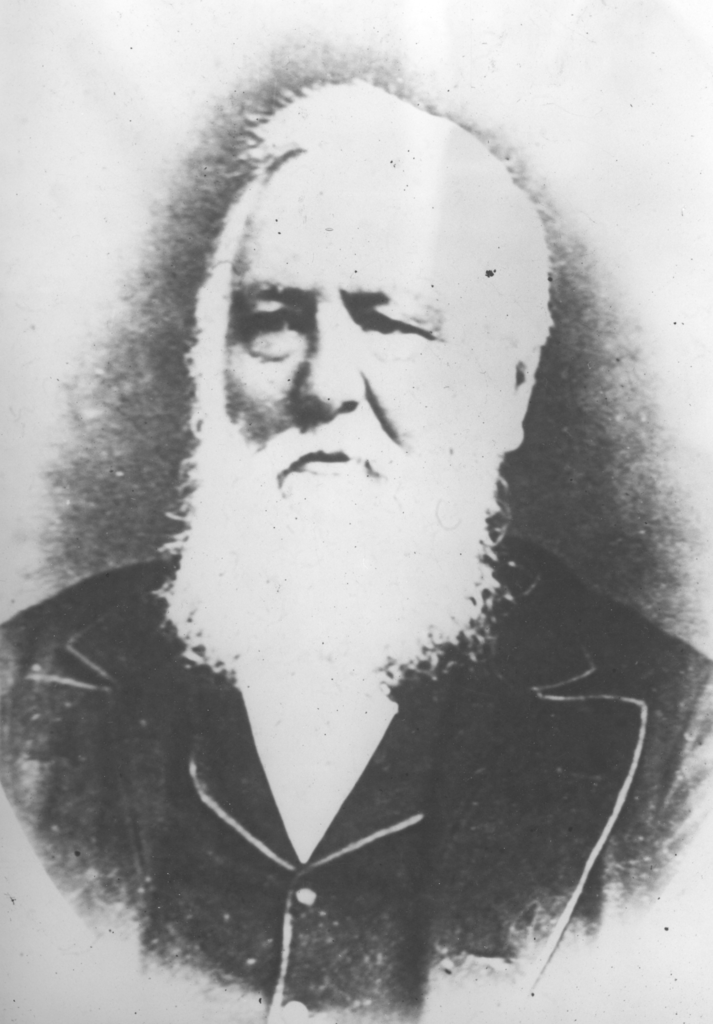

Dr Spencer Timothy Hall.

‘Possessing a nature of intense tenderness and a poetic sensibility peculiarly attractive, with a sympathy for suffering in every form, small wonder that Spencer Hall was admired and loved by all who came within the sphere of his influence.’

‘The ‘Sherwood Forester’ is one of those men who have risen to considerable literary distinction, and large moral influence by persevering labour and self-cultivation, animated by a poetical genius, and ennobled by high and pure religious aspirations.’

‘A tall, strong manly, simple hearted man was Spencer T Hall, one of those who win reputations, and are capable of vast labours, but who have no talent whatever for succeeding in the worldly sense of that term. He was one of the earliest and most enthusiastic exponents of what are still sometimes called ‘fads’ he took up with homeopathy, with mesmerism, with phrenology, and I know not what besides.’

A ‘jack of all trades’, a man who could, ‘plough and reap, stack and thresh and winnow, make a stocking and a shoe, write a book and print and bind it and cure all sorts of ills’.

These are just a few of the sentiments expressed by close friends and associates about the man known in literary circles as the Sherwood Forester and in medical circles as Dr Spencer Timothy Hall. He was also an early practitioner of the cutting edge fringes of medicine allied to the science of human behaviour which in the infancy of its understanding engendered much criticism.

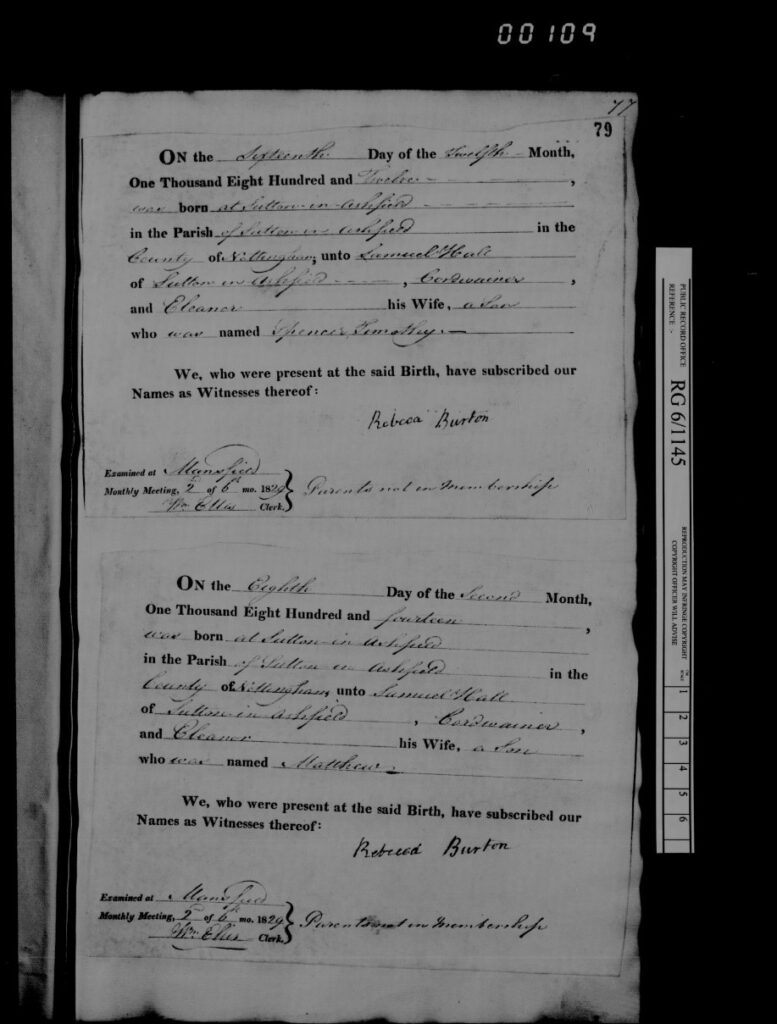

Spencer Timothy Hall was born on December 16th 1812 at Brookside Cottage a ‘low but pretty thatched cottage’ in Sutton in Ashfield, in the Mansfield district of Nottinghamshire. From humble origins, his stout frame, physical stamina, intellectual energies and perseverance through adversity took him all over the country in pursuit of the hidden truths of life, and where the discovery of each truth might assist in curing the physical and spiritual illnesses of humanity.

