The Blackpool Sanatorium for Infectious Diseases and the History of the Health of Blackpool.

Edited and extended with a second part June 2024

With thanks to Robert Leach for the cover image.

Inflation figures on all amounts relate to 2023

Brief Summary;

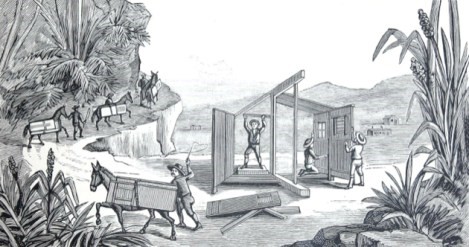

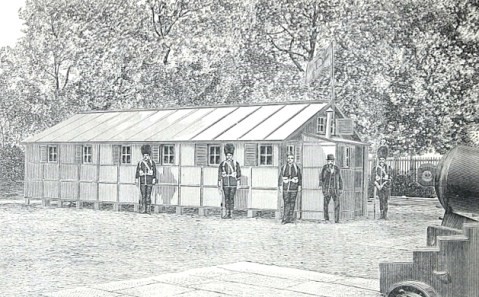

The Sanatorium was first established in 1876 on a site adjoining the cemetery at Layton. It was a wooden building and, though described as having a brick foundation and a slate roof, its detailed construction is unknown. Of a Ducker (Doecker) design, it was a wooden hut of a proprietary German, self-assembly design and, in its less permanent condition, had its problems. Though this concept appeared ideal for non-permanent buildings for use in the field for military purposes, it would not be ideal, it seems, for any serious, permanent function as a municipal hospital. A slate roof would, no doubt, need a brick foundation and perhaps the erection of the Sanatorium in this way, in the newness of its concept, was a careful, or even clumsy, cross between permanence and cost. There was a working association between both the cemetery, next to which it was situated, and the hospital, as the Sanatorium, paid rent for a piece of cemetery land (for an undisclosed purpose – perhaps tenanted to the cemetery), and cemetery registrar John Wray had duties towards the hospital building as did the porter of the hospital, James Robinson, reciprocally towards the cemetery, under the direction, John Wray.

The creation of the hospital arose in the first instance from the growing, and legally defined, responsibilities of townships in the later 19th century to provide hospital accommodation. As an Infectious Diseases Hospital, the Sanatorium had a controversial existence which continued after it had been superseded in 1891 by a more permanent and solidly brick built hospital further up New Road (to be renamed Talbot Road) to the west and which was demolished in 2007. The two hospitals however ran concurrently in function for a while, the original Sanatorium being used for small pox cases until the extensions to the more modern hospital were completed in 1904. The original hut continued with limited use as a hospital, though at least one attempted suicide was taken there to be dealt with, and the building was used later as a mortuary. While the graveyard eventually absorbed the original Sanatorium site, there is still a building in use as a mortuary on the 1910 OS map.

The stories of both hospitals, each preceding the construction of the town’s general, Victoria Hospital, reflect the continuing need to understand disease and its spread, and consequently the need to put into practice measures to prevent, at its worst, the epidemic experiences of the past. Costs had to be borne and legal requirements adhered to, and the medical profession, as well as those municipal representatives in the Council chambers responsible to the ratepayers, and the employed matron and porter on site, had to agree in important areas … and often they didn’t.

The controversy over vaccination and re-vaccination which was contended at the end of the nineteenth century in the age old combat against disease, re-emerges from time to time as different viruses have to be understood and dealt with, both by the medical profession and the local, municipal and national authorities, the latest being the covid pandemic of 2019 and its later variants.

Part 1

Late 1876 to 1900.

There were two sanatoriums – (sanatoria if preferred) –for infectious diseases in Blackpool. The first was constructed, or rather ‘hastily erected’ in 1876 and the second, more substantial, building erected in 1890 and functioning by July 1891. The two ran concurrently, in name and part-purpose for a while, until the eventual demolition of the first, and they echo the continuing struggle to understand disease, its causes, its means of spreading and its consequent control, as townships and populations grew during the later nineteenth century and beyond. This is Blackpool’s story up to the stabilising of the concept of a Sanatorium, in all of its often controversial need, function and physical structure, as the numerous contemporary newspapers reveal it.

On the 19th May of 1871 the Blackpool Board of Health, with chairman, Dr Cocker, met at the Board Room on Market Street to form a Sanitary Committee ‘for the purpose of taking into consideration the advisability of providing a sanatorium, disinfecting rooms &c in connection with contagious diseases’. It appeared to be a topic with a high level of sensitivity and, while the motion was carried without the presence of the press who were asked to leave, it wasn’t a unanimous decision to consider further discussion to that end. There were those who didn’t consider a sanatorium necessary and those who considered that the presence of such an establishment in the town, with the unsavoury title of an ‘infectious diseases’ hospital, would lose the confidence of the visitors upon which its economy depended. These visitors who packed the boarding houses and hotels, might then be wary of coming to a disease infected coastline rather than the town with the reputation of being the healthiest watering place in the land.

However, some years later, those in favour of creating a sanatorium were given a legitimate boost by section 131 of the Public Health Act of 1875 which states, ‘Local authority may provide for the use of the inhabitants of the district, hospitals or temporary places for the reception of the sick.’ The Act also gave Local Authorities more obligation, and indeed powers, to devise necessary bye laws for the consideration of public health. This concerned, among many aspects of the basics in maintaining the health of a town, not only the provision of clean drinking water and the disposal of sewage, but also powers to prosecute and impose fines for breaches of the devised byelaws. While water had been piped from the Bowland Fells since the middle of the century, there were still parts of the town that relied on wells and these could, and did on occasion, become contaminated. There were numerous ash pits for burning rubbish and, while a basic sewerage system had been in place for some time, there were still cess pits and unconnected privies, and for the sewage that didn’t end up in Spen Dyke to eventually reach the sea, the controlled sewage from the sewerage system was deposited at low water mark to return to contaminate the beach and the edible mussel beds underneath the piers. There was too, the continuing question of the many private abattoirs as the blood, at one time before the middle of the century, ran in the streets, and the carcasses hung outside the shops meant that two people were not able to walk abreast. For the growing populations of towns, in order to maintain their health, research and development was in continuous need for the understanding and control of disease.

In the case of accident, before a general hospital was built in the expanding town of Blackpool, the injured would have to travel to Preston. A little later, as the result of the multiple traumas caused by the Poulton rail crash in 1893, the injured were sent to the already established cottage hospitals of Lytham and Fleetwood. It would take that tragic train crash in 1893 to move the authority to hurry forward from its procrastinations to create its first general hospital on Whitegate Drive. From 1876 onwards, the first place of provision to which to isolate the infectious sick, rather than accident or non-infectious conditions from the township, was then the Sanatorium which was established in the following year after the 1875 Act. It was however a pre-fabricated building, ingenious in its concept perhaps, yet not entirely suitable to function as a serious hospital, as it proved in time, and somewhat inconspicuously tucked away at a distance from the main town of Blackpool just outside the graveyard at Layton.

There was, in the beginning, no provision of access for paupers to the Sanatorium in the Act, though it seems that that ‘class’ of people were eventually accepted at the discretion of the local authority to provide a place for them. Those who could not afford a stay at the Sanatorium in Blackpool were left to be dealt with by the Poor Law system already in place and administered by the Fylde Union in Kirkham, and they would be sent to the Workhouse there. For those at the brink of starvation with no food for their children, there were the soup kitchens. By 1891, these were located at three places; the Assembly Rooms on Clifton Street, and on Dean Street and Chapel Street and accommodated over 1,000 needy people in total per day. The kitchens were supported by charitable donations run by members of the Council and there was sufficient funding at that time, it was agreed, at one of the regular meetings. However, in the continuous uncertainty of the availability of this funding, there were calls for the reduction of locations as well as the opening times of just a couple of hours per day at present. When the Church was asked to contribute to the fund, the Rev Wainwright was upset that charity should be considered a municipal responsibility and not the age old and naturally moral responsibility of the Church. If the lay members of the poverty relief group wanted money from the Church collection boxes, then it should admit members of the church onto its board, where seemingly they had been excluded. The problem was that the terms of dealing with a pauper were not always that clear and, in that lack of definition, it was equally unclear as to who should be responsible regarding admission to the Sanatorium. Soup kitchens of course were much easier and cheaper to arrange than medical care. In a meeting of the Fylde Board of Guardians in March of 1879, the case of a young girl in the service of Mr George Bonny was brought up. She had contracted one of the zymotic diseases, those seven deadly diseases of nineteenth century description, though which one was not specified and, as a consequence, a representative of the Fylde Board of Guardians had been contacted who then contacted the Fylde Board who equally did not know what to do. While the discussions as to whose responsibility was continued, she was taken to the Blackpool Sanatorium. A doctor had seen her but it was doubted that the doctor, as a private practitioner, had had any right to interfere in a public arena. It was assumed that her admittance to the Sanatorium had come from the Town Hall clerk at Blackpool. The Fylde Board then agreed to foot the bill, but only if the case of the girl could be proved to be a pauper case. Logical for the administration perhaps but not for those who rely on the system in place and most importantly for those who are ill, so the system was proved to be still in its early stages of development and, if it was regrettable, it still didn’t matter if such if people of reduced social importance were inescapably used as guinea pigs. The young girl was from Shropshire and, described as an orphan, had been only three weeks in service before she became ill. Perhaps she was truly an orphan, or perhaps also she had parents who could not afford to keep her and so she went into service as was the lot of those young girls and women who had no other choice but the streets, and which in some cases of service, proved to be not much better. There is no more information on the girl, whether she survived or succumbed to her illness and died an unloved and lonely death or, if she survived, then what became of her if she was to live the life of an unprivileged young woman at the end of the nineteenth century.

