George Washington Williams 1849-1891

Soldier, preacher, politician, lawyer, historian, traveller, public speaker, lecturer, champion of his race and stern critic of the established inertia towards the resolution of worldwide slavery, especially within the American and African continents.

Born in Pennsylvania USA in 1849 and died in Blackpool, UK 1891. Buried in Layton Cemetery in the town.

Forward

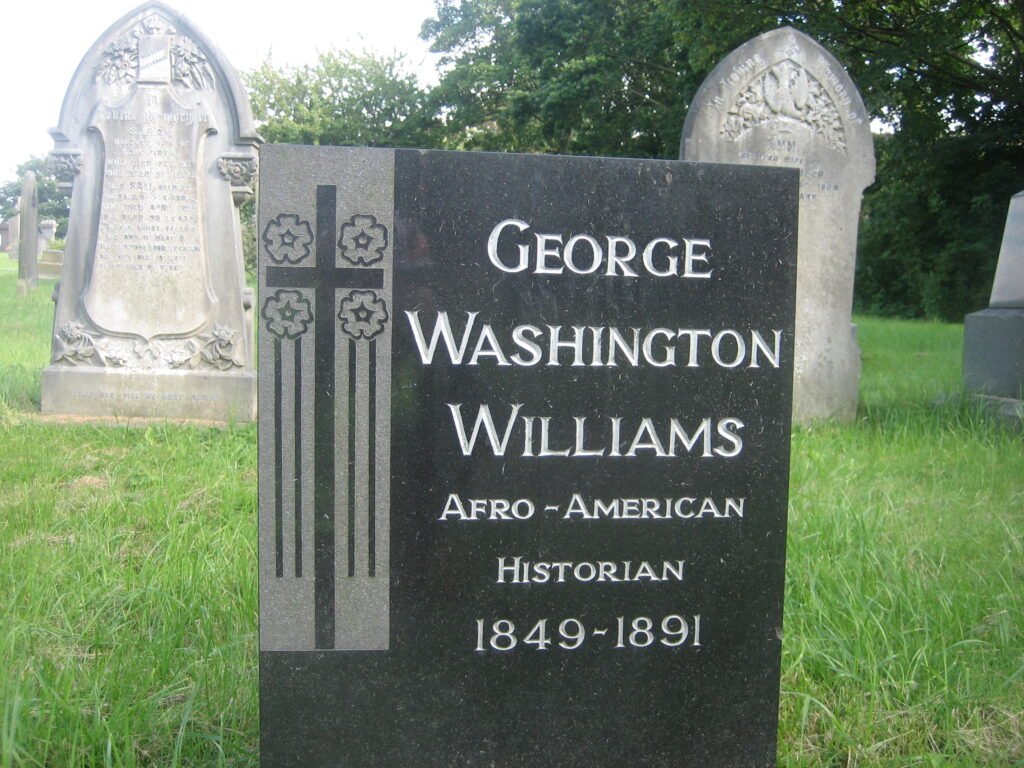

In 1975 a small group of people made a pilgrimage to a grave site identified as Section F, grave number 123 in Blackpool’s Layton Cemetery. They were escorted by the cemetery warden, and included two photographers, a reporter, Blackpool director of attractions and publicity Alan Bryant, and the deceased subject’s biographer, American lecturer John Hope Franklin and his wife. For his biographer, the purpose of the occasion was to include, as a significant part of his visit to Blackpool, the laying of a wreath on the then unmarked grave of his subject, George Washington Williams. As far back as 1945, professor and teacher, John Hope Franklin had at first come across his subject’s, ‘A History of the Negro Race in America From 1619-1880’ published in 1882 and his earlier work published in 1881, entitled, ‘A History of Negro Troops in the War of Rebellion 1861-65.’ Fascinated by the significance of these publications, he had spent the intervening years from 1945 to this day in 1975, assiduously tracking down, like an archaeologist or palaeontologist with a pointing trowel, his subject’s somewhat unique, adventurous and trailblazing, short life story and his subsequent biography is largely the reason why the story of George Washington Williams is available to all today.

From that time, and by 1986 when John Hope Franklin was ready to publish his volume on George Washington Williams, instead of a bare patch of ground identified by a location number only, there was a shiny black granite headstone, with its relevant inscription, and to this day it is there to view.

George Washington Williams, in his natural status of black Afro-American, with a mix of white within him, was born to a freed slave in Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania on October 16th 1849 and he died of TB, after an eventful short, but dramatic life, far away in Blackpool UK on August 2nd 1891. He was a first of his kind in many ways as he had found fame, and sometimes notoriety in the opinion of some variously , as pastor, statesman, lawyer, historian, soldier and traveller, and one of those people who, it might be said, in a popular idiom, to have been born too soon when the world wasn’t ready for them.

From his modest, semi-literate beginnings he had risen to talk with kings and presidents, worked closely with a future president, gained a degree and become ordained as a Baptist minister. He had also risen to take on established states and kingdoms in the world of politics to champion the clear sense of injustice he saw before him, not only with his precise command of language and effective, personal presentation, but also, even before adulthood, he had set off on his life’s adventure with the gun as he joined the Union army during the Civil War. Shortly before the end of his life he had travelled through Africa in the footsteps of Henry Stanley but with a very different remit. He considered all kinds of justice, not just that denied the race he was born into but, ultimately, in the tireless pursuit of his ambitions, everything was at the cost of being able to live a normal, simple life.

The high sounding resonance of his name reflects an association with the former slavery of the American continent. Though George was born free, his father, Thomas Williams had been born into slavery, but was a free man on the birth of his son George. While his surname would be that of the plantation owner, ‘George Washington’ was one of those impersonal and popular names which could easily be referred to and equally easily be remembered, slaves of all the eras of human history in all areas of the world being mere pieces of property. How Thomas came to give his son that name is unknown but it seems to have been freely given.

‘Black’ and ‘white’ and ‘negro’ are used as George’s (black) biographer, John Hope Franklin uses them. ‘Afro-American’ is also used but this is becoming outdated as it suggests ethnicities outside people of the same culture as both Afro-Americans and Afro-Europeans are several generations into the same cultural background and expression, as to be different only as much as all humans differ by being tall or small, fat or thin, male, female as the contemporary gender norms.