His father, Samuel was descended from a family of well to do tenant farmers and was a well-connected and respected man in the community, his own brother Timothy being a reasonably wealthy tenant farmer among them on the landed estate. The ‘pretty thatched cottage’ that he lived in was a row of cottages called Brookside and occupied by home workers with their looms involved in the local stocking making industry. So while the cottages might have been ‘pretty’ to an observer looking from the outside at a distance in time and space, they contained on the inside all the trials that a hard working and economically deprived group of human beings would experience in their lives. They were cotter tenants, those who own nothing but lived in a landlord’s cottage for expected services in return, a bit like a mediaeval serf at the bidding of the landowner. Samuel was a man of many talents and honest industry, and a head full of ideas stirred up with a bright intellect and inquisitive mind, and a highly useful tenant well worth a free cottage, no doubt.

Long before the birth of Spencer, Samuel had fallen on hard times, losing most of his material wealth in the process. His material demise and misfortune occurred when he took up business with an unidentified, distant relative, but this distant relative being a dishonest man and Samuel in his honesty, though a man of many talents, was not cut out for the job in hand and lost all his investment. He then had recourse to working on the land of his landlord in a tied cottage as a cotter-tenant. There is a clue to his demise in the record as in 1799 he had invented a machine for cultivating turnips, but it seems that without a patent on the machine, he lost out to competition which took over his idea and the ‘dishonest relative’ might have been this culprit.

Samuel was originally, as a Quaker, a member of the Society of Friends. He had however been excluded from this Society ‘due to his marriage’ He was nevertheless buried in the Quaker burial ground at Mansfield, on his death in 1852 at 84 years of age as was his wife Eleanor on her death in 1830 at 56 year’s old. Eleanor, whose birth surname was Spencer carried on the tradition of the mother’s name being included in the name of one of the children and this was maintained with Spencer Timothy, her first child with Samuel. Her first husband James Bacon ha died in 1805 after they had had two children together, Hannah and James, having been married in 1801. It is perhaps only possible to determine the exclusion as having an association out of wedlock. While Samuel was a man of principle, his natural instincts were pure and gentle and indeed fulfilled and for the couple, a physical association, which would, it could be expected, have contained a love and respect for each other, might not have appeared out of place within the tenets of their religion. The records show that the marriage between Samuel Hall and Eleanor Bacon (Elinor or Ellen as variously spelt) took place in June and the birth of their son took place in December of the same year of 1812.

Spencer was taught weaving and stocking making and became quite multi-talented. His father as a man of some literary interests and achievements had written at least two books, ‘Samuel Hall’s Legacy to Professors and to the Profane’, and a ‘Culture of Turnips’, the one a treatise against swearing and the other with an evident horticultural content, two subjects which in their stark contrast and the width of their spectrum of interest might have influenced the mindset of Spencer as he searched for those satisfactory intellectual truths in life, in places that would eventually seem unlikely to those of his generation.

His mother, Eleanor, was a ‘warm, bright, stout, active little woman’, stout in morality certainly but whether stout in physique is not made clear. She is described as a milkmaid and a shepherdess so must have possessed some stamina without the additional, natural burden of childbirth. Spencer’s early education at school was probably at a Quaker school and at home is attributed to a ‘generous step sister,’ which would be Hannah, who encouraged him to read and get enthusiastic about intellectual pursuits. Ultimately he preferred to follow the paths of his cerebral inquiries rather than settle for agriculture and the menial tasks of the land or the stocking maker or the cordwainer within the walls of his home. His other siblings with his parents, were brothers Clipstone, Matthew and Daniel and a sister, Sarah. Spencer was the eldest of the five children, who were all born between 1812 and 1819 and each are described as cordwainers on the register of the Society of Friends for the Mansfield district. So it was all hands to the pumps in the Hall household regarding the shoemaking business. Clipstone ended up in the workhouse at a later date by 1881, where there is also an Alfred Hall. Alfred, is described as a stocking knitter, and is not identified as a sibling. Clipstone here is described as an ‘idiot’ and on the 1851 census with only he and his father at home he is also described as an ‘idiot without speech’ and annotated on the form as ‘dumb’. It would be interesting to learn that the term on the census return form was used because there was not another word in the vocabulary at the time for Clipstone’s seeming idiocy through his lack of ability to speak, and whether Samuel was aware or complicit that his son was being described as such on the form. For eight years after his brother’s birth, Spencer Timothy, would have been at home with him, becoming competent at the designated family occupation. Perhaps in his intellectual restlessness, his brother Clipstone’s condition fired a desire to explain the human condition and seek a cure which stayed with him till his dying day. Each day with his incapacitated brother would not, it could be expected, be one of dismissal and contempt but there would be those lasting moments of connection, and care, appreciation and love within the family.

Spencer was a studious pupil and was a keen reader and when he read the life and works of Benjamin Franklin it had a great influence upon him. It was a kind of epiphany, opening up the future for him and it made him restless for its exploration. But he always maintained a strong moral theme in his life edified perhaps by those family ties bonded by a mutual consideration and protection of a less favoured sibling, supported byhis Quaker upbringing. He would query many things but stalled at a query of a Christian God.

