. He is perhaps the most prominent of the brothers in the direct affairs of Blackpool. Proprietor of the Baths and Market on the sea front, Chairman of the Raikes Hall, Councillor for Brunswick Ward, though he didn’t always get on with the Local Board, being served with notices for fly tipping in 1875 and fined 5s (25p) for letting his dogs run amok on Bonny’s estate in 1882 (though by now, shortly before his death, he would have been vey poorly).

He is first in the records in 1863.While correcting some information concerning the origins of the (north) pier construction, James Rigby, architect and surveyor of Preston, suggested that the original idea was put to him by a Mr Lewis and while he himself had been supervising the construction of two houses on South Beach belonging to the late John Cragg, he had just completed the New Market and Baths and Assembly Rooms for Mr Read, and had little time to take up in sketching designs for the new pier.

In 1866John and Jonathan Read sold off land in three lots at auction including tenanted properties in Cocker Street, King Street, Church Street and High street.

In 1868both John and Jonathan Read sold off land and property in King Street, High Street, Cocker Street, some as building and some as tenanted properties.

On the 1871 census Jonathan and his wife Emma are living at 20 South Beach. The two elder daughters are born in Smethwick and the youngest daughter, 5 year old Emma is born in Blackpool. John is a potato merchant and baths proprietor.

Later in the year, in June of 1871, Jonathan Read and two business partners dissolved their partnership of hay and straw dealing.

In 1875 Jonathan Read along with William Bailey,’ both of who are declining the farming business’ sells up all his farming equipment and livestock.

In August 1879 the well-known, well-established and well-stocked Reads Market on the South Beach frontage, set alight. A little before 6am the first anyone knew of it was the ringing of the fire bell in Back Victoria Street. Though the fire brigade was quickly at the scene, there was little hope of saving any of the stock, much of which was either part insured or uninsured by the individual stallholders. They instead concentrated in containing the fire to stop it from spreading to the neighbouring premises, on the one side the house of the owner, Jonathan Read and on the other, the house of Thomas Heap on Bonny St. which had suffered a little damage. The single storey market building was completely gutted and the nature of the goods within it, consisting of drapery, wooden toys, dolls, clothing and a large collection of books. Most stallholders suffered some loss, and some complete, devastating loss. Several stalls of jewellery were lost and Mary Whalley, whose stalls ran the complete length of one side, lost at least £1,000. Mr Howarth who had insured his book stall for £750 had let the insurance lapse. He also lost £50 in gold which he had intended to take to the bank, but had put under one of his stalls instead. It was hoped that the gold would eventually be recovered in the debris. At the outbreak of the fire, Jonathan Read with ‘characteristic energy’ gave every assistance.

On the 1881 Census Jonathan Read, living at No 20 South Beach is a farmer of 30 acres employing one man and he is also a baths proprietor. He is 40 years old and is also a Councillor. His wife is Ann and his only child is John William, 19 years old, an articled solicitor’s clerk (born in Smethwick). Also at the address, are Sarah Squires and a niece, Emma. There is a niece living next door too.

In 1882,on the 22 January Jonathan Read, proprietor of the large baths in Blackpool died of heart disease at his home at No 20 South Beach. Avery popular man, at his funeral the cortege was several hundred yards long and all walks of life were represented, from civics to tradesmen. Six coaches conveyed family members. All the eight pallbearers were tenants of the Read’s estate. At the house, a short service was conducted by the Rev Mallilieu, Primitive Methodist, and at the cemetery it was conducted by Rev J M Pilter at the Non-Conformist Chapel. There had been some controversy over the Council status of Jonathan Read and there had been rumours circulating of corruption, though non-corroborated, in Council circles. In November of the previous year, a petition ad been lodged with the Town Clerk, objecting to the potential re-election of Jonathan as Councillor for the Brunswick Ward in the town. Jonathan was a Liberal candidate and the claims of bribery and corruption true or false (he was a popular man and so any opposition would have been a daring thing to do) were no doubt made by rival politicians within the Whig and Tory rivalry of that episode of British politics. The petition for the hearing of the complaint was about to be heard on the 23rd of February before a commissioner of the High Court, so it was no mean complaint and, by then, Jonathan had died.

The Conservatives won the election. Hmnn. But earlier Mrs Read had thanked the Council by letter for the vote of condolence on her husband’s death, so a protocol had been maintained with the Council chamber.