George’s somewhat highly sensitive and explorative mind had, from its birth, been thrown into a life of chaos around him and it created its own chaos within him at times. When George was still very young, his father had fallen into bad company and, preferred drink to the responsibilities of marriage and children. George’s parents split up and her son George became unruly in his frustration and spent some early adolescent days in a house of refuge. Thomas Williams did return later on in reconciliation but this was too late for his son, George, whose intellectually energetic body and spirit, saddled with strong uncertainties and contradictions was evidently profoundly unsettled. There was so much unfairness around him which it appeared everyone had to accept hands down, but to which no-one could resolve or to which an answer could be given. While the subject of race was highly relevant to him however, there were rigidly divided differences and confrontations across the whole range of human experience.

George was intellectually demanding for the truth and the truth could only come from a struggle to find it. He would discover, while still young and perhaps from the house of refuge he had been admitted to, a description of truth and fairness in Christianity which was the readily available spiritual belief and which, in its construction, to him spoke more of fairness than anything else. His life then consisted of a heroic pursuit and championship of these truths, focussed in almost autistic manner, but his life also shared a conflict with his religion and his own declarations to his wife and family. And if money had to be borrowed, paying it back was secondary to the pursuit of his ambitions, and relationships with others could be more functional and practical rather than loyally committed. Eventually, after marrying, his family had to survive without him, since his ambitions took him away from home, sometimes far away, and sometimes for long periods. Without a divorce, he had become engaged to another woman during his life, if not in reality at least once, then more times by his detractors and opponents. If he was not a philanderer he was evidently comfortable in the company of women, as women most certainly appeared to be in his, and probably mostly at least, without a physical commitment, just a mutually encouraging need in the reflection of sexual status.

The fluidity of life experience was forever changing before him and his choice of political Republicanism was eventually questioned within himself. To dwell too much on the fact of his alleged marital infidelities and his very real financial debts would distract from the true character and purpose of the man, but in Middletown Ohio, where George was active in politics for a while, the local newspaper, the Argus had lots to say in sarcastic and derisive manner in representing its readership about such things when the flamboyant man had stayed in the town for a short time. A truth about George might perhaps be extracted from an interpretation of both sets of reports, Those that have taken a negative view of George would opt for the Middletown view, and those with perhaps a more sympathetic but necessarily objective and incisive view of George would refrain from this and hold their counsel, pointing rather to his strengths and contributions to history and the promotion of the status of his race, while all the while accepting his faults.

~~~~~~~

Thus with all these uncertainties and questions circling around his head like a swarm of flies, George grew up ‘wicked and wild’ and, as his mother was seemingly unable to control him, he was placed in a house of refuge for some time. It was here that he came across religious principles which gave some order and meaning to his life and it was here also that he first formed a practical and inquiring interest in the origin of his race in Africa. With all the frustrated and highly charged energies of a fourteen year old boy and a reason to legitimately unleash his energies in the cause of justice, the Civil War fever gripped him like many others and, after blacks were allowed to join up, he ran away to join the Union army to fight for that justice, as the North and freedom confronted the South and the injustice of slavery. Though only young, he passed as more mature as he was quite well built and he couldn’t joined up locally because he would have been recognised as underage, so leaving town was the only option. He also used an assumed name (tracked down by his biographer as either William or Charles Steward, or both), joining the Colored Regiment. He was present at several battles and understandably at the final sequence of battles at Petersburg which involved the largest concentration of negro troops. Having been wounded during this last engagement, he was discharged from the 41st infantry in 1865. From here he wasn’t yet done in fighting for the high ideals of a perception of justice and fairness, and he went to fight against Maximilian, a liberal minded yet puppet king of the European powers in Mexico, who had been confronted by the liberating army of former President Benito Suarez. Many Americans, buoyed up by their success in fighting for freedom in the Civil War which had now ended, joined up to fight for this liberating army, as America had demanded the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico who were supporting their own, convenient European regime on the American continent. While this confrontation was resolved by 1867, it seems that George then signed up to the 10th Cavalry until medically discharged the following year, perhaps as a result of the former gunshot wound to the lung, or perhaps, as John Hope Franklin sentimentalises, he just didn’t want to die just yet. Thus ended a short time as a Buffalo soldier, the race of immigrant African described as such by the race of indigenous American.

His next move from 1872-1874 was to satisfy his intellectual and spiritual energies and, as semi-illiterate, after a short spell at Howard University in Washington, a black college, he was accepted into the Newton Theological Institution in Massachusetts, close to Boston. Such were his evident capabilities that he had soon caught up with the other students who had come from established, educated backgrounds. On graduation he was the first colored man to do so from the college. The graduation ceremony for the 25 or so students took place on June 10th 1874, George’s thesis being the ‘Early Church in Africa’ and his address given as Newcastle, Pennsylvania. From here, out of his rough beginnings, he had become a refined gentleman with an infectious manner and a fine turn of phrase which would eventually turn many an eye and an ear towards him and which would confuse his critics who would have to look elsewhere for his faults. In nearby Boston he involved himself in the black community and by 1873, while still a student, he was elected as pastor of the Twelfth Baptist Church in the city, a position that would give him $50 a month stipend. ($50; $1 317.64; 2023).

By 1874 he had married Sarah but his natural emotional and physical expression in the communion of another human being was perhaps only a temporary and occasional focus and, in the greater scheme of things in the pursuit of his intellectual drive, he saw himself as a politician and put himself forward as a candidate for the Massachusetts Legislature. But he wasn’t finished there, as the only black newspaper of any influence, the New National Era, had recently folded and he saw the importance of giving the black community a sympathetic voice, so he founded the ‘Commoner’, as editor, columnist, reporter and publisher, resigning from his pastorate in Boston in order to put his energies into the newspaper. He had toured extensively in the South, in the wake of black injustices and massacres, giving lectures and to seek the support of interest in the newspaper and to attract financial backers but there were few subscribers, and promises of money would not be not forthcoming. He was also not entirely popular with many of the black people since his style was too sophisticated and thus remote from the bulk of the community. He wouldn’t compromise however and his paper foundered after only six months, leaving him and his few backers in debt.