In a triage system that judged first the ability to pay, the question of who qualifies as a pauper or, more than that, who should take responsibility at that time could, and would, produce tragic results which would eventually be used in argument by the Fylde Union against both the status and the efficiency of the Blackpool Sanatorium.

With the creation of the Sanatorium, the urban Authority of Blackpool could reflect upon itself and be proud of the fact that it had been one of the first to take advantage of the Act. This was a fact later acknowledged by the Local Government at Westminster when it was brought into the argument over the complaints of the Fylde Rural Sanitary Authority that the Blackpool Urban Sanitary District was very much in need of a more efficient hospital for infectious diseases than the one it already boasted. The Fylde authority was looking legitimately to its own concerns, that it didn’t want pauper cases sent willy-nilly to the Workhouse which had its own accommodation restrictions regarding lack of space for infectious diseases. In that correspondence between the three parties, the Clerk of the Urban Authority of Blackpool, Henry Parrot May, could write in defence of his town’s responsibilities, ‘The Urban Authority of Blackpool was one of the first to take advantage of the Public Health Act of 1875. In 1876 they erected, upon the most improved principles, a hospital for the reception of persons suffering from infectious diseases and, since its erection, not only the poor, but the wealthy classes have gladly taken advantage of it.’ So there was some discretionary access the poor, the less well off, here it would seem but not for the paupers, those who had no means at all of paying. What he had failed to say was that the Sanatorium was a hastily constructed wooden hut mostly run by less qualified staff and administered by parties, both medical and civil, who were at loggerheads with each other. And of course in the beginning, and at the Council’s legitimate discretion according the Act, paupers did not have to be accepted, which did produce tragic results in at least one recorded instance.

The complaints of the Fylde Rural Authority weren’t however, without reason, as the death of Ellen Meredith reveals. The Medical Office of Health for Blackpool, Dr Leslie Jones, in stating that the cost of a stay at the isolation hospital was between £2 (£196.69; 2023) and £2 10s (£245.86) a week also states that the Blackpool Urban authority had passed a resolution not to take in paupers. ‘That being so’ he is quoted as stating, ‘the pauper patient was sent in a cab to Kirkham’, ie the Workhouse there. This complaint, referring to the death of Ellen Meredith, had arisen in the December 1878 when there had been a recent death of one of these ‘paupers’ at the Workhouse. It was an incident that the Fylde Authority found legitimate complaint in the inadequate provisions of the Sanatorium in Blackpool that the Blackpool Urban Sanitary District felt it could boast about, but when it was the Fylde that felt it had to subsidise its inadequacies. There was also an arrangement between the Workhouse and the Blackpool district to take in ‘imbeciles’, unless they were infectious, in which case, if they could pay, they might find accommodation at the Sanatorium, but it wasn’t specified as to their fate if they were also paupers when discussing the viability of constructing wards for infectious cases at the Kirkham Workhouse in 1885.

It does seem that a sanatorium was created with at least a little compromise as it consisted only of a wooden hut in the middle of nowhere in the remote fields of rural Layton in an area marked out for the new municipal cemetery, a cemetery which was also not considered necessary by some. Not a very salutary view through the window from the bed of a patient to see the graves, watch the burial procedures and listen to the solemn obsequies of the attending cleric, a viewpoint presented by those who would soon want the Sanatorium moved to a more suitable site and consist of a more substantial building, with pleasant, landscaped views more conducive to recovery. The dead did eventually take over the sanatorium site, though not in the fantasy of a zombie apocalypse but more at the hands of the living who buried them, as the cemetery expanded in leaps and bounds in line with an increasing population, and this first and controversial Sanatorium would eventually be taken down and replaced by that encroachment of graves, its function already replaced by a more substantial building a little further up New Road to the west. This new build would last for over a hundred years before its own demise in its demolition in 2007.

In March of 1877 it was resolved at a meeting of the Finance Committee that the Sanatorium Committee pay the Burial Board £5 (£481.59) per annum for use of the land in the cemetery grounds as its borders were contiguous with the cemetery and perhaps had a portion of shared land. It is not clear which piece of ground this referred to nor to its usage, but the longstanding Cemetery Registrar, John Wray, was required to do work on the Sanatorium building and the porter at the Sanatorium too, would be required to work ‘under the direction’ of the cemetery registrar when not required at the Sanatorium. So the two establishments perhaps had a kind of symbiotic relationship in some part. Indeed it could be cruelly surmised with a certain amount of contempt by those opposed, that the Sanatorium was there to provide corpses for the graveyard.

At the very beginning of the establishment of the Sanatorium, the question of how to accommodate pauper patients was discussed. Since everything had to be paid for and paupers couldn’t pay, how then did the both the morality and the responsibility settle in the hands of the municipal authority with a first call to the ratepayers. The first discussion didn’t take place immediately because the Mayor was indisposed, but the problem of finance would exist until resolved in 1912, largely by private national insurance schemes and by 1947 by a state controlled National Health Service until that too became less of an interest in its current concept, to those responsible for its administration. It was at this date too that the idea of constructing a meteorological observatory within the town was mooted, though no decision was evidently possible at the time and the matter was, perhaps conveniently, passed over to the responsibility of the town’s surveyor for discussion at a later date. The weather of course could, in its observation, statistically reveal the incidences of disease and thus assist in its control.

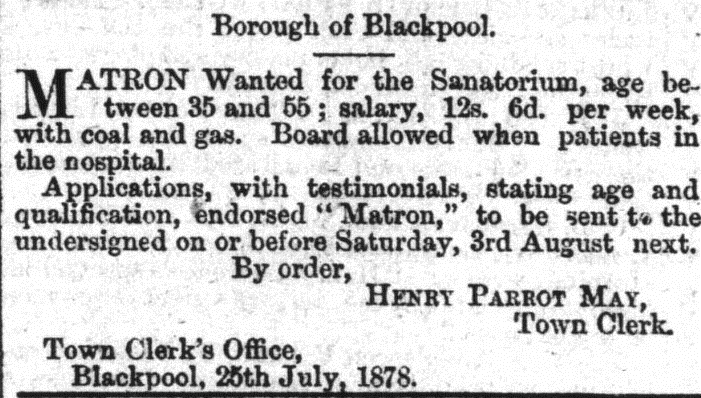

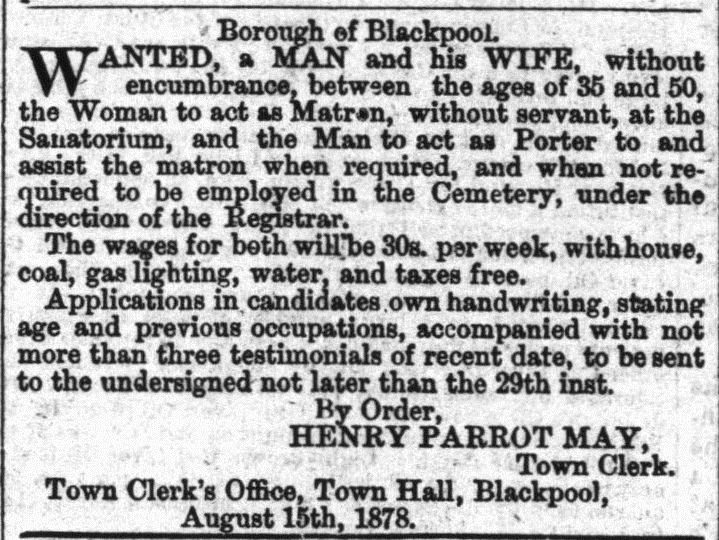

But this new Sanatorium itself had a bumpy start. Only the following year, in the August of 1877 the Matron of the Sanatorium, Mary Ann Priestly, resigned for an undisclosed reason, a fact read out in a letter to the Sanitary Committee meeting of that month. Her resignation was accepted and an advertisement was placed in the Blackpool Herald for a replacement. There are no plans seen to understand the construction of the building nor the provision of detail within, a structure which has been described in its early days as a wooden hut, but its later description as a Ducker hospital has enabled some idea of what it might have been like. It was also resolved at this meeting that the Matron’s role, perhaps in hindsight, had not been clearly defined and that a matron should be provided with a ‘pass book and that she enter all articles required for the Sanatorium in the same.’ So perhaps here again the organisation of the Sanatorium had not yet been established precisely and the Matron’s role was not clearly defined and represented a conflict of expectations and understanding between the medical profession and the non-medical administration that provided funding from the rates. The question of what cost to charge patients for the accommodation had still to be worked out and the August meeting of the Sanitary Committee it was decided that the matron should have that pass book in which the requirements of the Sanatorium could be written down and a weekly charge of 15s (£72.35p) per patient and 10s (£48.23p) for each servant of the rate-paying patient was established. Visitors would be charged £1 (£96.46). Any extras described as aerated waters fowls, fish and preserves would not be included and would have to be paid for, so it was a system of ‘work it out as we go along’ and the matron being in the middle of all this uncertainty perhaps had had enough and had found little option but to resign. At this August meeting the Town Clerk was instructed to chase a Mr Roberts Banks for £3 (£144.70) owed by him for the attendance of a servant during his three week stay. By the end of August the Town Clerk had proffered his resignation. Whether it was anything to do with the confused system that the Sanatorium appeared to represent, is unknown.