In 1891, William John Read (son of Jonathan ) 29 years old is now a solicitor in his own right and is residing at 2 Cocker Street (the swimming baths) of which Emma Squires, 40 years old, is the proprietress. Also visiting the address is Frederick Grime, the newspaper editor.

In September 1892 Reads North Shore Baths was up at auction. An attractive option for a potential buyer, it was situated in the ‘flourishing’ watering place which attracts over a million visitors from all part of the United Kingdom.’ The main swimming bath was 52’3” long by 23’9” wide (16m x 7m approx.) and there was as a small swimming bath for women and children. Both salt and freshwater baths with vapour and shower baths were available. There is a gallery which runs around the main bath for use at swimming galas. The solicitor in charge of selling the baths is William J Read of 6 Lytham St, the late Jonathan’s son. William himself went on to create the South Shore Open Air Baths.

In 1893 on the 11th March, Manchester, William John Read, only son of (the late) Councillor Jonathan Read marries Clara Fish, third daughter of Councillor James Fish.

On September 5th 1895 Eric is born to William and Clara. He was baptised on the 5th April 1896. William is a solicitor and their home address is Fairholme, Park Road Blackpool.

In 1901 William Read, a solicitor, and wife Clara and family are living at 64 Withnell Rd. Daughters here, are Gladys, Hilda and Dorothy. Eric is the only son.

In 1906Eric is at Arnold House School and his father’s address is 134 Whitegate Drive. He leaves in July of 1910 to study law at the Leys School, Cambridge. He took his exams after the War in which he had enlisted in the RFA.

In1911William and Clara are living at No2 Liverpool Road. Daughters, Gladys Hilary and Dorothy are still at home. Eric is studying at Cambridge.

On the 13th April1918William Read learnt tha this son Eric Read had been wounded and was recuperating in the base hospital. Capt Read had gone out with Colonel Topping with the West Lancashire Brigade and had recently been awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre.

On the 1922 electoral rolls, Eric Readis living at 35 Raikes Parade with parents Clara and William John and at an address in Lomond Ave on the 1939 register with wife Oriana.

In 1929 Eric was appointed vice chairmen of the Northern Counties Amateur Swimming Association. He had won his Cambridge half blue at both swimming and water polo. His father was also well known in swimming circles as he had been associated with the sport for many years.

In 1930 Eric and his wife Oriana were registered to vote in the Brunswick Ward at No 32 Birley Street, their home address being ‘Pinfold’ Lomond Avenue.

On Armistice Day 1930Eric Read objected to the suggestion from one of the Blackpool clergy that the military should not be represented at the cenotaph. War will always be conducted but at the same time will always be controversial. Eric Read had seen the War first hand and he refers to the current trouble in India and the Middle East and is fearful that it all might happen again. It did, of course, and it still does. The general theme of the clergy was that National pride might be cementing for one nation but conflicting with another and the result is war. The modern theme represented by the poppy reflects both points of view that all humans suffering in War are themselves a poppy and it is not a reflection merely of National pride, which can create the conditions of war if not properly exercised. The sacrifice of life should not be usurped by those who are afflicted by an extreme and introverted patriotism for self-assertive or political ends.

In 1931Major Eric Read was the Commanding Officer of the Blackpool Battery (the 351st Field Battery of the 88th Brigade of the Royal Artillery Territorial Army). Their headquarters were the Yorkshire Street drill hall. At this time the battery was only seven men under strength, numbering five officers and 74 other ranks. In 1939 during the conscription drive it is recorded in a newspaper article that Eric Read was in possession of a book which recorded the information on the formation of the Blackpool volunteers and the origin of the battery. County volunteer groups had first been organised as the fear of a French invasion grew, to deliver the country ‘from all the Miseries and Horrors which would otherwise arise from the Landing of an Enemy.’ Many volunteer groups came to the Fylde coast to train and the first observation from an aircraft with information successfully brought back to headquarters was exercised on one of these practices prior to WW1. In Blackpool, the book in possession of Eric Read shows that the first volunteer to join up on June 1st 1865 was 28 year old Thomas Swarbrick, a bookseller who lived at South Beach and was 5’7” tall. Other names that signed up at the time were 20 year old William Barrett, a publican at the Victoria Hotel and 5’7¾” tall. Then there was David Rae, 22 years old and an auctioneer of Lytham Street; Peter White 30 years old and 5’9” who was a builder of Cookson Street; George Marsh, 5’10”, a stonemason of the Schoolhouse, South Shore and William Griffiths, an artist of Larkhill who was 34 years old and 5’9” in height.