By 1875 he was in Cincinnati as a preacher using his energies in an attempt to organise the churches to consolidate for financial security, but was resisted as each church wanted its own, local identity. In 1876, still feeling the importance of maintaining a presence in the newspapers, he became a regular contributor to the ‘Commercial’ (as nom de plume ‘Aristides’, no doubt a name chosen to reflect his own sense of injustice in the world) in Cincinnati. In this capacity he became the first black, newspaper columnist.

An interesting story in November of 1877 in Cincinnati is that a George Washington Williams married Sarah Walker. John Hope Franklin has her name as Sarah Sterret, and her name is accepted as that but, in a Cincinnati newspaper report, perhaps coincidentally, a George Washington Williams marries a Sarah Walker. If this is the same George and Sarah, then in the rather critical article in the Cincinnati Daily Times, it does reveal the obtuse contempt that one human being can show to another when George applied for a licence to marry Sarah Walker. The fee was $1, but ‘some wags’ at the courthouse advised him that he could get the fee reduced to 50 cents. So here, George is incorrectly described as ‘from the sunny south’ and ‘as black as the Ace of spades’ and Sally is either ‘strictly ebony or a mulateress’, the paper didn’t care to define. To watch his bartering in front of them in the courthouse was a bit of fun encouraged by those ‘wags’ who sat back to have a laugh at the proceedings as George attempted to get the fee reduced. (Cincinnati Daily Times Nov 9 1877.) Perhaps if this does refer to George, then they might have already been aware that the swagger in his claim to wealth through his expensive clothes and jewellery, actually concealed the borrowing of unpaid debts. It is not known whether this George was able to get the fee reduced, but if it was the real George then he would have very likely succeeded.

While in Cincinnati he preached a sense of world order as perceived through the religious concept of Christianity which had led him into the world of politics, and he continued to stand up for the blacks against the continuing violence in the South. What seemed simple to George in principle was in fact in politics, a complex web of divided opinion, self-interest and opportunity exercised by both black and white, but his character was equal to it all and his singular focus was both his strength and his Achilles heel. His lack of ultimate success was perhaps due to his dearth of material means and being black was a disadvantage, often in the face of those who were perhaps not as intellectual or clever as he was. He was a survivor with his own qualities and with his command of strong and eloquent language, he became a spokesman for the Negro Republicans. Republicanism, in name at least was what had been fought for in the Civil War and at that time represented freedom. John Hope Franklin writing a hundred years later though, thought that the status of the black person in the Republican administration of Ronald Reagan had diminished. (Courier News, Blytheville, (Ark.)-Wednesday, June 25, 1986). Such is the painful unpredictability of progress.

Perhaps his baptism into politics had opened his eyes to its intricate mechanisms and he was able to study law in 1877 under Alphonso Taft, US Attorney and politician in Cincinnati and father of the future President William Howard Taft (1909-13). He was also given a job by Alphonso Taft on the Cincinnati railroad in the office as white collar worker, though it was a railroad that had its objectors in its controversy. He continued to campaign for the Republicans and they won the 1878 election. His law studies would eventually see him admitted to the Bar in 1881.

Though ultimately he felt that the Republicans were just using him to get black votes for them with no intention of offering him a situation with a salary, and he had a young family to support by now, he continued where he considered he could pursue and promote his principles and personal ambitions. In 1879 he was nominated for the Hamilton County Republican party and he put his honest energies into the campaign trail, speaking in many towns along the way and, not content with doing just one thing only, it was while he was writing his ‘History of the Negro Race’. Elected in June 1880 as the Republican Party won the 1880 presidential election after much political wrangling, he served in the Ohio Legislature first becoming active in putting forward a bill opposing the objections to miscegenation – inter racial marriage – which he succeeded in getting passed in the State. Throughout his term he was able to keep influential friends who financed him, but for which the black community could legitimately doubt him. Even as a member of the Legislature however, he was at one time refused service in a restaurant as a black person and he succeeded in censuring and convicting the owner. As the Hon George Washington Williams, he had brought the case to the House, that the House should condemn racial discrimination.

He continued in office, putting his energies into campaigning for better conditions, pensions and compensations for war veterans (which would refer to himself, too) and which included both the Mexican and Civil Wars. The Mexican war being that of 1848 when much of the Hispanic south of North America was ceded to the US or bought for a price. As chairman of the Committee of the State Library he also campaigned for better pay for the top level library workers and he proposed anti-liquor laws, perhaps being intimately influenced by his own negative experience with his father and his own commitment to Christianity.

While in the Legislature he also put his tireless energies into a scheme to help blacks migrate away from the unsympathetic South. There was general interest in this idea and on the surface it was a legitimate proposal. Some land proposed for blacks for just this purpose in New Mexico consisted of 700,000 productive acres but, when George made a visit to investigate, he found only 51,000 acres of the harshest terrain which would be of no use at all. So in discovering this he had saved many thousands of hopeful migrants from undertaking a useless and indeed heart breaking journey. New Mexico wasn’t part of the Union until included in 1912 along with Arizona during William Taft’s presidency. To offer blacks an opportunity to move from the South would have been both genuinely convenient for some to move them out of the Union yet genuinely philanthropic for others, who might have been ignorant of the condition of the land. The South was still anti-black –education and opportunity were denied and even being free for any worker was virtual slavery. It was evident that the 1875 Civil Rights Act was not being implemented or enforced and in this respect, a Negro convention in Louisville was arranged to explore how to improve the situation for the Negro and to prevent discrimination.

In his single mindedness however, George was able to succeed in alienating both white and black and found himself compromised by his need to fulfil his personal ambitions for which he needed finance. On the proposal to close down the black Avondale cemetery in Cincinnati, when no more black burials were to be allowed because the cemetery was now considered a nuisance, he lost many black supporters over his reluctance to actively counter the closure. The cemetery in question was unfortunately for George in an area where many affluent and influential whites had built their mansions. Including one of George’s personal financiers. So he lost the backing of much of his black support.