But maybe there was another reason for the matron’s resignation and departure. On 7th September 1877 the Sanitary Committee resolved that a stove should be purchased for the Sanatorium and John Wray, in one of his obligations as cemetery registrar, was to be instructed to install it. Perhaps there was a September nip in the air already and the need for heating in the less substantial building that the isolation hospital appeared to be at the time, was considered not only desirable but essential. But anyone with as close an association with it as the matron would have been, would have been well aware of that. The days and the nights can be cool even in the Spring and Summer, but the winter months were approaching and, even if it could be assumed that this stove was a supplementary one, on the other hand, perhaps the lack of one in the first place might have encouraged the former matron to have resigned if such basic facilities were not available to her. Another reason maybe have been that the appointment of a suitably qualified matron was not the forte of the administrating authority at the time as it is later intimated in the appointment of a full qualified matron for the new and improved Sanatorium in 1905.

In March of 1878 the perennial question of what to do with paupers was on the agenda. Infections had to be isolated from the community but those who couldn’t pay constituted the problem of who should take responsibility. There were objections from the Workhouse at Kirkham run by the Fylde Board of Guardians, where the Blackpool Board felt they should be sent so they would not be a burden on the rates, and costs could be shunted over to the Poor Law. But it seemed that a compromise was reached in determining a responsibility. The Blackpool proposal to spread the cost between the two authorities in the case of paupers, appears to be that ordinary cases would be charged at 15s (£73.76) week and the more difficult, smallpox cases 21s (£103.26) for board alone, but this would exclude wines (!), medicines and medical attention, which might be expected to be borne by the Fylde Guardians via the Poor Law.

At the end of June in 1878 the Medical Officer of Health of Blackpool, Leslie H Jones, who had been in the post for five years by now and who had taken over the post from Dr P Hinks Bird, presented his report to the Lancashire and Cheshire branch of the British Medical Association, of which he was president for the year. Held at the Talbot Road Assembly Rooms, he talks about the renown of Blackpool as a health resort where, ‘As far back as a century ago Blackpool was celebrated for the longevity of its inhabitants and its restorative powers as a health resort.’ Quoting the historian, Hutton, Blackpool was a place to which you might be carried to or walk on crutches, but in both cases you would be able to walk back unaided after your stay. There was also the case of a totally blind man who, after bathing in salt water and drinking and treating his eyes with the same, in his six weeks’ stay in the town, found that his ailments had receded and his vision has somewhat miraculously returned. Such was the belief in the curative powers of sea water and a belief to which many a seaside holiday resort today owes its existence. I guess to his credit and that of the medical profession, Dr Jones was not taken in by miraculous cures but rather explained them away in the practical medical language of the day. Fresh air, and often clean drinking water were not available to all in the congested cities, so it not surprising that those few who were able to make the trip to the coast, felt better after indulging in both at the seaside for a short time. From that little fishing hamlet of ‘100 years ago’ where horses were evicted from their barns to create accommodation for visitors and its ‘200 yards of grassed promenade’ it was now an incorporated town of 15,000 inhabitants. From eulogising the nature of the town’s copious and high quality entertainments, Dr Jones then naturally concentrates on the importance of providing the necessary requirements to the health of a town. The main ingredients being a good supply of fresh drinking water, efficient drainage and a properly functioning sewerage system as well as a means of isolating those infectious diseases which potentially constituted the roots of fatal epidemic. The water was piped from the Bowland Fells and drunk unfiltered in many a household, and there had not been a single reported case of illness as a result from this source he claimed. About infectious diseases he suggested that a modification to the Sanatorium might be advisable to accommodate those visitors who, he finds, would be ‘glad to avail themselves of any means placed at their disposal for the removal of their sick relatives from crowded lodging houses.’ Sanitation was a perennial problem with new inventions and methods of dealing with it coming into play in the last part of the nineteenth century. It is interesting to note that regarding sewage disposal there were two outflow pipes at either end of the town, though a town at the time which did not include the districts of North or South Shores or Marton of the present town. Regarding this Dr Jones felt able to claim that, ‘Taking into consideration the great body of water which covers the sands twice in every twenty four hours, a more effective method of disposing of it is hard to imagine.’ A concept which in the progress of time would not be considered valid today with its greater volumes produced and the greater accumulated pollution resulting over time.

And then he goes on to say, after praising the provision of public baths in the town, for those ‘who are not strong enough to bear the shock of ordinary sea bathing on the sands,’ and that there is only one town other than Blackpool, ‘where measures have been adopted for providing every house with an abundant supply of sea water’. Physicians, he agrees with his audience of medical men, ‘know the value of a daily salt water bath for weakly, scrofulous children.’ His praise of Blackpool is easier to quote than precis or re-arrange and continues, ‘I desire finally, to call your attention to our promenade which if report says true, is unequalled in the kingdom; several yards in width, and presenting a level surface, composed of asphalte; it extends a distance of nearly three miles along the coast. It is impossible to exaggerate the great blessing this smooth road by the water’s edge is to invalids, more particularly to those suffering from spinal or uterine complaints for who the jarring of a drive on an ordinary path is so painful and injurious. Here they can enjoy the ride, along a perfectly smooth surface with the sea waves almost touching the wheels of their chairs.’ This statement provides a little insight into the real life experiences of those pictures of the sea side at the time in those old photographs. He goes on, ‘Generally speaking, convalescence form all acute diseases is so well known that I need not dwell upon it.’ For tuberculosis (as phthisis) the doctor claims that many lives had indeed been saved (including his own he claims) by a sea voyage and for that debilitating disease of infant children, tabes mesenterica, itself seemingly related to the tuberculosis bacteria via cow’s milk, Blackpool, as opposed to inland towns, provides a place where children can recover, ‘the abdomen gets smaller, the blood richer and the little patients thrive and grow.’ His description of chorea also has a successful cure at Blackpool for a 16 year old, ‘emanciated’ (emaciated) woman who arrived with no ‘purposive movement’ of her limbs or her tongue and could not speak and had to be carried everywhere. After six weeks of salt water treatment she was able to talk, eat dress and walk and recovered entirely. The point being as the doctor suggested, with all the various diseases which the 120 medical men present would have been entirely familiar with, it was that Blackpool did not have a miracle cure, but possessed the natural advantages of fresh air and provided further facilities away from the smoke ridden industrial towns where recovery was not possible. ‘To conclude then gentlemen, you can recommend Blackpool to your patients as a place where they will find a very equable climate (hotter than London he referred to earlier but without the factual proof, he admitted), extremely tonic air and a well-drained soil – where no matter how great the exhaustion to which sickness may have lowered them, they can avail themselves of the invigorating effects of sea water bathing, and gentle exercise along the coast – and where efficient means are provided for protecting them against insidious attacks from preventable disease – where varied amusements suitable to every taste afford healthy recreation and promote that diversion of thought and relaxation of the mind so valuable as aids in restoring health. Nor will you forget those subtler effects produced by the panoramic changes of scenery, unequalled in magnificence, displayed by the mighty ocean, when lost in all the glories of the setting sun, the wearied tenant forgets for a time the insecurity of its own, “frail dwelling place” and is drawn to thought of immortal life.’ His conclusion was greeted with great applause and while society has changed and medicine advanced in time up to today, the freshness of the air, the expanse of the ocean and the glories of the setting of the sun are now readily recorded in photograph or moving film, and are still relevant and important for all to enjoy today. So it seems that everyone was happy and the meeting broke up and the members visited the various attractions of Blackpool which included the Winter Gardens and Fernery, South Pier, Reads Baths and the Raikes Hall Gardens, concluding with a meal at the Baileys Hotel. Perhaps a good time to be a physician.

In his speech at the meeting, Dr Leslie Jones, referring to the siting of the Sanatorium as its main and vociferous proponent against opposition for its creation in the first place, describes it as having ‘been erected at a convenient distance from the town’, that is by the cemetery grounds a little to the north and east. Here it could be safely hidden well out of the way so that no-one could find fear in the fact that Blackpool could in any way be associated with infectious diseases such as the ever dreaded smallpox (of which there had been no reported cases in the town recently anyway).