While at home, up to about his sixteenth year, if his head wasn’t in a book it was in the natural world of the forest and fields all around him, or by, the ‘brook’ which gave its name to the Brookside cottages, a tributary of the river Mann that ran by the foot of the garden. But Spencer’s intellect was restless and reached beyond what was evident to the eyes and he is recorded as having run away from home several times. On one occasion his father who was an accomplished pedestrian, walked the sixty miles to grab him by the collar, as it were, to bring him back. Pedestrianism, was one of those extreme Victorian sports, like swimming, ballooning, parachuting and diving, though for Samuel it was a natural ability not a challenge or a profession.In the September of 1852, long after Samuel had set off after his son, a chap called James Yates walked about three thousand times around the Number 3 public house in Blackpool and it took him just short of six weeks. It didn’t take Samuel six weeks to go the nearly sixty miles to get his son, though, at sixty years of age, he had set off at 3 o’clock in the morning and returned by 9 o’clock at night without undue physical detriment. But perhaps for James Yates, it was worth it for the £100 (£14,854.32, 2021)prize money. Samuel for his part, got his son back who was worth far more than a monetary reward to him. He had also walked seventeen miles on a hot summer’s day on another, undisclosed ‘errand of kindness’, so he was quite a physically fit man. Spencer had inherited his father’s robustness of frame and generosity of spirit, it seems, as well as his mental energies and it was a little, or a lot, of ‘like father, like son’ between them, (Samuel referred to Spencer as ‘a lad after his own heart’). Both had a commitment to religious principles, unqueried but occasionally perhaps compromised.

But one time Spencer left permanently to find his own way in life, and his father didn’t bring him back. By this time in 1829, he had reached sixteen years of age and, dressed unobtrusively as a country Quaker he set off with a couple of books and thirteen and a half pence (8p; £14.60) in his pocket and walked all the way to Nottingham through the winter snow of January, sleeping out in the open wherever he could find, at one time in a snowdrift where he got no sleep at all. But he was young and fit and healthy and he reached Nottingham and was successful in acquiring a job as an apprentice compositor at the Mercury News in the city and finding accommodation at the home of his master. Here, he immersed himself in books and self-education until, in about 1837, after a seven year apprenticeship of hard work and long hours where he extended the day further in his own reading of philosophy and poetry, he became editor of the Mercury for a short while, now contributing articles to several other newspapers and became associated with many writers and literary characters including being introduced to William Wordsworth. Thus he became a respected member of those literary circles. In 1840 he published his first book, ‘The Forester’s Offering’, a book of prose and poetry about the natural landscape of his boyhood, not only creating the manuscript but also composing the typescript. He had become known by the nickname ‘Spencity’ by now, though whether the accent on the ‘e’ or the ‘i’ is not known. It preceded the pen name of ’Sherwood Forester’ by which he was to become generally known.

In 1835 he had married Elisabeth Wells in Radford and at some time after leaving Nottingham he returned home to Sutton it is reported, to set up his own business though this is not corroborated in the records as seen. He did however, around this time, work at York and Sheffield on the local papers, being co-editor of the Sheffield Iris when at the same time his, ‘Rambles in the Country’ was a success and earned him the favourable reputation as a writer and he continued to keep the company of writers, poets and journalists of note. In 1841 he is in Sheffield as ‘writer for the press’ on the census of that date and his wife Elisabeth is with him. While in Sheffield he took the residency of the Hollis Hospital, a charitable institution where he was able to enthusiastically study both the physical and psychological aspects of the human being, effusing his natural compassion for his fellow creatures as well as exercising his curiosity. By the age of 29 he had become a Doctor of Medicine, a title received from the University of Lubingen in Germany. This seems to be an honorary title not one received as the result of the successful pass in examination, and it was a little before this time that he set off around the country on his lecture tours which were generously attended as ‘the crowds flocked’ to them, his fame reaching far and wide and institutions of note were keen to hear him speak and demonstrate. While his mother was dead by now, having been suddenly ‘seized with a fit of apoplexy’ and dying shortly afterwards, his father was able to attend one of his lectures, proudly sitting near his son on the platform. His poetry which he had continued to write was now added to by biographies of the noted people of his acquaintance in this, his golden era of fame and popularity, and his output of prose and poetry was at its height. At this time he was due to lecture at Windsor and to travel to Russia also but it is not sure if either of these took place as at the time he was struck down by an unidentified spinal complaint which kept him hors de combat for a while.

It had been in 1840 that Charles La Fontaine had come to England from his French homeland, one of the places on his itinerary being Nottingham and Spencer attended his meetings as a member of the press. La Fontaine’s demonstrations of animal magnetism captured the imagination of Spencer and presented an area of undiscovered intellectual countryside that appealed to his inquisitive mind and the search for truths whether relative or absolute in their clues, and could question the speciousness of what were deemed self-evident truths to those committed to the conventional. The idea of animal magnetism, or more popularly, mesmerism, appealed to him and he could see in its practice the potential cures of many human ills that were currently incurable. From being a student of the phenomenon, he became a practitioner himself and began lecturing in Derbyshire and then at Sheffield.

Mr Spencer Hall had always been a clear and convincing speaker and his ingenuousness won him the admiration of many including men of science as well as literature, and he had significant success in his cures, through the practice of mesmerism. A most notably patient was Harriet Martineau, writer and sociologist though she, and indeed Spencer, came under criticism by the hard line conventionalists, even though the cure had clearly worked. Harriet was not a woman to mess with and she defended Dr Spencer while holding her own against the critics. His practice in his lectures is similar to the faith healers who believe the hand of God is active in their explanations of the success of any result. To Spencer the explanation was hidden somewhere in the obscurity and the lack of a proper understanding of the science involved in the process. Thus when a woman who had not had the use of her arm for years, was cured by his hypnotic techniques, the explanation was not one of God but one of science, though God clearly existed for Spencer and he didn’t see the need to deny ‘his’ existence as God, and in argument, could be the creator of science, anyway.