Perhaps his major ambition was however to complete his, ‘History of Negro Troops’ and still with influence in politics, he saw the need for a monument for black troops killed while fighting for America. This proposal for a fitting monument he had hoped to coincide with the publication of his book in 1881. The proposed inscription, ‘A GRATEFUL NATION CONSECRATES THIS MONUMENT TO THE 32,847 NEGRO SOLDIERS WHO DIED IN THE SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY. THE COLORED TROOPS FOUGHT NOBLY.’ This was to be placed in front of Howard University, Washington. Despite being passed to send to the House of Representatives, it never got a hearing in there and the proposal failed at that point, whether on principle, apathy, objection or cost it is not certain. A problem was that when the Negro troops were allowed to flock to the Union colours, they discarded their plantation names and assumed the first name that came into their heads. These Negro troops were hooted and hissed at as they marched in column towards the battlefields to fight for the North and the American Constitution (as written in his History published in 1882). In this case, for those killed or wounded, their identity could not be easily determined, and the bounty put aside for veterans was thus denied them or their relatives. The influential, colored newspaper, the Cleveland Gazette suggested that, ‘What’s the matter with the proposition to have a portion of this fund set aside for a school of technology or a national school, business and the mechanical arts where our boys would not be shut out on account of their color? If none of these then something to advance these whom the dead died for?’ There was indeed a fund for veterans in the Treasury if, perhaps there was not the political will, or anyone to influence the political will, to prise the money out of the bounty fund and distribute it where it could be legitimately placed.

He hadn’t sought a second term in the Ohio legislature but had opted to concentrate on his ‘History of the Negro Race’. He left Cincinnati and moved to Columbus. Here, in proceeding to lecture, he was eventually elected to the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans’ league which continued to press for better compensation for injured soldiers and their deprived families. In a meeting in Columbus Ohio he was appointed Colonel of the GAR and where he speaks of the ‘gratitude due the soldiers and their families’.

In the boundless energies he expended in serious and demanding research for his books, he borrowed books from the public libraries of several cities and also private libraries. Though liable to a payment of fees, it seems he was able to smooth talk his way into borrowing, which was an evident skill of his and it was not only women who could fall for this smooth talk but also librarians or influential financial backers and statesman and, consequently, some fees were left unpaid. In his lecture tours for which he was paid, he was advertised and considered as ‘Colonel The HONORABLE GEORGE W WILLIAMS LLB.’ (He had been appointed to Judge Advocate for 1880-81and was the first ‘Negro American’ to be so.) He used James B Pond as a lecture manager to arrange his lecture tours, the same man who had managed tours for the likes of Mark Twain and Conan Doyle. George also wrote fiction and drama, finding time to do so in between writing his histories. His play, ‘Panda’ does not seem to have survived. His novel, ‘The Autocracy of Love’ about inter-racial relationships was turned down by publishers. He refused to change the content when asked, but it was eventually part published in the ‘World’, a Negro paper of lesser standing. This paper serialised eight chapters before inexplicably stopping the series.

He had left his home, where he had settled in Columbus, as he travelled widely and now he was away from home and by 1880, his critics could accuse him of neglecting his family. His first book was published in 1881 and he hoped he could make a living in publication. He was 33 years old and had written the book without any professional training. His books got cautiously good reviews and some naturally critical ones claiming he had presented nothing new. By 1883 having published his second book, he had decided to leave Ohio entirely as he had become fed up with the Republicans in the State and moved to Massachusetts. Feeling very let down by the Republicans in Ohio, he had claimed, ‘I shall not make sacrifices for anyone other than myself or my family – for Race of for Politics’ and it is evident that he moved with his family at this time. He felt that he could earn an income from writing, looking after ‘No 1’, and he continued to enjoy popularity as a public speaker after leaving Ohio and commuting between Boston and New York claiming to have a contract of $150 ($4,516.74; 2023) a month for writing. In public speaking he spoke up for the Negro who some whites thought hadn’t the capability to be educated and the sooner they could be sent back, using ‘repatriation’ as a euphemism, to Africa, the better.

In 1884 he was elected as captain of the Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. He was also involved in the Cape Cod Canal Company and a trip to Europe this year may have been connected to that in viewing the Suez Canal. He was unsettled and his wanderlust gripped him again and he was perhaps frustrated at not achieving the results that his ambitions demanded of him. Sometime in this year for his wedding anniversary, and probably before he left for Europe, he gave a large reception at his home, always wanting to give the impression of being as equal in intellect, social position and material possession as anyone else. While in Europe he made a point of visiting the grave of Toussaint L’Ouverture in Paris, a man to whom George would have felt very close in spirit and who was a freedom fighter who had nevertheless had to compromise in order to achieve the success of high ideals in the cause of the freedom and equality of the human individual. George visited several European cities but eventually, short of money and having borrowed money he couldn’t pay back, he had to return home.

In 1885 he settled in Washington, writing and lecturing and on March 2nd of this year, he was nominated for Minister Resident Consul General of the United States to Haiti (written Hayti). This caused a great fuss and there were many objections, both prejudicial and practical, which included debts incurred while in Europe. He borrowed money all the time on both sides of the Atlantic and had excuses for not paying it back. His debts thus worked against him over the appointment to Haiti. He had been awarded the post but after a change of Presidential administration this was denied him by the new administration. The newspapers took up the story. He had been awarded the post in Hayti and could have taken up the post, but the Savannah Morning News states that he would not file his bond which he is required to do by law. The Saint Paul Globe reports that he would not be able to take up the post since he had borrowed and not paid back the $10 ($313.5; 2023) from abroad. George claimed that it was such a small amount that it did not matter. However he attacked new Secretary Bayard for objecting to his posting, and the fact that he would not now be able to secure bondsmen for the post, disqualified him in the end. He subsequently brought a suit in the Court of Claims for the payment of the $7,000 ($219,473.09; 2023) as salary due as he claimed he had been officially appointed. The Middletown Argus argues that the ‘dusky humbug’ who was in the town with his ‘brilliant and boastful ways’ was not likely to get the compensation but needed the money because he was known to borrow and spend.

After the Haiti debacle his wife Sarah went to Louisville to stay, taking their son with her, and George and Sarah did not live together again. She used to travel with him when he moved temporarily from place to place but they had spent the longer periods apart. He sued for divorce in 1886 but could not prove desertion by his wife. It was claimed she was living with another man but she counter claimed that she had received no support from him since he had left for Europe in 1884.