Away from the meeting of medical men, in the November of 1878, the Blackpool Herald reports that ‘The Committee recommended that the Surveyor be instructed to repair the approach to the Sanatorium, and that the Matron at the Sanatorium have written instructions as to her duties.’ So it does seem that there is some confusion between what the Committee considers are the duties of the Matron and what the Matron, whoever she might be when appointed, considers to be her duties without interference. Also if the approach to the Sanatorium already needed repairing, it perhaps suggests that the building wasn’t given the highest of importance upon its construction.

The November of 1878 revealed the efforts of the Fylde Board of Guardians to reach an understanding with the Blackpool Corporation regarding ‘the occasional use’ of the Sanatorium for pauper fever patients, but at that time no reply had been received from Blackpool. Paupers were an element of controversy when payment for treatment was essential to keep the Sanatorium financially viable before a morally fairer system, acceptable to all, could be conceived and put in to practice. The December of 1878 revealed those differences between the Blackpool Urban District, the Fylde Rural Authority and the Local Government Board at Westminster when the Fylde Authority, with some justification, it seems, had written to the Government authority to complain about the inadequacies of the Blackpool Sanatorium. This initiated a series of letters in subsequent correspondence between the three parties. The case of the death at the Fylde Union Workhouse involved Ellen Meredith, a young, single girl without a home, and parents in Wrexham who could not be contacted, and who was living rent free, it seems, as an unpaid house servant, at an address in South Shore belonging to a Mr Wright and family. When it was evident that she had contracted a fever, Mr Wright contacted the health authority to remove her to the Sanatorium in Blackpool, but this was declined as she was considered a pauper and so had no means of paying and it seems that Mr Wright, who would be away from his premises out of town, was not willing, able or obliged to pay himself. Her condition deteriorated and the now dying girl was put in a cab and driven the nine miles along the bumpy, country roads to the Workhouse in Kirkham where she died, it would seem not long after her arrival. The Fylde Board complained that, ‘In this particular case it was anything but creditable to the Board of Guardians and to Blackpool that she had to be brought to Kirkham in a dying state.’ In the construction of the Sanatorium, the local authority had passed a resolution not to take in paupers since the cost of taking in a patient was between £2 and £2 10s (£196.69 – £245.86) a week, and that being the case, since the girl or her guardians couldn’t pay then it was natural process to send her to the Workhouse. By 1885 little had improved, in the report of the Fylde Board of Guardians in May of that year it is stated that they, ‘had arrangements with Blackpool to the effect that all cases in the Blackpool District including Marton, should go to the Sanatorium unless they were infectious. In that case they would have to come to the Workhouse.’ The ratepayers of Marton at the time were willing to amalgamate the district with Blackpool for a favourable rate but this didn’t happen till a long time afterwards.

At the same time, and with the inferred resentment of the Fylde in accepting cases from Blackpool when the town should be able to deal with them itself, there was ongoing discussion at the Fylde Union Workhouse, to create a separate, purpose built building or to extend the current building for the purposes of isolating infectious diseases. But to those with any sensitivity or responsibility in their occupations, it was considered grossly wrong for those in Blackpool to deny a place at the Blackpool Sanatorium to those who required it, whatever their financial status. Before a concept of a National Health Service, the cost of staying at the Sanatorium was considered steep, ‘even for the middle classes’ let alone the ‘pauper’ class and it was mooted that could not a lesser fee be payable and some kind of provision be made for those who had no means at all of paying? The case of Ellen Meredith had been brought up in this discussion at the meeting of the Committee of the Fylde Board of Guardians in November and prompted the query to the Board of Local Government in Westminster. The conflict in the question was whether Blackpool should, or would, be able to provide a hospital space for paupers in some form or other rather than relying on the Union Workhouse which claimed the town was quite evidently merely passing the buck while there was the concept of a provision in place in the existence of the Sanatorium.

The death of Ellen Meredith, a poor girl made famous only in the loneliness of her suffering and death, was brought up once more as the subject of this continuing complaint in the following January of 1879 when the Inspector of the Local Health Board complained strongly about the conditions that the Blackpool Urban Sanitary Authority allowed to prevail at the Sanatorium. A letter had been received from the Local Government Board referring to a complaint made by Mr Cane, the Inspector, that the Blackpool Sanatorium did not possess sufficient accommodation, and the building was kept at a cold temperature and it was queried whether it was fit for purpose. The letter advised the Blackpool authority to look more closely to its responsibilities regarding the isolation of infectious diseases. This was received with some surprise by the Sanitary Authority which claimed through the Town Clerk, Henry May, that should the need for more accommodation be deemed necessary then there was enough land owned by the Council on the present site to expand at will and the Blackpool Urban Authority was one of the first authorities to consider the seriousness and need for an isolation hospital in its construction in the first place. That was the retort of the Blackpool Town Clerk, preferring to smother the negative comments beneath a blanket of positive ones as the argument became a game of tennis in the apportioning of responsibilities. In the February of 1879, at a meeting of the Sanitary Improvement and Parliamentary Committee it was resolved that the Medical Officer of Health should be ’empowered to make such additions to the Sanatorium as he may deem necessary for disinfecting purposes.’ So the Sanatorium was evidently still in its early stages of concept and development. The Sanitary Committee still had its own direction despite all, but perhaps was aware that criticism was not too good for the town’s public image and felt that a little improvement should show on the records.

In April of 1879 Blackpool’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr Leslie Jones in his somewhat comprehensive report to the Local Government Board, in speaking of the many topics concerning the health of the 15,000 residents (and the several thousand visitors) of the town at that date, refers to death, differing between classes from upper class to paupers, states that there had been no cases of smallpox, measles, diphtheria, typhus, cholera or puerperal fever. Differentiating the paupers, there had been 40 cases of sickness one of scarlatina and six of enteric fever. These had been removed to the Workhouse where there had been four deaths, two from enteric fever and two from phthisis. Of the Sanatorium four cases of scarlatina had been admitted and all recovered, but of the two cases of enteric fever admitted both had died. It was thus demonstrated as being more beneficial to be admitted to the Sanatorium than to the Workhouse. Those who could afford the fees would perhaps have a better chance of surviving. As all things move naturally in cycles without intervention, we are once more in 2023 approaching a state of Health care in which affordability is more equal to recovery. The report, emphasised the importance of removing cases of infectious disease ‘not only from among the lower but also from among the upper and middle classes of residents and visitors.’ While social classes have been less distinct in 2023, it has been covid that has levelled them all in a contemporary sense and an isolation policy deemed paramount. If it is coughing and sneezing and leaving traces of virus on door handles and such common surfaces during covid which is the understanding of today, it was, added to the ignorance of such, often the overcrowded and inadequately ventilated dwelling and boarding houses in 1879 that would propagate infection. This was exacerbated at the end of the nineteenth century by things like the back up of sewage in the cellars due to the less developed sewerage provision, the non-standardisation of milk and butter production and the lack of provision of isolation and the piles of contaminated rubbish accumulated in the backyards of the built up areas with privies that needed emptying by the night soil men which the sewerage system of more perceivably healthy disposal had not yet reached.

In the general Council meeting of July 1879 it was pointed out that not a single infectious disease had been reported in the month and thus no admissions to the Sanatorium in the same period, so it is not known whether the matron got paid or whether the stipulation regarding non-payment for an empty hospital in the original advert had changed, or whether it was deemed necessary to appoint a matron until the hospital was occupied. It was resolved at this meeting that the Town Clerk, ‘be instructed to write to the medical men of the town, and request them, in case of their sending any patient to the Sanatorium, to send to the porter a certificate that such person is suffering from infectious diseases.’ So the relationship between the ‘medical men’ and the Sanatorium had not yet been clearly and properly established and was still being worked out.

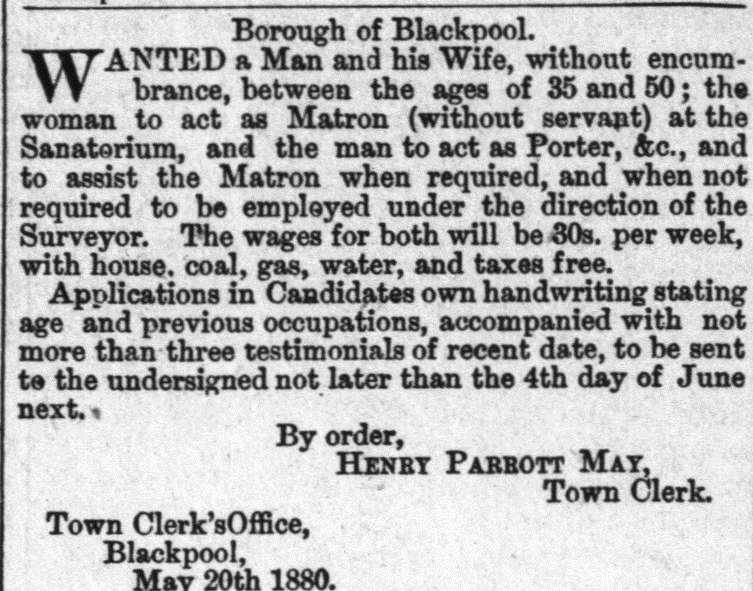

It seems that a matron had not been appointed despite the 1878 advert and a further advert was inserted in the Blackpool Times in the May of 1880. By July, as the subsequent interviews had been undertaken it was decided to appoint Mr and Mrs Robinson as porter and matron of the Sanatorium and ‘in case they do not accept the appointment, that Mr and Mrs Fenton be appointed,’ so there was some doubt about the acceptability of the posts to the first potential appointees and a second line of defence was assured by providing a back-up. The tenure of the matron and porter or ‘master’, as the census return describes the post, of the Sanatorium would see the births of their daughter Edith and their son Herbert, who might have had the unique experience of being born at this earlier Sanatorium if born at home, which it is most probable that they were.