Other notable names which joined the Volunteers at one time or another are John Bickerstaffe of the Wellington Hotel and 25 years old at the time, later to be mayor and receive a knighthood, and Jacob Parkinson, at 39 years old, a joiner whose business would rise to international acclaim under the direction of his son, Lindsay, who was another Blackpool pioneer and also a future mayor in the WW1 war years and who was also later to be knighted.

The first action of the battery was at Mount Kemmel in 1916 when the battery had been given the moniker of the Topping Boys after their Commander in Chief, Major Topping. It had gone to France in 1915 as the 11th Battery of the 2nd West Lancashire Brigade but when it went into action in 1916 it had been designated as 276th Battery

In 1931 Eric becomes the president of the NCASA (Northern Counties Amateur Swimming Association) on the retirement of the current chairman Mr Alec Charters.

In 1932 Major Read took the salute at the gathering of ex-servicemen in Blackpool. Among those present who paraded along the Promenade to the haunting renditions of Tipperary in the pouring rain from the central Pier to the Cenotaph, were those soldiers representing nearly every British army campaign of the previous 50 years, a Croix de Guerre, Romanian VC and the Boer War. Among those were Mr H Hampton who won his DCM at Rourke’s Drift in 1881 and was one of the very few survivors of that battle. The soldiers then went for tea at the Winter Gardens and then were given a tour of the Illuminations afterwards.

On 27/3/1937William John Read died at his home. He had been immobilised by severe rheumatism. He was 75 years of age and had planned to spend a long holiday with his married daughter in Whitstable.

He was the principle member of the Reads firm of Blackpool solicitors of which his son, Major Eric Read was the senior practicing solicitor. Well known in Blackpool circles with his interest in swimming and life-saving, he was influential in the building of the famous Open Air Baths in South Shore. He was honorary solicitor of the Amateur Swimming Association a national organisation from 1895 to 1938. He was also chief official for the Northern Counties Swimming and Water Polo Organisation for many years. The creation of the Northern Counties Swimming Association came about after conflict between the regional status of competitors conflicted with that of the rules governed by London. This resulted, under the strong influence of William Read, in a regional division of groups consisting of North, South and Midlands. William kept up his interest in the sport until his dying day. For thirty years he had been restricted by severe rheumatism and attended meetings in an invalid carriage. He was present at the first National swimming meeting held at the new South Shore Open Air Baths in 1935, a building in which he had a great influence within the Council in its construction.

In 1939 Eric was living with his wife Oriana and daughters June and Elizabeth at Pinfold in Poulton le Fylde. Eric is an ARP driver and Oriana is in the WVS. The daughters are at school. He is currently the honorary solicitor of the Amateur Swimming Association.

In 1939 Clara Read, widowed is living with her daughters Hilda and Dorothy at No 80 West Park Drive. Hilda is a teacher of singing and Dorothy is working in the WVS as a hospital cook.

On the 25 March1940the will of Clara Read is pubished. She leaves part of her estate to her son Eric and daughters Gladys, Hilda and Dorothy and a money bequeath to her daughter-in-law, Oriana Dickson Read. The home address is 80 West Park Drive. On the 1939 register Dorothy is in the WVS as a cook at the Hospital.

In August of 1940when football had ceased at Bloomfield Road as the RAF had taken over the ground, manager Joe Smith was out of a job. Eric Read, being a keen sportsman and a Cambridge Blue, and a member of the Blackpool bench considering licensing application, had successfully put forward the name of the manager, renowned in footballing circles, as the new manager of the County Hotel. Thus in August 1940, Joe Smith was Blackpool’s newest licensee.

In November 1940 Major Eric Read was re-elected as honorary secretary to the Fylde District Law Society for the 15th time and like his father, was made an honorary life member. The Read name had a 48 year history of membership to the society.

In 1944 Colonel Eric Read as Commander of the Home Guard (the H G’s) presented a certificate for meritorious and good service to Company Sergeant Major Thomas Henry Williamson of 45 Sunningdale Avenue, Marton. He is managing director of Messrs C W Whitehead Ltd of Preston. He had served in India as a troop instructor during WW1.

Eric Read dies in 1975, and the family continues from there.

Sources

All material has come from the newspaper archives, the bmd records and the census returns. The photograph of the march past at Stanley Park is sourced beneath.