In his longstanding interest in the indigenous African on the African continent, and after the publication of his books on the African element in North America, he went to Europe once more to research. In 1888, and now that the monument memorial question was finally defunct, he was in London to attend the Centenary Conference of Protestant Missions, where he had been appointed by the New York Committee of the Conference as the prominent black American. Here at the Conference there was mere resignation that the opium traffic from China and the liquor traffic from the Congo could not be prevented and thus evident that there was neither the will nor the means to change things. George argued that the same excuses were given for slavery in the USA – it had taken 80 years and a bloody Civil War to resolve the issue. To change things it was matter of good statesmanship and principle. That was the answer. George could always see the simple first and foremost but to break the resilient traditions to reach into that simplicity was not easy.

But he also used his time in Europe to research a biography of Toussaint L’Ouverture. He visited libraries in England, France and Spain and returned to the US with a mass of material for his book, though it turns out later that he left library fees unpaid. The Cleveland Gazette, a ‘colored paper’, ‘one of the best journals of the race’ in its 6th year which reports favourably on colored people, also reports that Col G W Williams’ has just returned from Europe and has with him ‘ten large royal octavo folio volumes of manuscript data’ which had been obtained from the libraries of Europe and he was at present writing the history of Toussaint L’Ouverture, once voted the most prominent Negro in American History. He was a hero of George’s who exercised, by necessity, the same necessary and uncomfortable compromises that George himself found he had to.

By 1889 the Haiti appointment had been the last chance to secure a foreign post and there was no other Government post open to him. At the time, anti-slavery leaders worldwide were calling for a conference to be held in Brussels and this took George’s focus. In July 1889 he published an article calling for the people of the United States to condemn the ‘gigantic evil’ of worldwide slavery, and called for an economic boycott of all countries engaged in the slave trade. So he sailed for Europe once more and on his way there, the reports were more concerned that he had fallen in love with an English girl whom he had met on the boat. She had been travelling with her brother and sister and though she might have been a constant companion and both would have no doubt enjoyed each other’s company, there was no indication of an intimate romance. There was also, regarding this claim, that a woman had even contacted the US consul in Liverpool, to enquire about inter-racial marriage in the US and the unfavourable advice persuaded her to decide against it. This was probably referring to this occasion as the regular transatlantic packet crossing from Boston was to Liverpool. It was also claimed that he had passed himself off as a bachelor when he was in Worcester (USA) and had left without paying his hotel bill, getting a friend to go along and collect his effects. But the same paper (Worcester news) claimed that he was the richest Negro in the United States and that he had affluent parents living in Europe, so the paper’s claims can be treated with scepticism. The Middletown Daily Argus, always keen to put George down, somewhat sarcastically reports that George is to marry an English girl he met on the boat over to Europe en route to Belgium. It gleefully claims that George was a lady’s man and would chat up any girl in any town at will. It made no mention of his current marriage. The paragraph was sub-headed, ‘Latest success in love-making.’ George replied to the accusations in no uncertain terms from Brussels.

Having failed to be appointed as delegate to the Conference, he had nevertheless obtained a writing commission to go as a journalist and reporter. His first commission was to interview Leopold, the King of Belgium, who had subsequently impressed him and he wrote in praise of him, as the King had assured him of his commitment to Christianity and humanity in the Congo and ‘Williams’’ obvious presence in Brussels at the time increased the focus on the anti-slavery Conference. He had formed a plan by then to visit the Congo for himself – this was when some influential white men wanted to transport back the American Negro to Africa. In this respect it was a land which could offer a great opportunity for them and this plan to visit the Congo was perhaps connected to this, reflecting the New Mexico episode previously, and George would have to see things for himself first of all. The Conference would also have on its agenda to address domestic slavery.

It was considered that, when George would visit the Congo, he could address the tradition of slavery with the Arabs, an established and significant human group, possessing a spiritual world outside Christianity. When he did eventually reach the East of Africa he would consider that, since General Gordon’s death, the slave trade in the area had increased and it was the hope of the Christian element of the West that he could influence the local rulers against a tradition of slavery, and to some extent he did find unprompted, favourable evidence.

The Conference of 19 nations opened on Nov 18th 1889 and George hoped to recruit black Americans to work in the Congo for which Belgian companies had agreed to pay him $150 ($4,958.59; 2023) for 40 American Negros. He left briefly for America again for just this purpose and arrived there on Dec 19th. George was only three weeks in the USA when he returned to Europe having failed to recruit the required black workforce of 40 men and, because his recruitment had failed, as he had told these companies on his return that it couldn’t be done, he was regarded with suspicion assuming that he might be undermining their commercial ambitions in the favour of others. There was also suspicion courting a possible conflict between both European and American ambitions in Africa as US President Harrison was reluctant to ratify the Berlin Conference in which King Leopold appeared to want to acquire the Congo Free State as the sole property of Belgium. George’s simplistic focus had to manoeuvre through the stark reality of the complex game of political chess, commercial interests and national rivalries.

Undeterred however, since he could see no end but that of his own, ultimate goals, George acquired sufficient assignments to finance his trip to the Congo and give President Harrison, whom he had met with and discussed in the White House earlier, the information required on the state of things in the country. While he was commissioned to write letters and reports to various newspapers and publications, his main benefactor and source of income was railway magnate Collis Huntington who was interested in constructing a railroad through the Congo and in which project, once more, young black Americans could go there to work to improve the country. Collis Huntington sent £100 (£10,574.23; 2023) to a London bank for George to draw on in order make the trip for information on the proposed railway route. With this money he purchased equipment and supplies for the trip. This increased the suspicions and antagonisms of his enemies, the Belgians, who warned of his ulterior motives in seeking the self-interest of his financial backers against their own interests. He even thought that his enemies, referring to the Belgians, might want to assassinate him and warned the US President that he would hold him to account if anything happened to him. Indeed he requested the protection of an American gunboat as a show of force on his behalf. All the time he was in Africa, he depended upon the Dutch mail for his correspondence as he didn’t trust the Belgians.

The journey to the Congo took 53 days, and at each stop-off point he engaged with the locals and enquired of their relationship with the Europeans. He found the living conditions and the lack of justice within the penal system deplorable. Africa was a cash cow for both European and US commercial ambitions, while living conditions for the indigenous people were appalling – the penal system was savage and even the dead, in a state of reduced usefulness to the living, were left out to rot and to be eaten by wild animals.