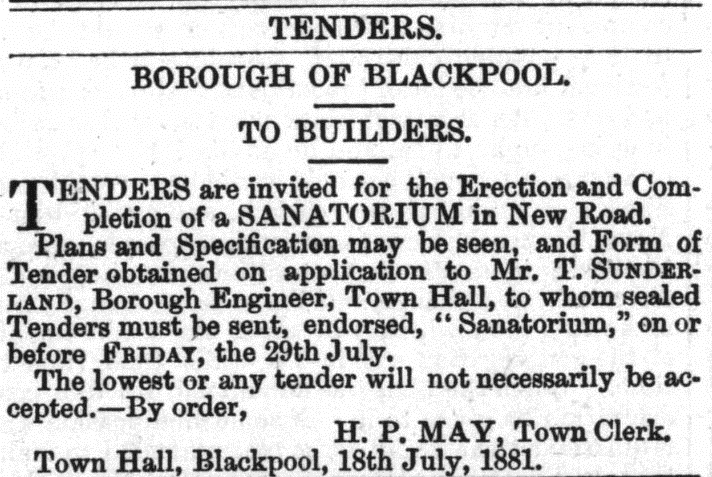

By July 1881 at a meeting of the Sanitary Improvement and Parliamentary Committee in the town, it was resolved that a new hospital be built next to the existing hospital (and ‘contiguous’ with it) and that it should not cost more than £500 (£50,230.69). In a later meeting in the month, on the 30th, the Sanitary Committee, resolved that the erection of a new sanatorium be delayed until a little more research is undertaken and reference is made to other sanatoria to gather relevant information. It was estimated that the building would take five weeks to complete, but that the matter should rest until the end of the season. Five weeks in construction might seem rather a short duration for a building any more substantial than the current one, so that probably represented a mere extension of the standing wooden structure along the lines of the ‘Ducker principle’.

The existing plans did not have the approval of the whole Committee and nothing seems to have come of it at that stage. This appears to be next considered in the December of 1882 when it was suggested by this same committee to apply to the Local Government Board for plans and sections for a new hospital for Infectious Diseases.

1883 Dr Leslie Hudson Jones had resigned his position as Medical Officer of Health and the position was taken over by Dr Welch. Dr Jones had taken up a another post in Cheetham where he was to remain until his retirement in 1911. He had been a Conservative member of the first town council in 1876, representing the Claremont ward. On his resignation he sold his private practice, which he had been allowed to keep, as well earing earning his salary of £100 (£9,849.24) per annum to Dr George Kingsbury.

In March of 1884, while discussions via a sub-Committee to consider the creation of a Cottage Hospital were further deferred, there was also a resolution to transfer the water closet belonging to the house connected to the Sanatorium, which presumably referred to the Matron’s house, to a more suitable place. The Sanatorium Porter had submitted his report to the Sanitary Committee, and perhaps the question of the placement of the water closet was included in that and the committee felt obliged, in agreeing to do something about it. In July of 1884 at the meeting of the Sanitary Improvement and Parliamentary Committee, the salary of the porter and the matron, James and Elizabeth Robinson, of the Sanatorium was increased from 30s to 40s (£154.05-£205.34) a week. By 1884 a Cottage Hospital sub-Committee had been formed to look into the feasibility of creating a general hospital for the town. In a heated debate of July, the question of not only the cost of land to provide a hospital for the town was discussed but also its placement. There was less interest in using the cemetery ground where the existing Sanatorium was situated, and there was more interest in moving it south (from the current town centre hub of that time) to somewhere between Bloomfield Road and Whitegate Drive where land from a Mr Benson offering the land for £150.00 (£15,400.40) a statute acre was proposed, though it was considered that land could be bought cheaper. This site anyway was considered too far from the centre of the town and there was potential conflict with the medical profession of the town who would not want to send their patients that distance to a hospital (though it was also argued by the non-medical men that the doctors had carriages, and it would not take too long to move a patient to a site that was only a few minutes away in such a carriage anyway). The proposal for the new Sanatorium, or indeed for a cottage hospital, was that the cemetery being unsuitable as, in the words of Alderman Hall, ‘they wanted another site, not in the cemetery where everybody was interred, but in a place where they could go about and “see” the fresh air of Blackpool.’ It was evident at this time that, as well as the creation of a cottage hospital, a new Sanatorium was needed as both the site and the building itself was considered inadequate, though there didn’t seem to be the know-how, consensus or urgency at that time to create either a new site or new structure and the search for a suitable site continued to be a protracted one.

In 1885, at the Council meeting in June, while the question of selecting a site for a new Cottage Hospital was once more deferred, it was agreed that the chairman of the Sanitary Committee, Councillor Mycock, and the Medical Officer of Health should see to the provision of furniture as required by the Sanatorium. By 1886 the question of whether to site the new Cottage Hospital in the cemetery grounds was once more subject to controversy and heated debate. While the cemetery site was favoured by some, it was objected by others, the main reason being given that, in a practical sense, a sufficient fall for a sewerage system from the cemetery to the main sewer could not be achieved. If the Sanatorium could be accepted in its position by some, with all its evident inadequacies, then it was implied by others, at this time, that the running of the Sanatorium also could not be as efficient as it should be.

In April 1886 the report of the Medical Officer of Health, now Dr Henry Welch, published his extensive report in which he states that there was only a single case of smallpox in Blackpool and this was brought back from London by a schoolgirl at home for the holidays. She was sent to the Sanatorium where she was re-vaccinated and her family at home also vaccinated. There were 25 cases of Scarlet Fever and five of these were removed to the Sanatorium and the rest isolated at home where a thorough disinfection was carried out and written instructions left. As in the case of measles, the schools were warned of a possible outbreak. In this year there were only two deaths from scarlet fever as opposed to five in 1884. A single case of German measles (Rötheln) was identified and the patient sent to the Sanatorium. In all, cases dealt with by the Sanatorium, constituted the one smallpox, 5 scarlet fever, 7 enteric fever, a single measles and the one German measles. There were eight cases of diphtheria resulting in two deaths. At this time the inadequacy of the Sanatorium was shown up, when an empty school at Queenstown had to be brought into use to accommodate some cases as it was impossible to isolate two particular kinds of diseases at the same time at the Sanatorium. The rental cost of the school to accommodate six patients incurred a very heavy expensive outlay. In all, the medical officer’s annual report showed the reasons for much of the prevalent diseases were due to poor sanitation in the domestic environment, and revealed the medical profession’s attempts to understand and control the spread of these diseases by identifying the causes and dealing with the effects. In this report there is reference to the ‘new’ ambulance and while this turned out to be a rather basic and crude affair it was nevertheless welcomed in excuse, by its usefulness.

There is a rather, critical to sarcastic, comment about this ambulance in the Blackpool Herald of June 1888. It is described as being a rather ‘cosy carriage’ and ‘I’ (the reporter),’suppose the reason why a heavy draught horse is yoked to it and a man is put on the box to drive who is dressed in the picturesque garb of a navvy, is to impress upon the public the fact that cases of a dangerous character are being dealt with,’ as if to tell the world or just the densely packed streets of holidaymakers that the carriage and its passenger(s) were unclean. The origin of the report came from a member of the public on holiday who, in the busy street, asked what the unusual nature of the carriage with the heavy horse and the navvy clad driver (who would more than likely to be the porter of the hospital). The enquirer had to be informed that it was the hospital carriage which was moving an infectious case to the Sanatorium. The reporter then got up on a soap box in the columns of the newspaper to complain of the over obvious nature of the carriage in a busy street full of holiday makers, and the poor reputation that it could bring to the town as a health resort, which should represent a place to get rid of disease and ailments, not a place in which to contract them. It was not a good advert for the town for such a vehicle to be seen driven down the streets which were full of day trippers who, it is insinuated, in their alarm might flee to the railway station to make their way back home as quickly as possible.

In 1886 out of 187 cases reported in total from disease, there were recorded no deaths from smallpox but two each of measles, scarlet fever and diphtheria, 3 from enteric fever and 11 each from both whooping cough and diarrhoea. Whooping cough was a problem because it lay outside the known preventative measures in the understanding of sanitation. The classification of disease contained the seven principal zymotic deaths which are listed as smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, enteric (typhoid) fever, whooping cough and diarrhoea.