Spencer would become used to controversy and what was evident to him was more than evident, and the evolution of medicine paused at convenient times and became complacent, not wanting change. So, as early as 1845 while immersed in the intellectual activity of his London days at the City of London Literary and Scientific Institution, drunk on the self-confidence of his beliefs on mesmerism, he challenged the whole of the medical profession to ‘come outside if you’re hard enough’ and I’ll take six of you on at a time as much as the false confidence of a drunkard might feel able to take on the whole of the world in physical combat when he(or she) had had more than one too many. But Spencer was eloquent in speech and persuasive in language, likeable in expression and genuine in sentiment though it is not known whether there was a confrontation – of the non-drunken kind – in a spot chosen by the doctors who had been challenged. Perhaps he was best left alone and they were safer in the confines of the non-controversy of their complacencies and well away from the consequent impugning of their reputations which might result in the reduction of their incomes.

Having married in 1835 in Radford to Elisabeth, they had lived together, or at least been associated as man and wife, in Nottingham and Sheffield and probably Sunderland, too for nearly fifteen years. Elisabeth isn’t with him in 1851and Spencer is living in Pinxton describing himself as a ‘poet and philosophical practitioner’ and staying at the house of a retired barrister alongside Joseph Briggs who is an agriculturalist and naturalist and a Mary Ann Davey who isn’t identified further, and complemented by a house full of servants. All three are visiting so it may have only been a brief time away from his wife. Elisabeth had had enough before 1859 when Spencer filed for divorce in on the grounds of the adultery Elisabeth. It is stated that Spencer returned to Sutton in 1836 and it is about the time that the marriage was in a settled state as he had set up in his own business in printing and selling books and Elisabeth was good shopkeeper. But he was not one to stay long in one place physically or mentally and especially after 1840 when he had been hooked on mesmerism and he was constantly touring the country, that the strain on the marriage became understandably too much for his wife. Elisabeth had at first, it seemed, travelled with her husband on his lecture tours but when he became enamoured with the intellectual life in London and remained there in Clapham, she was reluctant to join him. She did make the journey to visit him in his consulting rooms in Pall Mall but caused a nuisance of herself, as reported, as she seemed, understandably, to need a resolution to their relationship, and a separation was advised by friends and agreed between the two. When he had married Elisabeth he was plain Mr Hall but by now he was Dr Hall and she, as his wife, would naturally have valued intimate personal attention from Mr Hall more than intellectual discussions about arcane subjects as Dr Hall. The separation was arranged and Spencer agreed an allowance of 12s (60p) a week until he discovered that she was living in Sheffield with a Mr Hill and he then gave her 20s (£1) as a final amount if she were to keep away from him, that is, he, Spencer. Thus, no doubt in a natural way needing the attention of a male partner, she had had an affair with her widowed brother in law, who was the Mr Hill. This relationship came to an end when she began seeing a Mr Walker, inducing Mr Hill to leave for Australia. She then set up home and business in Sheffield with this Mr Walker living obstinately in the face of the world, as man and wife. The decree absolute between Elisabeth and Spencer was decided upon without question by the court but costs were not applied for. At this time Spencer must have had sufficient money to live on reasonably comfortably. It is true in reading the (limited) correspondence, that he enjoyed the sound of words and the complexity of language and sentiment which, when he evolved from a printer to a doctor, estranged himself from his wife who only wanted the simplistic language of love and the confidence that attention brings where the sweet nothings did not flow off his tongue in floods and into her need for attention. In those intimate moments it is reasonable to understand that a few words of love and attention would go further than a discussion on phreno-magnetism. Those discussions could be left to the lecture hall where in 1843 this magnetism was demonstrated in Nottingham in the New Hall in Wellington Street when a young man was magnetised, or hypnotised as it would be referred to eventually, and at the command of the magnetiser, and entirely successfully in front of an interested audience.

Thus, divorced in 1859 he re-married in the same year in Derby, to Sarah Blundstone, a marriage that didn’t last and there is a death for Sarah Hall in 1860 in Derby which might be the same Sarah as on the 1861 census for the town. Spencer is a widower with probably the longest description of any occupation that can be found on a census return. He was married again in 1861 to Mary Julia Grimley whose father was a ‘gentleman’ and possibly a man of some means and connections and for some reason they went all the way down to Brighton to get married, though Mary was from Donisthorpe, a little village in Leicestershire. Both marriages are in the records but there is no indication of why the first one failed possibly because of the demise of Sarah, through the dangers of childbirth perhaps, given the short duration of the marriage. There are no children found for his marriage to Elisabeth. It was Mary who lasted her days with Spencer sharing in, no doubt, long suffering, his poverty and his restlessness until his death in 1885. In the later marriage record, Spencer’s address is given as Derby and Well Field House, Matlock. Mary, much younger than her husband, outlived him and died in Manchester in 1916 when she is remembered only as the wife of Dr Spencer Timothy Hall.