His remit in the Congo was to survey the route for the proposed railway as an observer rather than an in an official capacity, and in the end he considered it would cost twice the $10m dollars it had been estimated previously by the more famous Henry Stanley. He found that the terrain was more difficult than had been made out and the number of bridges needed would have to be more than doubled and the time taken increased to four years rather than the proposed two. He had set out with a caravan of 80 men on May 5th 1890 and while his own journey was romanticised in reference in film in years to come, Joseph Conrad, his contemporary in the Congo, based his ‘Heart of Darkness’ around his experiences in the Congo at this time while he was travelling up the river as captain of a river vessel. This novel would be translated into film as the Deer Hunter with its autocracy of madness played out with the backdrop of the savagery of the Vietnam War. The British diplomat Roger Casement, concurring with George, would also make a sympathetic report a decade later on the living conditions of the locals, and the two had met there at one time. Roger Casement, at one time working for Henry Stanley, would suffer execution for his controversial support as an Irishman to his homeland, in the highly sensitive and destructive conflicts of national identities of WW1. George would suffer illness and death at a young age, while Henry Stanley would receive honours and Joseph Conrad renown as an author. Each with a very different outcome to their lives, leaving their own sticky note to popular History, one achieving notoriety, one celebrity, one literary acclaim and, for George, obscurity. He would die quite soon, his destiny somewhat of his own making, at a place far from home, if he had anywhere to call a home, among people who didn’t know him and when even his fiancée didn’t know who he was. But he wasn’t friendless nor destitute for those who want to feel too sorry for him in misplaced, somewhat patronising sympathy, or for those who were glad to learn of the demise of a man who made a nuisance of himself by serenading their ears with a tune they couldn’t like. He was nevertheless able to survive by his wits and without any privileges as a birth right, and was able to successfully taunt out firm prejudices from the comforts of the established order.

During the exploratory journey to his destination at Stanley Falls, a journey which took him two months, he came across both friendly and unfriendly human groups, those unfriendly ones who didn’t want the heritage of their land usurped by foreign incomers with a different culture to them. They just wanted the caravan of foreigners to move on out of the way and so for George and his team on these occasions, there could be no bartering of blankets or goods for food but, on his return, he could proudly claim that not one man was lost on the journey there and back. He visited the Missions regularly on route and the missions could report back to headquarters in London with news of the man. Slavery was still practised in the country, something which both George and later Roger Casement would write about and condemn. Though some human groups he found to be quite prosperous others were on the breadline at the limits of poverty and conditions were generally appalling. A few observers might have been able to see this but there was no political will to change things. Roger Casement was there as a British diplomat and had witnessed a slave catching raid to collect porters. He would write in similar terms as George about unfairness and that a Congolese was merely a possession of the State and had no rights. Though some improvements had been made, torture and severe mistreatments still persisted in the penal system. Joseph Conrad didn’t meet George Williams but he had met Roger Casement and subsequently wrote to him surprised that, though slavery had been abolished, it still survived in the Congo. While George did not come across Henry Stanley on his travels, the two had met in New York though there is no report of the relationship between the two there. They might have been friends then but, if so, then observations in the Congo would change that for both of them.

By Stanley Falls, having seen enough, and perhaps more than he might have wanted to see, he wrote his famed and highly critical Open Letter to King Leopold of Belgium. He was especially suspicious of the Belgians who he had severely censured for their treatment of workers on the railroads. Though these workers had no chains about their necks they were treated like slaves by the Europeans and he complained that King Leopold was not that concerned about human beings when the advantages of profitable and successful commerce were available. His journey through the Congo convinced him of this as he saw the inhumanity exercised by the king as figurehead, and that the king had sold his vested interest to commercial companies and thus had no control over the land. It was this that inspired him to write his Open Letter. Stanley he claimed had bribed the chiefs of the local tribes into giving up their land to the white man in the name of King Leopold. Annexing land was just a rip-off and no concern for the inhabitants given. His findings make grim reading. Villages were raided and men taken for the workforce and the women who had no rights at all and could be bought and sold at will to the highest bidder. In effect the Government in the Congo was involved in the slave trade by its lack of action. Previously, perhaps, this had been the privilege of the indigenous African nations, with the differing identities and languages, in their expanding migrations and equal self assertions of culture at the expense of the conquered.

It appeared to George that Henry Stanley was a bad man and allegedly had a temper and would beat the natives if he felt justified. He had claimed that the land was fertile when it wasn’t for most part, and he was guilty of many a broken promise. He refuted Stanley’s claim of the railway cost and that he had grossly underestimated that cost and the time needed for completion. There was enormous wealth in the Congo and the industrialists with interests in the land turned a blind eye to the harsh conditions of the workers – they preferred to believe the king, Leopold, than George Williams. The Open Letter caused quite some concern and George was accused of blackmailing King Leopold. ‘Williams’ was vilified as much as his detractors, who had self-interests in the Congo, could do so and the press had a field day for his audacity to impugn the King of Belgium where he claimed that the Government was involved in the slave trade and the fact that the Arabs, with a tradition of slavery, were also not kept in check or questioned. On the return trip to the coast, George was treated as a celebrity by the people and he then travelled in Africa to various places meeting Zulu and Kaffir, all the while investigating possibilities of Huntington investment which was financing his journey. He had all the statistics and would present them to the European authorities of the particular colonies he had travelled through on their behalf.

At the end of his journey, he came back through Aden and then, on arriving in Cairo on Jan 21st 1891 in failing health, he became hospitalised. Close to death he had with him three written reports on the Congo and six journals of valuable information. George had alienated friends who had interests in Africa by speaking out, and now he needed friends as he lay ill in Cairo. His attack on Stanley hadn’t gone down well. Huntington, his primary benefactor, was especially not pleased and relations cooled between them. Stanley considered Williams actions were an attempt by blackmail to get the King to concede the commercial advantage to Huntington the financier who would then get his own way regarding the railway construction. George in reply had written that he would bring action against Stanley for slander.

However, he recovered sufficiently from his illness, and he was given a free passage to London by Collis Huntington and his hospital bill was paid up and he was given some money by those who were normally critics of his but for some reason had changed their minds, each no doubt wanting the full reports for which their money had supported.