In April of 1886, and regarding the prevention of the spread of disease, other than coping with it as the infected person was sent to the Sanatorium, the Medical Inspector of the Local Government Board, Dr Page, had advised that all privies and common ash pits should be exchanged by water closets, and household refuse, as collected in bins, should be removed as both aspects were evident where cases of infectious disease were more numerous. Sewerage systems should also be sufficiently ventilated and regularly flushed. The discharge of sewage into Spen Dyke was considered a particular problem as this travelled through Blackpool and had its outlet by the promenade directly onto the beach. The question of a public slaughterhouse was on the agenda again in the July of 1886. There were many private slaughterhouses in the town which constituted a health hazard, and to regulate and focus the slaughter of animals within a single premises was deemed essential. There were 20 private slaughter houses in number according to the report of the Medical Officer of Health Dr Welch and these should be closed and the town provided with its own, public slaughter house. By July a slaughter house was in function near the gasworks but this meant that cattle had to be taken along the promenade from the railway yard and a more suitable site in New Road, (and owned by a Mrs Barber) opposite the Sanatorium was proposed as having the practical advantage of being next to the railway. In the report, the inadequacy of the Infectious Diseases hospital was also pointed out and the resolution of this should be considered as soon as possible. Discussions for the construction of a Cottage Hospital continued or, in the words of Alderman Cocker, the topic had since been ‘kicked about like football’ in the Council chambers. It had first been introduced in 1885 and the first site suggested in that year was as an extension within the Sanatorium grounds. The proposal in July of this year of 1886 was a site ‘on the southerly side of Dyke’s Lane’ owned by the Clifton Trustees after the previous suggestion of land ‘between Bloomfield and Whitegate Lane’ had been deemed too far from the centre of the town.

In this respect, by July 1886 the site of the ‘present Cottage Hospital’ be used for the erection of an ‘improved’ Cottage Hospital and plans for the same be approved. At the same Sanitary Committee meeting a Mrs Sharp was praised for her donation of 50 copies of the ‘London Weekly News’ to the Sanatorium. So it seems that the ‘cottage hospital referred to, if not mis-described, was the Sanatorium as the general ‘cottage hospital’, as the Victoria Hospital wasn’t opened until 1894. ‘Sanatorium’ as a descriptive word in its dictionary definition could refer (and was on occasion) to the hospital for infectious diseases, a general cottage hospital for accident or non-contagious illness, or the promenade of the town and the town itself each in their function as health giving or convalescent places.

Regarding infectious diseases, there are many tragic cases of deaths behind the closed doors of history that the individual human being has had to contend with in the normal course of a life. Occasionally a case, in the acute drama of its tragedy, can come to light via the newspapers and such a case occurred in the December of 1892 at Breedy Butts farm in Thornton and which continued to Breck Farm in Poulton in which a family were virtually wiped out by diphtheria. Of the Ashton family at Breedy Butts, first the parents had died, and then the children were taken to Breck farm in Poulton, the home of their grandfather, who had died the previous week. Some of these children also succumbed to the illness and died one by one, despite efforts at adoption from those compassionate enough to look after the surviving children for the short time they would be in their care. Three children survived at the time of the report though one was critically ill. It is not known what happened to the other two orphaned children or whether the critically ill child survived. In an attempt to understand and control the spread of the disease the Medical Officer of Health ordered an inspection of the two farmsteads and disconnected the milk supply, contaminated milk being a noted source of infection. Other cases of diphtheria in the district could be traced to Breedy Butts farm as the place of origin. And it is later noted and published that the farm is owned by a Mrs Hardman of South Shore in which case the Ashton family would be tenant farmers there. By January 27th of 1893, as a real and practical tragedy of the epidemic, the farming equipment and produce was up for auction followed, a couple of days later, by the cattle and horses. The farm was taken over by a Mr Christopher Riley who made some improvement before moving in.

At this time too, in the April of 1886, it is recorded that the hospital had been occupied by patients during 251 days of the year at a cost of £27 14s 3d (over £2,899.52) while fees received from paying patients and from the Poor Law Guardians amounted to £42 12s 8d (a little more than £4,510.37.) It seems then that by this time, those who were not able to pay a part, or any part of the fees, necessary for a stay at the hospital could have access through the Poor Law system or maybe even the rates.

In the same month, and on a lighter note of April 1886, the Sanatorium porter Mr Robinson saw a couple swallows at the cemetery which was considered newsworthy enough to be included in the Blackpool Herald and the editor to remark, while understanding that it does not make a Summer, and perhaps with a little intended irony ‘Swallows it seems, know how to appreciate the cheerful surroundings of the town’s hospital,’ no doubt as they fly around the gravestones.

By the end of 1887 it was suggested by the Sanitary Committee that the plans for additional wards to be constructed on the east side of the present Sanatorium be approved. The Sanatorium however continued to be controversial, as it had been almost from the moment of its evidently somewhat hasty and somewhat perceivably ill-considered arrangement and construction.

In January 1888 at the council meeting to accept the resignation of William Jones as the Assistant Inspector of Nuisances and appoint in his place William Cardwell, currently Inspector of Buildings, it was also agreed to appoint Wilfrid Jones as a clerk to the Sanitary department at a wage of 5s (25p; £26.89) a week. On Thursday January 12th 1888 however, the dominating question regarding the ongoing controversy over the status and siting of the Sanatorium came to a head. At a meeting of ratepayers which included many influential property owners and members of the church and medical profession, convened at the Prince of Wales Theatre in order to condemn the siting of the hastily constructed Sanatorium in its placement immediately adjacent to the cemetery grounds, and to the inadequate amount of £500 (£53,694.87) proposed to be spent on extending and improving the present building, described as a wooden hut and no more than a barn, while its facilities were not conducive to comfort or recovery of patients. Insufficient ‘to raise their drooping spirits’, as it was described in heated and sometimes mutually insulting exchanges across the room. It was also suggested that another site, were it to cost as much as £5,000 (£536,948.73), should be discussed by the Council and ratepayers as it could only be good for the town’s reputation as a health resort. The first to speak was the Rev Wayman followed by Rev Wainwright who were both strong in their condemnation of the present hospital and siting. Dr Wartenburg (the same Dr Wartenburg who had provided several magazines to the patients at the Sanatorium June 1886 and no doubt at other dates too) who followed, claimed that he visited a patient recently when the temperature was only 40 degrees (which if he is talking Fahrenheit, is only a little more than 4 degrees Celsius) and should not other suitable sites be considered? Better to have a hospital of which the town could be proud and the visitor confident, and that a proper facility would be available to them should they be unfortunate enough to fall ill. He claimed the currently considered site was eight feet below the present site and was not fit, it its marshy state, for a dwelling house nor a hospital. If any member of the Council in favour of the current site were themselves unfortunate enough to have to spend time in the hospital, they would come out after their stay and immediately propose the construction of a new hospital on an entirely different and more suitable site and find sufficient funds to do so.

While the cemetery was indeed a morbid place, it was nevertheless the only planted public open space in the town and, in its greenery and peacefulness, it was a magnet for many a quiet stroll or ‘promenade’ in the description of the day, in the town and indeed for visitors, and lauded even in the regional press of the nation. An extension to the argument was that the Council could not force anyone to go to the Sanatorium, even if they should make it more attractive for voluntary admission. The only powers it had were to compulsorily send those infected off a ship or from a common boarding house, but no legal powers to force anyone from a private dwelling to be admitted. Of 93 infectious diseases identified only 13 had been treated at the hospital, and those who declined a stay at the hospital stated the reason being that it was so close to the cemetery. The doctors of the town themselves had stopped sending patients there. It would be better to spend £3,000 (£322,169.24), as proposed costs differed in different viewpoints and understandings, on a new hospital on a new site where visitors could feel confident of the town as a notable health resort.

Ultimately it was decided to explore the viability of another site, as it was at last generally agreed among some parties that the present site was considered unsuitable. Since Alderman Grime was at the meeting, as editor of the newspaper he would have first-hand knowledge of proceedings and an editorial column of the Blackpool Herald of 20th January, not only the siting next the cemetery but also the attitude of the Council to the Sanatorium was strongly called into question. The Sanatorium was a wooden hut, hurriedly built in a panic, next to the cemetery and the very fact that it was next to the cemetery made it a least desirable place for anyone suffering from serious diseases to feel comfortable within. While the Council in its desire to save money on the building and its facilities, the ratepayers would demand an improved structure or a different building in a more suitable setting. The Council would argue that £500 (£53,694.87) was sufficient for improvement and an extension to the present building, and to seek another site would mean buying up land at what was considered as large amounts of money ill spent. The need for the publicity of the town which wanted to regard itself as the healthiest place in the land, meant that anyone on the side of publicity alone, and to protect their own interests, would want a sanatorium with the title of an infectious diseases hospital to be set aside well out of the sight and sound of anyone wanting to visit the town. The conflict then was between the good name of the town, with those who felt a responsibility for maintaining that financially lucrative reputation, and the poor patient who succumbed to disease championed by those who had a compassion for the sick in a moral and a practical sense and with a profession or a vocation to tend to them.