But back to the 1840’s. By 1845 Dr Spencer had published his, ‘Mesmeric Experiments’ and soon moved to London and frequented the British and Foreign Institute where many men of letters and science and art gathered for regular soirees. Here he associated with the familiar names of the day, including Charles Dickens, Mary Mitford, Mrs Gaskell, Robert Owen and many other names less familiar today. And he didn’t entirely divorce himself from the family as his father came to watch him speak about mesmerism before an audience of 3,000 people. In 1848 he attended and spoke at an anti-capital punishment lecture in London, where it was maintained that the ‘punishment of death is opposed to the spirit of Christianity’ and that it ‘sometimes involves the destruction of the innocent’ by the judicial process. Spencer’s eagerness to probe the recondite and least understood aspects of the human mind didn’t call into question his own deeply rooted religious beliefs. He made a good impression at his lecture in Lincoln entitled, ‘The Human Temple and its Relation to the Soul’ which though very practical and insightful in its originality and its subject matter of conversation and diagram on human physiology did not break away from religious convention and a vote of thanks was enthusiastically seconded by the Reverend C Scott. Indeed in Ilkeston in 1857 he took to the pulpit at the Primitive Methodist Chapel which had just been refurbished and gave two lectures, one in the afternoon and the other in the evening. These went down very well and both were listened to with great interest, attentions held firmly by Spencer’s speaking style and ability. Though evidently belonging to no religious sect, his religious precepts were nevertheless Christian and he quoted the bible and referred the physical nature and attributes of the human body as being the design of the Christian God. So he was able to hold an audience’s attention in a spiritual area where an atheist would have found it impossible. The collections during the lectures for the cost of the repairs to the Chapel amounted to £10 (£1,203.20) and already £40 (£4,812.80)had been collected towards the total amount needed of £55 (£6,617.60).

Before this date in the July of 1856 a proposed testimonial for Dr Spencer was put forward in the Nottinghamshire Guardian which would include a complete anatomical model (described as ‘Azoux’’ model) accompanied by a set of diagrams as a tribute to his work and his popularity. The Duke of Rutland set off the fund with a £15 starter and other notable figures pledged amounts. Dr Spencer was seen as a serious practitioner and respected promoter of his subject, being held in the highest regard and the editor of the paper ‘would be glad to receive any subscriptions that may be sent.’ It is possible that the props of his later lectures including the one at Ilkeston were the fruits of this testimonial.

In 1849 he had made a trip over to Ireland during the famine years and published ‘Life and Death in Ireland’ which exposed the material selfishness in cut-throat competition of the human individual which extends throughout the ages and is as relevant today. He lectured extensively on this subject, appalled at the treatment that human beings could mete out to each other. Of his time in Derbyshire, where he was married for the first time by now, he was living on the Burton Road and attending the Christ Church, describing himself as a ‘Doctor of Medicine and Philosophy and Master of the Liberal Arts’ he published, ‘The Peak and the Plain’ in 1853 and ‘Days in Derbyshire’ followed by other topographical accounts of Malvern, Richmond, and later still, a ‘History of Lytham’ compiled while resident there and on the 1881 census he is resident at 60 Clifton Street in the town. In 1873 he wrote and published, brief biographies in ‘Biographical Sketches of Remarkable People Chiefly from Personal Recollection’ and which is considered his most important work. Friends it seems were as important to him as the natural surroundings of the countryside and his eulogical poem (and printed in a newspaper obituary) to his good friend Thomas Lister would demonstrate just that. By 1878, he published, ‘Pendle Hill and its Surroundings’ just one of the many places with which he made an intimate acquaintance and which demonstrates his love of nature and his ability to write about it.

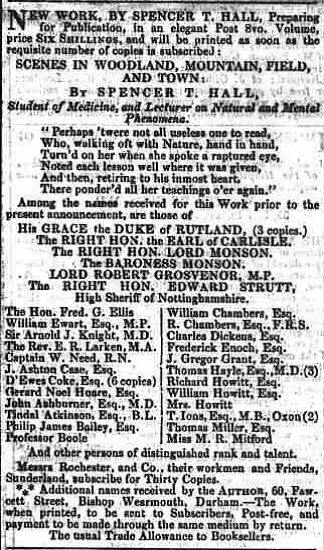

He had lived in several places during his lifetime, and it is a task to chase him around the country via the records. He had travelled regularly around the country and into Scotland, giving lectures, most importantly on mesmerism and was attributed to curing more than one person through this practice. In 1850 the Nottingham Guardian announced that Dr Spencer was to take up a permanent residence in the north when he had accepted the situation of secretary and dispenser to the Homeopathic Institution in Fawcett Street, Sunderland. It is at this time that he publishes ‘Scenes in Woodland Mountain, Field and Town’’.

His final residence after living and practising in several places was the burgeoning seaside resort of Blackpool, where he died and is buried in the municipal cemetery at Layton. While at Burnley where lived previous to his retreat to the coast, he describes himself as a Doctor of Philosophy and a Hydropathic Consultant and before his marriage while in Derbyshire in 1851, he describes himself as a poet and philosophical practitioner. And on the 1861 census return where his living at 53 Normanton Street in Derby, he describes himself as in that longest of all job descriptions, ‘Doctor in Philosophy and Master of the Liberal Arts, University of Lubingen; Doctor of Medicine of the Eclectic Medical College of Cincinnati practising Homeopathy and not registered under the English act of 1850. Also occasionally employed as an Author on Scientific and other subjects.’ Maybe there was a little bit of intellectual conceit in the description or maybe it was his need for accuracy or even of the need for the independence in expression of his need for individuality. The recording officer must have found it interesting enough and worthwhile to write down without precis. A young niece, Mary Oldham, is visiting him at the time which might demonstrate that he wasn’t completely divorced from family ties. He had two sisters, his elder stepsister Hannah and a younger sister Sarah and it was she who had married into the Oldham name. In 1851 a niece Eleanor Oldham had died aged only six years old (though there is an Eleanor who is eight months old on the 1841 census in the family home). In and in the obituary littleEleanor is only the daughter of Thomas Oldham and niece of Samuel Hall, the need to mention the mother, Spencer’s sister, not considered necessary, though the family was living at Brookside Cottage and probably under the same roof as father, grandfather, and father-in-law, Samuel, though they are not there on the 1851 census.