England and Blackpool

He left Cairo after a sufficient recovery and boarded the SS Golconda at Ismailia to take the passage to London. On the journey he had met up with Alice Fryer, a young woman from Southsea in England, who was governess to a British family in India and was returning home with her mother. George and Alice developed a strong and close relationship and by the time they had reached London, they had become engaged. Though it seems that he was always comfortable in female company, and she could have easily fallen for him anyway, the stories of his travels must have fascinated her further than this affable male personality who could show a keen and respectable interest in her and could attach a natural feeling of importance to the sensitivity of her own femininity. In George, however, there was a certain amount of honesty lacking in his need to be the ordinary person he could never be, and Alice was not aware of that. In London the three of them stayed at the Morley Hotel in Trafalgar Square where he left much of his baggage including his large collection of African curios.

He was now suffering, as diagnosed, from congestion of the lungs, a feature of his continuing ill health. Even in 1886 while he is arranging for the publication of the ‘Military History of Negro Troops in the War of Rebellion’, the Middletown Daily Argus of September of that year states that ‘Williams is still in precarious health’. The year from 1888 to 1889 had been a year of illness for George and he was unable to write at all during much of this period. Now in London his life expectancy was judged to be only two months, with that diagnosis, exacerbated by his quite demanding sojourn in Africa. Alice was much more hopeful, or wishful perhaps, of a recovery. George, feeling lucky to still be alive and wanting to live long enough to complete his work on Africa no doubt capitulated to the need for her female company to brighten his spirit and assist his recovery, in which case he perhaps felt that the truth of him being a married man didn’t need to be mentioned.

Perhaps also unknown to Alice, George Williams hadn’t paid the search fees in the London library when he was there in 1888 – more kindle to the fire of those who wanted to criticise him but, no doubt, he might have been able to convince Alice that there was a good enough and legitimate reason for that. Alice was naturally very concerned about his health so, with her mother, they took him up to Blackpool, encouraged by the renown of the health giving properties of its seaside airs, arriving there on July 7th 1891. Here the party took three rooms at the Palatine Hotel in the resort, George no doubt continuing his claim of wealth and putting the bill in his name. They took regular walks along the sea front, sometimes together, occasionally all together no doubt, and George occasionally on his own. George was nothing if he wasn’t sociable and in that time was able to make good friends with James Howarth described as a real estate agent and, most probably the JP, chairman of the Blackpool Aquarium and the future mayor of Blackpool by 1901. No doubt George had made enquiries about the whereabouts of a Baptist Church in the town and so became acquainted with the Rev Samuel Pilling (written occasionally as Pelling) pastor of the only Baptist Church in Blackpool situated on Abingdon Street. George’s health appeared to improve a little bit but, on July 31st, he caught quite a severe chill and became very ill. The next day Alice and her mother called the doctor who at the time was Dr George C Kingsbury another future mayor of the town from 1899-1900, and a local councillor at the time and, as a doctor, a man also of controversy, who diagnosed his lungs ‘were all but done’. George died at 4.45am August 2nd 1891 in the presence of Alice, her mother, Rev Pilling and Dr Kingsbury. The official cause of death would be determined later as ‘phthsis 1 year; and pleurisy 4 days.’ That is to say, perhaps in modern terms, TB with complication, Iguess.

James Howarth insisted that George’s body should lie in state at his home which would be Percy Villa, 20 Dean Street, South Shore and Rev Pilling conducted the brief funeral service at the Baptist church on Abingdon Street in the town from where his body was taken for burial at Layton cemetery. James Howarth also paid all the burial expenses.

Alice was distraught, though she didn’t know that George was already married until after his death and his affairs were being sorted out. She eventually returned to Southsea with her mother, but she was in constant contact with the US officials. She especially wanted the return of about 24 photographs of herself and George in London (though it seems that the London photographer hadn’t been paid for these photographs). She also wanted returned all the letters between them from his effects, but the authorities were unable to do this until all the legal requirements had been satisfied and the next of kin had been informed. It does appear that she had the photographs returned to her and it can be well imagined that she would have burnt them. Good for her perhaps but a pity for history. A Thomas Crawford, whoever he was and who was from Belfast comes into the story in an apparent official capacity, sanctioned it might seem, by the US consul in Liverpool. It was this Thomas Crawford who paid the hotel bill at the Palatine Hotel and leapt to Alice’s defence of any wrongdoing in her relationship with George, and further claimed it was a good job the relationship had ended for her before it was learnt that he was already married, his sympathies being directed to Alice.

On George’s death the US officials had been immediately contacted in London and instructions were sent to Thomas Sherman the American Consul in Liverpool to take the appropriate consular action. The manager of the Palatine Hotel had already telegrammed the Consul in Liverpool asking if he knew anything about the American who had died in his hotel. All he knew of him was that he was an American, and that he had travelled in Africa recently and George’s travelling companions would not have been able to tell him much. The Consul in Liverpool sent a clerk to see to the funeral arrangements and to look after the effects of the deceased which he did with diligence, it seems apparent. An advert in the London Times inserted by the Consulate there asked for information on George and his friends and family, since there was little known about the man and the relevant people needed to be contacted before his effects could be released.

Alice, even though close to him, knew little about him too, but she did know he had told her of an aunt who lived in Worcester Massachusetts, and who was later revealed as Lois Staples but, when this claimed aunt was contacted, she was at pains to distance herself from George and wanted all letters between the two returned to her. This legally couldn’t be done because it was a part of the deceased’s estate, and she turned out not to be an aunt at all but the woman at the address he was staying at while in Worcester. As just a passing acquaintance, her reluctance to speak, and that she wanted the letters returned, might mean that there had been a romantic attachment. There was a brother, Harry, 11 years his junior revealed as living in Dunsmour California, and an even younger sister, Lola in Sacramento in the same State. Both made enquiries to the Consul. So no-one who had met George had known him for a very long time and hadn’t got to know him well, or at all, and knew little about him. In himself his circumstances were insignificant to his own drive for truth to iron out the confusion of human relationships. If he had wanted to be an ordinary man, he was never destined to be just that. His siblings (he had two other brothers but these do not appear to have contacted the Consulate at this time and nothing is known about them) would have had little knowledge of him as he had been away from home at an early age and he would have been quite remote to them too, it can be understood.