The annual Council finance report of March this year of 1888 reveals the annual salaries of the Council employees. That of the Medical officer Dr Welch as £250, (£26,847.44), James and Elizabeth Robinson as the porter and matron of the Sanatorium with house, rates, coal and gas free, each as £104 (£11,168.53).

In August of 1888 when the rates for the Borough were determined, the costs for the Sanatorium included ‘materials and appliances’ were estimated at £210 (£22,551.85) and specific Sanatorium expense including a ‘new ducker’s hospital’. The cost of the new Sanatorium was given as between £3,000 and £4,000 (£322,169.24 – £429,558.98) as an estimated cost, but at this stage it wasn’t yet established to be included in the estimation of the levy of the rates for the following year. By June however, it had been decided to apply to the Local Government Board for sanction to borrow two amounts of £850 and £2,000 for a term of 30 years. Each amount respectively in today’s values of £91,416.82 and £215,098.40.

In September of 1888 at the Council meeting, it was resolved that the Medical Officer of Health and the Borough surveyor, along with the architectural departments get together to discuss the proposed Infectious Hospital building. It was resolved that the Borough Surveyor should be instructed to lay a drainage pipe from land east of the Sanatorium to take away the surface water. This is likely to refer to the proposed Sanatorium as there had been a complaint from local resident and property owner Mr Coulston, though it seems that there had been a drainage problem at the current Sanatorium from the beginning. Meanwhile also in the same September of 1888 the Sanitary Committee decided to distribute the purchases of provisions among several tradesmen for one week at a time, perhaps to get the best price from competition among them all. At the same meeting it was also decided to allow both the matron and the porter of the hospital a month’s holiday, though not specified in the report whether this be an annual entitlement or gardening leave, as talks about the proposed new hospital proceeded more positively. It is also alluded to the fact that there was not much to do at the Sanatorium ‘which speaks well for the sparse demands made on that establishment’ (Blackpool Herald 5th October 1888). In the annual report of the Medical Officer of Health, he states that only 22 persons were admitted to the hospital in 1887 and the average stay was 29 days so evidently not a lot of work for either matron or porter to undertake.

In the January of 1889 there is a complaint to the editor of the Blackpool Herald regarding the general health of the town, about the smell arising from the carting of vegetable matter from the south to the north of the town. It was evidently the case that there was a great north/south divide between the wealthy south and the more impoverished north. Why should the north be afforded the discarded decaying organic matter of the south where the smells prevent the opening of windows? The correspondent cites a case where a whole family had to be taken to the Sanatorium suffering from scarlatina which, he claims, arose from the careless distribution of rotting organic matter to the district. While understanding that the Sanatorium is of inadequate size and hinting at complaint, he suggests that burning such rubbish in home fires could obviate the need to throw it out to rot on its own and, anyway, potato peelings especially make a good warm fire. In the case of a serious outbreak of smallpox in Yorkshire recently, very high prices were paid for shoe leather parings which when burnt gave off odorous fumes which were believed to be a disinfectant. The correspondent signs off as, ‘One Who Loves The Pure Fresh Air of Blackpool,’ who in the anonymity of the name is probably a male though could be female as less notice would probably have been taken of a female at the time if signed as a female.

In March of 1889, and perhaps as result of the strong and vociferous complaints in January, there was a Government Enquiry regarding an application for more borrowing powers for the Corporation, and held by a Local Government Board Inspector. Included in this was an amount of £3,860 (£409,813.91) for the construction of an Infectious Diseases Hospital. This amount included £850 (£91,281.28) for the purchase of land and the rest for the construction of the hospital and the laying out of the grounds etc. The need for the new hospital was justified by the fact that the current hospital was insufficient and could only accommodate a single disease at a time with any efficiency. It was disclosed at this point that for the last 12 to 18 months a separate building had been purchased by the Council to accommodate any extra need, and was used as a nurses’ home when vacant. This extra hospital, the location of which is not revealed, unless an extension to the Sanatorium by the graveyard, had been provided under the ‘Ducker principle’. This Ducker principle was that the building would have been in the nature of a pre-fabricated and, in some cases even portable, building and which could be erected without too much skill needed from the ‘flat pack’ principle. (Ref Historic hospitals which gives an excellent view into what the original sanatorium might have looked like).

As it had now been decided to build a new Sanatorium, the proposed purchase of the land for the new building from the Guardians of Bispham Endowed School would cost more specifically £788 8s 9d (a little more than £84,623.12) was discussed. The exact measurement of the plot of land is described as 2 acres, 2 roods and 20½ perches, obscure measurements which used to have a place on the back of school books of days gone by. The advantages of the site were that it was not too far from a central position for the town, was in a lightly populated area, and was near to both a water supply and sewerage facilities. The building would consist of an administrative block, two separate hospital buildings, one for ten beds and a double hospital ward for five beds with the ‘usual out buildings and ground with a fence round it’. The cost of the building would be £2,323 8s 6d (a little more than £246,631.53) and the grounds and fence etc. would make £3,000 (£318,508.22) a reasonably accurately estimated cost. The hospital would also contain a small dispensary for drugs. There was still objection to the cost from some quarters concerning the suitability of the land and the purchase price which some considered that another site could be bought for less, so the argument of the construction of the hospital on that site had never been a straightforward one and continued to be controversial. Some considered that the hospital would be too big for the size of the population of the town which was estimated at 20,000 at the time. And there were objections to the site from outside the Corporation as the Corporation received a solicitor’s letter threatening legal action against it by two private parties. In perhaps a nimby-pimby way, a Mrs Pickup and a Mr William Wildman complained of the construction of the hospital going ahead on that site which it can be assumed was close to their properties. Perhaps in the light of this, if the complaint was seen to be real and legitimate, the Council at the same time resolved to ‘remove any obstructions to the flow of sewage through the sewer manholes.’

But there were other issues away from the heated argument over the status of the infectious diseases hospital. In March of this year of 1889, the discussions concerning the health of the town were first about whether or not to contract out the removal of night soil at a cheaper rate than the Council could do it, but with the concern that it might not be done efficiently when the health and reputation of the town was at stake. Regarding then the Sanatorium, it had been further resolved to discard any proposal to extend the current Sanatorium and instead consider 2½ acres of land south of New Road and near Boon Ley (in Layton) which had been offered by the trustees of Bispham Endowed School at £300 (£32,216.92) an acre and would cost £850 (£91,281.28) for which a loan would need sanctioning. The total cost of the construction of the new Sanatorium, to include the provision of surrounding, boundary walls etc. should not exceed £2,000 (£214,779.49). In May, the Sanitary Committee resolved that the plans for the Infectious Diseases Hospital, submitted by the Medical Officer and the Borough Surveyor be approved. These plans consisted of an ‘administrative cottage, two pavilion hospital blocks, disinfecting room, wash-house, mortuary and ambulance shed.’ The site chosen was that earlier decided on New Road near Boon Ley and the cost was to be referred to the finance Committee for the purposes of sanctioning a loan of £3,000 (£322,169.24) to cover not only the construction of the hospital buildings but also roads, drainage, boundary walls, disinfecting apparatus and the planting of the grounds. A sub-Committee was authorised to inspect the plans and to make any adjustments considered necessary to the details. By October, the Charity Commission had given the governors of Bispham Endowed School the necessary permission to sell the land to Blackpool Corporation for the building of the Infectious Diseases Hospital.

The birth rate for the town with an estimated population of over 20,000 had lowered each year for a few years and in 1889 was at its lowest. The death rate was given as 15.6 per 1,000 and death by disease recorded as with whooping cough and diarrhoea showing a decrease, but from diphtheria and enteric a fever, an increase. The water supplied to consumers by the Fylde Water Company was of good quality but would need constant assessment to keep it clean. The rates levied for the coming year were set at 3½d in the pound which included a cost £272 (£28,920.96) for the Sanatorium staff and among other necessities for keeping the town clean and hygienic, and in order to save the streets being used as a place to relieve the bladder, £799.00 (£84,955.31) for urinals to include new ones at Central Beach.

In March of 1890 the problematical nature of the new site continued. At the meeting of the Sanitary Committee it was considered purchasing further land at the north east corner of the hospital site which belonged to Messrs. Cardwell and Coulston and which had been offered earlier before the present site had been purchased. It was proposed to buy this north east corner of New Road and Boon Hey Lane at a cost of £168 1s 6d ( a little more than £17,836.46), which contained Boon Hey Lane where it was also proposed to widen the road. This proposed purchase was subject to much heated discussion in the Council Chamber. Why all of a sudden it had been seen necessary to purchase the land now when it was not considered necessary before, and the proposed road to be constructed there would greatly benefit the sellers and their building estate on Boon Hey Lane more than the benefit to the hospital where a road would nevertheless be necessary. The motion, it seems was carried to purchase the land in the face of any objection given.