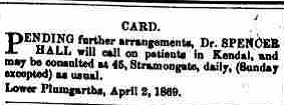

After leaving Lytham for Blackpool, the town next door, he continued to practise as a homeopathic physician though this was not a successful enterprise. His children with his wife, Mary, were born variously in Matlock, Kendal (Plumgarths) and Windermere. It was while at Bowness in 1865, that as an anti-vaxxer, during a smallpox outbreak, that he was fined 15s (75p = £100.26p in 2021) for refusing to allow his one year old child, Samuel Gifford to be vaccinated, citing his own medical point of view in his defence. He was eloquent in his defence and was polite enough not to confront the law through bloody mindedness or conspiracy theory and cited his own medical reasons, which now may be interpreted as a medically derived scepticism of the purity of the vaccine as he had much experience in observing vaccination programmes. He had seen his relatives fall very ill despite having been vaccinated and he himself, had become so ill after vaccination that he nearly died of the smallpox at one time. While accepting the law on vaccination, he entreated the court to believe that he loved his son and would not want to expose him to the dangers that he could clearly see as a medical practitioner. The court accepted his defence in principle but were powerless not to fine him for breaking the law and the 15s 75p; £90.24) fine was sufficient to cover the costs of the case only.

The following year, Dr Hall petitioned Parliament, continuing his argument presented to the magistrates at Bowness, that the vaccines of the day were not pure and could, through an improper understanding, contain more virulent contaminants. His plea was that the increasing stringency of the vaccine programme be paused until a greater understanding of the vaccine was achieved.

It was while at Bowness in 1864 as a homeopathic practitioner, and renting accommodation off Joseph Livesey of Preston, that he was in court again but not as witness to the prosecution as some property had been stolen from the house, a ‘damask table cloth and one plated dessert spoon’. The property was not his but belonged to the landlord. It was when he had interviewed a young girl for the position of maid, and he had given her the job and she was expected to start the following Sunday. However, she had found the time while waiting alone in the kitchen, to steal the items. These were later found at her house and she claimed she had picked them up by mistake and had taken them home. The excuse was considered feeble and she was given one month’s imprisonment at the Kendal House of Correction with hard labour.

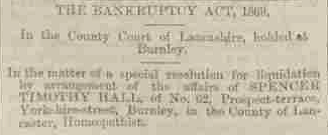

Spencer had been declared bankrupt twice, the first time in 1863 while practising in Derby, the practice of mesmerism being too way-out for the general public to have any confidence in it especially as it was ridiculed by the medical establishment and no doubt patient numbers were few.

If he’d stayed as a newspaper editor or a man of letters he perhaps would have been financially stable for all of his life. As a newspaper editor he wrote about any relevant subject matter and as man of science he contributed to scientific journals and as a man of literature he contributed to that sphere of interest too with equal competence earning the respect of others in the same fields of work. However, his enquiries into the more arcane and least understood aspects of human behaviour and medical condition brought him little financial reward. In 1863 in Derby his bankruptcy was complete when all his possessions ‘except necessary wearing apparel of himself and his family’ were taken away from him and into the possession of his creditors. The second time he was declared bankrupt was in Burnley when in 1880 he was living and practising from No 62 Prospect Terrace when he had incurred liabilities of £250 (£32,000 in 2021). The nature of the liabilities are not known but perhaps refer to rent at least in part.

In 1875 while resident at Burnley he had died ten years ahead of his time, and his obituary was published in London in the ‘Publisher’s Circle’ of that year. The mistake was noticed and corrected that though it was Dr Spencer Hall who was Dr ‘John Spencer’ Hall who had passed away, it was not Dr Spencer Timothy Hall. Dr John Spencer Hall had been the librarian for the Athenian Club in London for forty years and an apology and best wishes for the future were given to the real live Spencer Hall. He had lived in Burnley for the decade between 1870 and 1880 and his bankruptcy of the latter date seems to have convinced him to move on. He did continue lecturing and returned to Sutton to give a lecture on ‘Phrenology, Education and Religion’ in the May of 1879 appropriately given in the new Board school room. In 1880 when Spencer was about to leave Burnley and move, it is assumed then, to Lytham which his next known residence, he agreed to contribute a couple of articles to the Newark Advertiser which had just moved to new premises and had invested in more modern equipment and was proud to state that a lot of its news would now be received by telegraph. In launching the new look Advertiser the status of stories from known celebrities was considered a good move, and Spencer’s contribution included appropriately his ‘Rides and Rambles around Newark.’ He had already in the previous year, contributed his ‘The Trent and its Tributaries’ to the Nottingham and Midlands Daily Express.

To those friends observing him in his later years, he was a man of sorrow and regret and seems to have been overcome with the approaching despair of self-convinced under-achievement and gradually failing health. In these later years of deterioration, the unfulfilled hopes and dreams of being able to pursue his ambitions and provide for his family weighed heavily upon him as the reference to private letters would suggest. In these he rued the distance between friends and missed the vibrant conversation to be had among them, ‘could you not slip over to Blackpool to have a day with us. We should have much to talk about… I feel old tonight and cannot say much in closing, but hope further correspondence soon if you do not come.’ The correspondent to his home at 81 Alexandra Road in the town is not mentioned but he was a friend and correspondent to many men and women of letters and accomplishments, and these friends were worried about the state of his health as his letters spoke of despair and depression and consequently they championed his cause to the Royal Bounty Fund for his’ services to literature’ and though this was a successful plea, and he received the news of the grant of £100 (£13,672.73 in 2021) from this Royal Bounty Fund, endorsed by the Queen in the January of 1885 it was only months before he died in the April. A report claims that he received the grant from the Prime Minister William Gladstone, but it is not clear whether he had actually received it as he died in most abject poverty and it is not certain whether this was awarded to his widow.

The cause he had championed and given his life to had let him down in the end. He was never a man who could achieve lasting material success, driven instead by the need for a spiritual and intellectual concept of truth, and he died at his home in Blackpool on the 26th April 1885 in virtual poverty leaving his wife, now in poor health herself it is claimed, and young children, with no provision. They were left in the hands of the generosity of subscriptions and contributions via the notable names in the town, of the Revs Wayman and Balmer.