His wife Sarah was still alive and living on 15th Street NW Washington DC. She eventually heard of his death and enquired of the Consul about her husband’s personal effects which were described as clothes, plenty of African curios (described in detail in his biography by John Hope Franklin), and there were the 24 photos of ‘Williams and Fryer’. His creditors became excited when the African curios were put up for auction as they expected to get their money back in full but were disappointed when there was not enough after the auction realised only $248.95, ($8,321.72; 2023). In consequence, the agreement to the creditors was to pay off a portion of the debt, about 50%, with the proceeds, but the Palatine Hotel manager was the only one to refuse, wanting his full share and kept hold of those effects of George which remained at the hotel. As a creditor, and realising there was not enough to reimburse him he had claimed for the total hotel bill as well as extras like the wine bill for the company of three. Here at the hotel, there were some manuscripts and a watch and chain which the Consul intended to send to Sarah for her son. Thomas Crawford had paid for the hotel bill and James Howarth the funeral expenses and that just left the wine bill as unpaid. It is probable that the unfinished manuscripts were returned, but it is uncertain whether George’s son received the watch and chain. George’s wife Sarah did in fact receive as much as Sherman, the American Consul in Liverpool was able to provide and these might have included these manuscripts which would not have been much use to a hotel manager. Alice Fryer, who must have been quite devastated at George’s death, as well as further distraught about his deceit, received as much as what was relevant to her as the consul could equally provide.

The Blackpool Gazette and Herald included this small paragraph in its Friday August 7th edition: – ‘Colonel George Washington Williams, an African explorer and traveller of some repute, who had been staying at the Palatine Hotel for the benefit of his health, died suddenly on Tuesday morning, as the result of a chill. The body was afterwards removed to the residence of Mr Howarth, of Dean-street South Shore, a great friend of deceased’s. Colonel Williams was, I understand, preparing a book on his voyages. A sad feature in connection with his demise is the fact that he was about to be married, his affianced wife and her mother being in Blackpool at the present time.’ The same story appeared in the Fleetwood Chronicle. Quite coincidentally on the same page as the notification of George’s death there is an insertion in the Blackpool paper from a correspondent of the Tatler whose mind was changed about Thomas Gray’s elegy in a country churchyard as he strolled through Layton cemetery. Here he found the Blackpool cemetery changed his views on the uninspiring and morbid nature of the graveyard of a country church and instead it was evident to him as, ‘a paradise of roses which smiled at you from all conceivable corners as though determined that dull care and melancholy should not have a chance.’ These roses ‘shed abroad a fragrance which was unspeakably refreshing. It was a beautiful scene – indeed, I should say it constituted one of the most magnificent collections of roses in England.’ Perhaps those who would want to share a positive view of George Washington Williams might want to claim that he was the first American rose to arrive in the cemetery even with perhaps a couple of faded, outer petals but, with a scent equal to any in the graveyard, one which might overcome, in its honest expansion of fragrance, the stench of holocaust which is the continuing selfish and aggressive nature of humanity.

In a misunderstanding of George Williams, comments in the US were usually unkind, though his brilliance of mind and speech had always to be accepted. The Middletown Argus reports that George, a Boston lawyer, died alone and friendless in Blackpool, a town in Lancashire, England. He had arrived some years earlier in Middletown, Ohio, to write his History of the Colored people of America, evidently flamboyant and spoke of his wealth, and the citizens remember him ‘clad in purple and fine linen and was bedecked and bedizened with jewellery’ and, according to his own story, was literally ‘rolling in wealth.’ He had promised to pay off the debt of the Baptist Church there and established himself in a fine house with a secretary to assist in the writing of the ‘History’. From the image of a wealthy man he was able to borrow, it seems, quite considerable amounts from tradesman etcetera, but eventually it became evident, after he had left town, that he was not able to pay off these debts, and the citizens quickly lost faith in him. His expected remittances from his publishers were not forthcoming to pay off his debts so he had left for New York to establish just why, he told them, and a lot of admirers saw him off at the train station unaware that he would not be coming back. In Middletown ‘He was a man of good education, was blessed with a good address and had a fine command of language and a most ingratiating manner.’ It appears evident that these were George’s lifelong stock in trade and assisted him in achieving great things without the back-up privilege of material wealth to do so.

In 1925 the American independent Negro paper The Northwestern Bulletin Appeal, as well as speaking out strongly for the ‘colored man’ has a brief biography of George Washington Williams which concludes, ‘Mr Williams was an able lawyer, a forceful writer and an eloquent orator. The race should commemorate the memory of George Washington Williams. He wrought well in his day to pave the way for the recognition of the educated Negro and to uplift the entire race.’

Since then he has been largely ignored – most black historians were – blacks were not seen as important. There had been black historians before as far back as the 1830’s but these had not been very good according to George’s biographer. It took the dogged determination of his biographer, John Hope Franklin to track down his story in those parts of the world that George had trodden. He met up with George’s wife who in good old age still had some of George’s writings and effects which proved useful in constructing the biography and in doing so, reconstructing the man himself. In re-treading the footsteps of his subject, it was an integral part of his work to come to Blackpool to make enquiries and to make that pilgrimage to George’s grave site to lay a wreath. From the unmarked grave on that day in 1975 there was soon the shiny black granite monument with its identifying inscription, which marks the site today.

Sources, Acknowledgements and further Reading.

Thanks to Denys Barber and the Friends of Layton Cemetery for the original information and grave memorial pictures and to Robert Leach for generously supplying images from his collection.

George Washington Williams A Biography. John Hope Franklin. Available in hard copy, a part read in Google books or a free read at https://archive.org/ though a small donation is always appreciated here. Without this biography and the extensive and persistent research of his biographer, little would be known of George.

John Hope Franklin

https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Washington-Williams

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hope_Franklin

The Civil War;-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Petersburg

The Mexican War;-

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maximilian-archduke-of-Austria-and-emperor-of-Mexico

British Library Newspapers accessed via findmypast;-

https://www.findmypast.co.uk/search-newspapers

American newspapers accessed at;

US Dollar inflation calculator;

https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1873?amount=100

Pond Stirling inflation rate;-

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

Blackpool archives;

https://www.showtownblackpool.co.uk/news/latest-news-on-showtowns-history-centre

Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language (physical copy) for the Presidency of William Taft.

Colin Reed July 2023