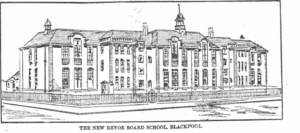

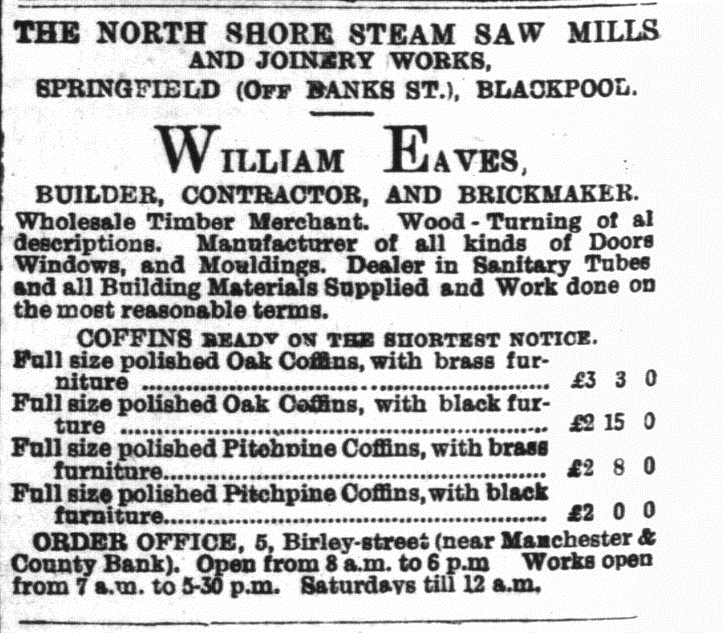

In June of this year at the town Hall of the North Western Branch of the Society of the Medical Officers of Health, the main subject was ‘The increase in Cancer and its causes.’ After the meeting the ‘gentlemen’ as described, as there were no women mentioned, made a visit to the new Sanatorium. In July of 1890, while the new hospital was being built, it was recommended that the Sanitary Committee should inspect the work in progress. There was also the continuing problem of Mr Eaves’ brickworks where bricks, naturally in the process of manufacture, were being burnt, and the smoke arising from this affected the health of the hospital. The land for this new hospital is close to that of William Eaves’ brickworks a little north over the railway (1901 OS map) and the Sanitary Committee resolved that, ‘if any bricks or tiles be burnt on land in close proximity to the hospital, legal proceedings will be instituted’. It seems that Mr Eaves had repeated the burning of bricks since the letter sent to him, and the Committee decided on a final warning. A similar problem would arise at the building of the new Council school at Revoe the following decade which was in close proximity to the brickworks of Cartmell Bros. The brickworks would be eventually bought out by the railway company and William Eaves moved his works to Marton, but before that, there was a compromise or a kiss and make-up between the Council William Eaves, builder of many a structure and an abundance of housing in the town including the new town hall, resigned his position as ward councillor so he could take on the contract for the Sanatorium which was then awarded to his firm.

On a different topic at the same meeting, it was suggested that an assistant to the matron at the Sanatorium be appointed for the summer. This is either for the currently active Sanatorium by the cemetery or in expectation of the opening and functioning of the new hospital.

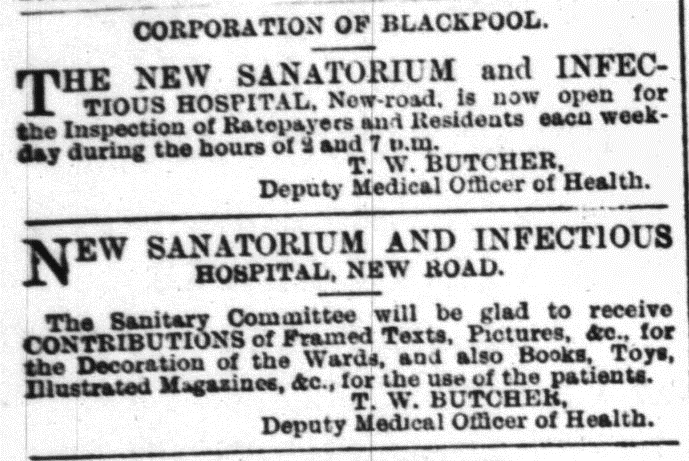

In June of this year there is reference to the ‘new sanatorium’ in the brief report of a meeting of the North Western branch of the Medical Officers of Health who would visit this new sanatorium as part of the meeting, so it had been at least part built by then.

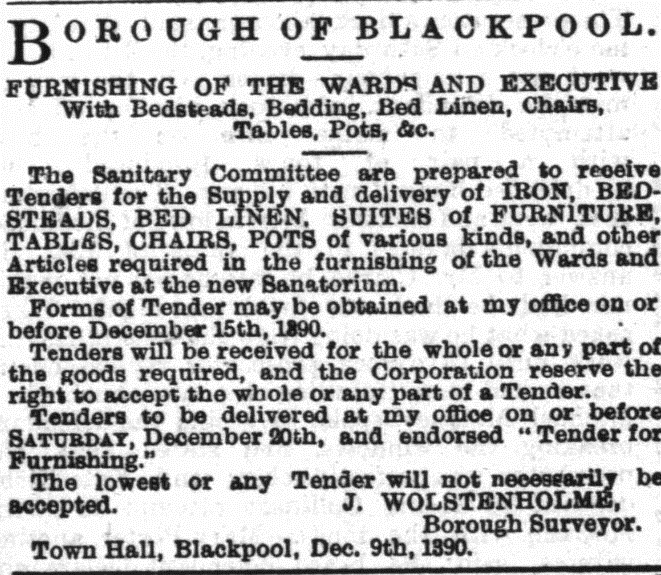

In the December of this year, the cost of its construction came up in a meeting of the Sanitary Committee. Here, two Council members were appointed as a sub-committee to arrange for the provision of furniture for the ‘new hospital’, with a view to a completion in sight and no doubt resulted in the advert above. Regarding the construction, there were questions in the Council Chamber later on regarding how much more cost over and above the loan of £3,850 (£408,752.22) that had already been set out by the Local Government Board, as if the cost was a sensitive subject and questions were not welcome by those present who were interested in answers. Land for the new Sanatorium had previously been offered by Councillor Cardwell at cost, but the profitability arising from this potential self-interest was equally questioned and equally denied in the chamber. There was an added problem that residents in nearby properties had no desire whatsoever to have a sanatorium on their doorstep and when building had commenced during the year, the Council received many threatening letters. But these came to nothing, and in December 1890, the Blackpool Herald of 24th of the month reports that, ‘The furnishing of the of the new sanatorium was begun on Monday; and I understand that before long the handsome structure will be ready to fulfil its functions, though all the same I sincerely trust it will be a long time before it receives any occupants.’ And we all hope in the present day as the covid still lingers that it will at last recede and, like the hopes of the Blackpool Herald in its day, the current hospitals will not receive many more occupants from the virus. But the problems for the Sanatorium were not over as there was an (unidentified) ‘nuisance’ on land near the hospital, the responsibility of a Mr Wiggins to resolve and remove. The question of whether to engage an assistant to the matron at the currently working Sanatorium was referred to the Chairman and the Medical Officer of Health for a decision. So the question of the administrative structure of the Sanatorium was an ongoing feature of discussion.

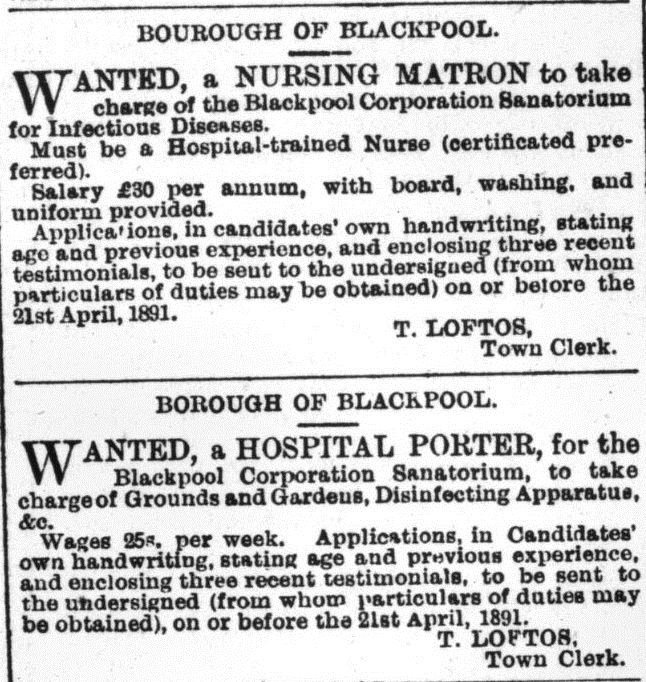

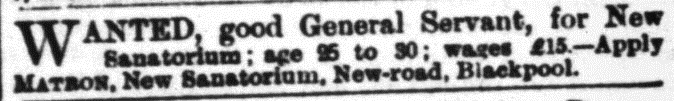

In the December of 1890 the Council officially adopted the terms of the ‘Infectious Disease (Prevention) Act of that year, though two exceptions were specified, sections 22 and 23, and to come into operation on the first day of January 1891. On the 10th April-1891 as the hospital drew closer to reality, an advert was placed in the wanted columns for a matron and a porter for the hospital.