His lifelong friend Charles Plumbe provided the headstone for the grave and the epitaph for the gravestone. Charles Plumbe was a printer in Nottinghamshire and became the Registrar of births, marriages and deaths for the Mansfield district. His son had taken over the family printing business by the time of his father’s death in 1899. Charles Plumbe refers nostalgically to his friend in the local paper of 1890 when he speaks of him as someone who made a name for himself wherever he went and that many of the older readers would have known him, or at least have a memory of him. There seems to have been talk of placing a memorial over his birthplace to which Charles was referring in his letter. By then the cottage in which Spencer had been born had been demolished and, though there was empty ground on the spot, he didn’t think that there would be much of a problem seeking permission off the land owner, the Earl of Portland, whose tenants under the Earl’s forefathers were Spencer’s father and own forefathers . Charles remembers Spencer’s earlier leaflet publication of local interest entitled ‘Townroe’s Ruin and Thorp’s Retreat’ which achieved great popularity at the time.

It is perhaps with cherished memories that Charles was returning a favour to Spencer as in 1854 Spencer himself had championed the cause of a Samuel Plumb, who was no doubt relate in some way to Charles. He was a frame knitter who was also an intellectual who had written and contributed poetry and solutions to mathematical problems to the Nottinghamshire papers and mostly anonymously. His work as a frame knitter among adjoining houses of homeworkers in the lace making industry was far removed from the life of a poet and mathematically competent person. Spencer had organised a means of supporting Samuel and suggested that a book of Samuel’s writings and poetry, which had seen the pages of the Nottinghamshire Guardian and other local publications, should be printed and sold for 5s (25p) a copy. Spencer would see to the printing free of charge and other gentlemen literary figures of the district had pledged financial support. His fear was that Samuel would have to be admitted to the Workhouse without this extra financial help. It is perhaps ironic that Spencer’s brother Clipstone was in the Workhouse at this time but it is not known what Spencer’s attitude to, or even knowledge of this fact was or whether his intellectual land literary friends had a higher value than his own brother, or whether there was anything he could do about the situation anyway.

Dr Timothy Spencer Hall had not been forgotten in his home county and from time to time a reminiscence or two appears in the newspapers and he was remembered in Nottinghamshire historical and literary circles after his death. In 1921 the Nottingham Journal records the fact that his works ‘command a good price’ because they have not been reprinted. And in the Nottingham Evening News of June 1933 his historical reference to the Hemlock Stones and the ancient rituals of fire on Mid Summer’s Eve which refer further back to the Celtic Beltane Eve and that Dr Hall, in his description of the time, notes that there are many of the older people in the village or the area who would remember the celebrations. In the Nottingham Journal of January 1932 he is remembered as being one of the ‘forgotten poets’ of the district. And in Arthur Mee’s ‘King’s England’ on publication and reviewed in the Birmingham Gazette of September 1938, he is described, quite accurately, by the author as a ‘jack of all trades’, a man who could, ‘plough and reap, stack and thresh and winnow, make a stocking and a shoe, write a book and print and bind it and cure all sorts of ills’.

In praise of lasting companionship in old age he writes from the Lake District;

They fondly joined at life’s hill-foot,

Resolved to climb together,

Their union lightening every load

And containing every weather.

When fortune smiled upon their way

They shared its sun and flowers,

And sunshine of their own they made

In winter’s chilly hours.

That time went on till he grew grey

And wrinkles her did cover;

But age can never colder make

A true and tender lover;

So they were young until the last

As when in youth they started,

For first impressions ne’er grow old

With those who keep true hearted.

Mary’s Dream. The frailties, and perhaps despair, of being human expressed in depth and that, while you can only do your best in life, ultimate peace, hope and salvation nevertheless lie elsewhere in another world.

MARY’S DREAM

The days are shortening fast, Mary,

The nights are growing cold,

And sadder moans the fitful blast

Along the twilight wold;

Let’s close the shutters tight Mary

And stir the brightening fire,

And thou shalt tell, with warm delight

Old tales that never tire.

~~~~

Yes! Thou shalt conjure up for me

The hopes that once beguiled

Our hearts, when first upon thy knee

Our little angel smiled;

For though that knee, so supple then

Be stiff and weary grown

Ere long, with Him in heaven, ….

Will youth and health be known.

~~~~

Well, I believe it all, dear John,

So come, sit down by me;

How sweet the faith that what has been

Of good will always be;

And doubly sweet to know, dear John,

Our child can no more die –

That I’m “an angel’s mother” here,

Though he’s beyond the sky.

~~~~

I’ll something tell to thee, dear John,

But not a tale of old;

I only learnt it yesternight –

Twas by that angel told!

He hovered near me while I slept

A calm insensate sleep,

Though my soul a happier vigil kept

Than sense could ever keep.

~~~~

And when he spake ‘twas not, dear John

In words like thine and mine

His thoughts flash’d forth in every look

So radiant and divine,

That all the charm of music’s art,

Though not a tone was there;

And O! it overfill’d my heart

With bliss beyond compare.

~~~~

He said that the sky above

Seems heaven and us between,

To angels there and those they love

It does not intervene;

That all they fix their hearts upon,

No space from them can sever,

But what becomes as them as one

Is with them one for ever.

~~~~

That all we realize by love

And faith of heaven and earth,

The means of intercourse will prove

With beings of noble birth,

Till we, to higher natures wed

Are won from this dull sphere,

No more the tear of grief to shed

Of faltering move with fear!

~~~~

And while communing thus be held

My angel child with me –

A glorious vision I beheld

No words can paint to thee

For in a glow of holy light

Far purer than the sun,

The future lived before my sight

And all the past had done!

~~~~

But what to most wond’rous seem’d

In that pure world of light,

Was finding this world there redeem’d

From shadow into light;

The false, like clouds, away had pass’d

From the unchanging blue,

Yet through eternity to last,

The true remain’d the the true.

~~~~

And by that token blest is known

Thy truth, dear John to me

For there I bow’d before the throne

With our sweet babe and thee;

And O! a sweet reward is thine

For all thy love and care,

For here though aged and weak I pine

We both were youthful there!

His name is now revered in his final resting place of Layton Cemetery in Blackpool and commemorated in the guided tours and the literature of the cemetery and this current biography is a contribution to it.

It seems that the script of his funeral card was a quote from a poem of his placed by Charles Plumbe.

In Loving Memory of

SPENCER TIMOTHY HALL

Ph.D., M.D.

Who departed this life April 26th 1885

Aged 72 years

Oh God of Mercy, Love and truth;

Let our whole trust be placed in Thee;

Our guard in childhood, Guide in youth,

Our solace in maturity;

From the beginning to the end

Our father, Saviour, Brother, Friend.

I

His name is now revered in his final resting place of Layton Cemetery in Blackpool and commemorated in the guided tours and the literature of the cemetery and this current biography is a contribution to it.

It seems that the script of his funeral card was a quote from a poem of his placed by Charles Plumbe.

In Loving Memory of

SPENCER TIMOTHY HALL

Ph.D., M.D.

Who departed this life April 26th 1885

Aged 72 years

Oh God of Mercy, Love and truth;

Let our whole trust be placed in Thee;

Our guard in childhood, Guide in youth,

Our solace in maturity;

From the beginning to the end

Our father, Saviour, Brother, Friend.

In 1899 while Blackpool was a popular visiting spot for many people from the industrial landscape of the country, there were many from the Nottinghamshire area and one man (?or woman) from Sutton (in Ashfield), proud of their heritage, forsook the Promenade and instead went to visit the cemetery at Layton to seek out the grave of Dr Spencer Timothy Hall, county compatriot. Whoever it was, transcribed the epitaph and sent in into the ‘Hucknall Star and Advertiser’ on their return. It reads thus and is still visible today though perhaps in need of a little tlc;

Here Rests, Life’s Labour’s O’er

Spencer Timothy Hall Phd MA

The Sherwood Forester

Author of ‘The Forester’s Offering’

‘The Peak and the Plain’

‘Biographical Sketches of Remarkable

People’ etc.

Born in Sutton in Ashfield, 16th December 1812,

Died at Blackpool 26th April 1885.

‘Who, walking oft with nature, hand in hand,

Turned on her when she spoke, a raptured eye

And then retiring in his inmost heart,

There pondered all her teaching o’er again

Until o’erfilled with gratitude and joy,

He tried to echo them in hymns to God,

And cheering words and work for suffering man.’

Erected by his early friend C. P.

From the Shields Daily Gazette of September 1887 written by a correspondent who knew him personally and had some few years previously walked with him in Bronte Country and marvelled at his fitness his energy and his knowledge, ‘A tall, strong manly, simple hearted man was Spencer T Hall, one of those who win reputations, and are capable of vast labours, but who have no talent whatever for succeeding in the worldly sense of that term. He was one of the earliest and most enthusiastic exponents of what are still sometimes called ‘fads’ he took up with homeopathy, with mesmerism, with phrenology, and I know not what besides.’

As for his wife, Mary Julia Hall, a transcription from the MEN 4/12/1916 (obits) shows she survived for thirty years after her husband’s demise and died at the age of 81.

‘Mary Julia Hall, the wife of the late Dr Spencer T Hall. Internment on Thursday at 2.30 pm at St Paul’s Church Kersal.’

The records reveal that she left Blackpool to return to Kendal where she lived with her daughter, Elinore for some time, as the 1891 census return shows. The census returns for 1901 show her living in Cheetham, Manchester along with her daughter Edith and her son, Edward, who is head of household. On both these returns the children are adult and in employment and Mary describes herself as living off her own means, so it is tempting to believe that the £100 from the Royal Bounty Fund did find its way into the Hall household and though it wouldn’t have meant materially very much to Spencer, dying so soon after receiving news of the award, it would have, it would be correct to imagine given him the great satisfaction of seeing his wife and his very young children, who would have not known their father very well, provided for in the future.

There is a Mary J Hall who practised homeopathy in London and lectured around the country largely on female ailments, but it is not Spencer’s wife as suspected in some accounts, as this Mary J Hall hails from Cumberland and studied both in America and France, obtaining an MD from Boston University. By 1894 this eminent physician is described now as Mary J Hall-Williams.

the Friends of Layton cemetery.

QUOTES

‘The visit of such a man as our old friend Dr Spencer T Hall, coming as he does from his comparative retirement of the lake and mountain scenery of Westmoreland, to these busy haunts of men, we do not feel disposed to let pass without a few observations. The ‘Sherwood Forester’ is one of those men who have risen to considerable literary distinction, and large moral influence by persevering labour and self-cultivation, animated by a poetical genius, and ennobled by high and pure religious aspirations.’ The Ulverston Advertiser of February 1865, where the correspondent had attended a lecture of Dr Hall’s in Southampton and quotes the newspaper report to bring to the attention the Doctor’s lecture visit to Ulverston which would include not only mesmerism but also phrenology and physiognomy.

Acknowledgements and further reading.

This information is provided free but lease quote the source if using.

The largest part of the information has come from the newspaper archive, British Library Archive and accessed via Findmypast which has also provided access to census and bmd archives.

Online websites consulted;

https://redrosecollections.lancashire.gov.uk/view-item?i=277829&WINID=1648748736316&fullPage=1

https://www.sueyounghistories.com/2009-05-21-spencer-timothy-hall-1812-1885/

inflation calculator

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator