More Names and Stories from Blackpool’s History

Pioneering surgeon, Dr Charles Clay; Blackpool’s first Chief Constable John Dereham; tramway engineers John and Angus Cameron; Alice Ashworth, last landlady of the original Gynn Hotel.

Dr Charles Clay

Eminent physician, surgeon and gynaecologist who worked in Manchester at St Mary’s Hospital in Piccadilly for about 45 years. He retired first to Blackpool then to Poulton where he died after a long career on 19th September 1893 at 92 years of age and is buried in Layton cemetery, Blackpool (on the 22nd of the month). He was one of the high profile surgeons of the 19th century involved in the controversy of the developing art and skills of surgery which included the condemnation or justification of vivisection on animals to improve techniques and success rates.

He was born on 27th December 1801, in Bredbury, near Stockport, Cheshire. His first wife and his children from this marriage in Ashton under Lyne, reportedly died young and he remarried in Suffolk in 1839 to Maria Boreham from Haverhill in Risbridge. Maria lived into her eighties and died in Blackpool in 1885 and she and Charles share the same grave. On the 1851 census return they have a daughter Emily and a son, Arthur B, aged 10 and 8 respectively, and both born in Manchester. These children, to date, have not been traced.

Charles first trained in medicine under obstetrician Joseph Kinder Wood at what is now St Mary’s Hospital in Manchester (where he would eventually become medical officer in 1859). After two years in Edinburgh he moved to Ashton under Lyne from where, in 1839, the same year as his second marriage, he moved to Manchester setting up in Piccadilly.

He had begun operating in 1842 and, from this year, eventually became known as the father of surgical oviarotomy or, ‘the first great Apostle of Oviarotomy’, and was renowned throughout Europe and beyond. In the evolution of surgical techniques he became embroiled in the controversy over vivisection and took the stand of anti-vivisectionist. His various writings and extensive collections of books and of his various interests, which included numismatics, geology and archaeology, were distributed after his death, some of his own writing being available at University of Manchester library and those of his collections elsewhere.

He was a member of a number of societies and it was in March of 1842 that he was encouraged to apply for the post of physician at the ‘Manchester Royal Infirmary, Dispensary, Lunatic Hospital and Asylum’ due to the death of incumbent Dr Pendlebury, but it was too late to put in an application as most votes from the trustees had been allocated to their chosen candidates. He did however promise to offer his candidacy if a future opportunity arose.

Away from several brief, biographies which can be found online, insights into the course of his career can be obtained from the newspapers where his credit for oviarotomy and his stance on anti-vivisection are largely connected with his conflict with Dr Thomas Spencer Wells and those who would argue for him, and those would argue against him. Perhaps ultimately, on the development of successful surgery techniques, those who survived or died on the operating table, whether they be the lower animals or the higher animal status of human being, are the real heroes, as few have a name to extend their contribution to the success of medical science to posterity.

So he is quoted variously as ‘To Dr Charles Clay, of Manchester, belongs the honour of having first introduced into surgical practice, the operation of oviarotomy. Through a long series of difficulties and discouragements he has given the medical profession an example of perseverance and assiduity in the pursuit of surgical science which few have equalled and certainly none have surpassed.’ (Dr John Bowie of Edinburgh as quoted in the Bristol Mercury March 6th 1895.) Or in 1849 he is accredited with, ‘The operation is yours now; no one can rob you of your claim. Call it oviarotomy, not peritoneal section; your success is brilliant.’ He had introduced the operation in 1842 and which excited worldwide curiosity at the time. Even in 1880 in a reflective publication on correspondence between the combatants of vivisection and anti-vivisection, he was called the ‘Great Apostle of Oviarotomy in this Country’. Dr Thomas Spencer Wells took on the role of gynaecologist and received the plaudits for such, though Dr Charles was one of the earlier pioneers. While Charles Clay himself claimed a 75% success rate out of 400 operations it is Dr Wells who is commended for saving the lives of hundreds of women ‘and the amount of suffering that has been saved to women by his means is almost impossible to estimate’. (The Gentlewoman Sep 9th 1891).

Dr Clay had also performed, after initial failure, the first successful hysterectomy and, though both the first oviarotomy and hysterectomy operations can be attributed to American surgeons, Dr Clay’s operations of each were most certainly the first in Europe. The patient of his first successful hysterectomy unfortunately died in an unrelated accident shortly after so longevity couldn’t be proven, and the credit thus went to the American surgeon. The first oviarotomy had been carried out in America as early as 1809.

Surgical practice was often new and experimental, and invited much controversy. How much compassion was shown to the patient or how much conflict or jealousy there was within the medical profession by the practitioners to achieve results is revealed as interpretation in the discussions available in the newspapers. They were early days regarding techniques and operations, even on the brain, could be claimed to have been successfully carried out without anaesthetics. Chloroform was popularised as an anaesthetic only when it was used for Queen Victoria during the birth of one her children.

The controversy over vivisection raged throughout the nineteenth century as the art and science of surgery evolved. As an anti-vivisectionist, Charles was in conflict with those who practised vivisection which included the eminent Dr Thomas Spencer Wells, and there was heated correspondence on the subject throughout the medical fraternity and beyond. While Dr Clay claimed that vivisection had no value in the developing art of surgery on humans, Dr Wells claimed that it did, and the argument wouldn’t go away in the continuing attempt to establish a moral standard. The need for the use of animals to further the knowledge of surgery to save a human life was conducted in highly technical language with one surgeon or observer claiming and counter claiming another throughout this period. One claim was that surgery had been successfully carried out without anaesthetics and without the need to use animals as a first option of experimentation.

When the vivisection argument appeared in the newspapers, as it frequently did, the names of Dr Charles Cay and Dr Thomas Wells usually feature as the argument extended into moral values and those of the church would argue, by quoting the Christian bible, in God’s words, ‘All the beasts of the forest are mine, and so are the cattle on a thousand hills.’ Perhaps those who quoted this were also vegetarians as was the argument used against those who conducted a moral argument against vivisection but who also ate meat by killing animals. Or, quoting proverbs, ‘Open thy mouth for the Dumb in the cause of all such are appointed to destruction’. A noble sentiment to protect and defend the oppressed whether referring to animals or the human being in its continuing waging of war and of the otherwise needless injuries, deaths, displacements, and misery of thousands. The Bible can be quoted again, (Ecclesiastes), ‘Behold, the tears of such as were oppressed and they had no comforter; and on the hand of oppressors there was power.’ Originally written as a moral sentiment regarding the collective human being, and which could have been written by the Karl Marx or the Frederick Engels equivalents of those far off biblical days, both of which men were meeting in a Manchester pub during the period that Dr Clay was practising, it was now being used to encompass all sentient, living beings and focussed on the rabbits, monkeys and dogs which appear to be the favourite objects of the experimenting surgeon. The Anti-vivisection League was created in 1875 and the Moral v Medical argument continued.

Spencer Wells claimed to have saved 500 lives at the expense of 14 rabbits but then again, mortality rates of the eminent doctor had been reduced by others while not exercising vivisection as a first port of experimentation it was also claimed. Charles Clay had achieved the same low mortality rate as Dr Wells without vivisection, having begun years before Dr Wells and Dr Wells being originally present at his surgery to observe his techniques in the early days. The two didn’t get on, sometimes quite vociferously, in correspondence. Charles Clay would claim that his oviarotomy had no more to do with vivisection ‘than the Pope of Rome’. The opposing argument being, ‘….Every advancement in knowledge of the human body has been received from vivisection.’ (Professor Humphrey of Cambridge as quoted in the Cambridge Chronicle and University Journal 1890). It was perhaps relevant for Charles to bring the Pope of Rome into the mix as there was a diplomatic interest in some areas to open negotiations with the Court of Rome during this period, and there was equal controversy over this suggestion.

The controversy of vivisection raged in the subsequent years with Dr Clay often quoted. It was a time when both Edward Jenner and Louis Pasteur were active in their own fields. Inoculation was a new concept and there were those who agreed and those who didn’t with their findings. Some only agreed with vivisection if inoculation or anaesthetic was used on animals for operating. Talking more about those who would rubbish inoculation as preventive of disease and champion vivisection alone, the knowledgeable correspondent of the Bristol mercury continues, ‘When it begins to dawn on the mind of the British public that all these diseases both for man and animals are absolutely preventable by the simple means of securing fresh air, pure water and abundant light, they will be banished.’ First things first, I guess as we are aware today. In the first instance, Dr Clay insisted on clean and hygienic surroundings and, further, a calm atmosphere in the operating room helped the patient.

Even in 1965 the opinion of Dr Clay is quoted in the cause of anti-vivisection in a letter to the Leicester Mercury, (an original quote from a letter he wrote to the Times, and also quoted in a newspaper article in 1908) ‘As a surgeon, I have performed a large number of operations, but I do not owe a single particle of my skill to vivisection. I challenge any member of my profession to prove that vivisection has in any way advanced the science of medicine, or tended to improve the treatment of disease.’ The same question was put by the Bolton anti-vivisection Society in 1906 quoting statistics of experiment, often without anaesthetics, conducted since the Animal Protection Act of 1895. Dr Wells would in opposition state that, of the lower animals, would you consider a rabid dog as more important than a human life?

But once a doctor, always a doctor and wherever you go as a doctor your skills might be needed. In 1843, as a member of the Manchester Philosophical and Literary Institution, he had attended the meeting in which George Wood, MP for Kendal collapsed, and Dr Charles was the respected doctor present. George Wood appeared lifeless. Dr Clay, on seeing to him, had opened the temporal artery after a pulse couldn’t be found and, since there was no consequent blood flow, the conclusion was that death had taken place and that there was no life within the body. It was a gentleman’s meeting and the subsequent inquest was attended by the same gentlemen to give evidence and who, regretting the loss of one their kind, concluded death was due to apoplexy.

In 1851, as a respected physician, he chaired a meeting in Manchester of the British Mutual Life Assurance Society acting, it seems, as medical advisor and described here as a referee in future claims. In this year too he is in receipt of bookseller, Willian Ardrey’s ‘real and personal estate and effects’ via an indenture and perhaps from here added to his large collection of books and numerous bibles.

In 1879, such was his evident regard, he acted as an intermediary in the conflict between medical personnel and the ruling committee of the Dewsbury Cottage Hospital and Dispensary when several members of staff tended in their resignations due to disagreement. His relationship with the members of the hospital persisted and, by 1891, he was presented with an ebony walking stick with an ivory handle and a silver mount by the Dewsbury branch of the St John’s Ambulance Association in recognition for the valuable instruction he had given them in previous lectures there. The walking stick was inscribed, ‘Presented to Mr Charles Clay, MRCS and LSA, by members of the St John’s Ambulance Association, Dewsbury District (male section) for his kind instruction in the above work, February 11th 1891’.

He also, as a member of the Manchester, and International Numismatic Societies had a valuable collection of coins and medals. His writings are extensive and much is housed at the Manchester library.

He appears to have had a quiet retirement in Blackpool, mving to the town psibly in the early 1880’s. His death occurred suddenly at his home at 75 Breck Rd Poulton (1891 census). He had returned from the short distance of a trip to Blackpool and had fallen lifeless out of his chair once seated. His death was widely reported in the press and he was three months short of his 92nd birthday. His quiet and private funeral was conducted in Poulton at 1.30pm and his interment at Layton cemetery Blackpool at 2.30pm.was an equally quiet affair.

On the death of his wife, Maria on the 25th August 1885 he had an address of 39 Queen Street, Blackpool. She was 84 years old. He was buried in the same grave plot as Maria.

Sources and Acknowledgements

Leading photo

Copyright Commons https://dcmny.org/do/2e6b8a95-ecc0-4769-831e-729c6b2fca06

Much of the information has been retrieved from The British Library Newspaper Archive accessed via Findmypast.

A description of Dr Spencer Wells’ experimentation and justification:-

https://europepmc.org/scanned?pageindex=1&articles=PMC2240904

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2405236/

Biog

Dr Lawson Tait on Dr Clay’s Death

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2405236/?page=1

Manchester Library archives;

Colin Reed June 21 2023

John Cristopher Derham

First Chief Constable of Blackpool from 1887 to 1911

The above picture would show a man who was 6½’ tall, with brown hair, a dark complexion, grey eyes and dark brown hair.

John Christopher Derham was born at 8 Dobb Lane, Failsworth, Manchester on October 17th 1846. The son of Catholic parents and a father of Irish birth who was also a serving police officer, he was educated at a Preston grammar school. He was originally intended for the priesthood but, in a change of tack on leaving school, he first took up a job as a cashier with a calico firm in Moor Lane Preston instead. This calico firm would continue to send material for his celebrated and much endeared and well-used Poor Children’s Clothing Fund in Blackpool right up to his death in 1911. After working here at the calico firm he then decided to follow his father into the police force and found a job at the House of Correction in Preston, first working as a clerk and storekeeper, starting on April 17th 1870. Meanwhile he lived with his parents, William and Catherine at the Church Hamlet police station in Broughton, his father now being a sergeant in Preston. He shared his home with his brothers William, Joseph, James and Alphonsus and a sister Alice.

It was at the House of Correction where he met Mary who was the matron there and they would marry in 1868. Mary would one day be known and well considered as the policeman’s friend with her association with Blackpool.

Soon after his role in Preston, he was sent to the Blackpool area on the Fylde Coast. Blackpool was a town still under the jurisdiction of the County as it had not yet received its incorporation and had no self rule. He was provided with the Marton District, just outside the town and itself not actually part of the growing and more populous township of Blackpool. He spent 18 months at Great Marton as a constable where he lived at Top o’the Town and where Arthur, the first child of the marriage to Mary was born. Mary’s younger sister Martha was also living at the address at that time. He continued in this role without incident and it came as a relief to him to be removed to Kirkham where he might see more action away from the quiet country lanes of this sleepy, rural district.

Dedication, resourcefulness, and the bloody-mindedness of pure altruism which marked his career was first manifested here in Kirkham where he spent three years in the office. His work was so satisfactory that he was promoted to sergeant. It was then, freed from the chains of pen and paper that the qualities now attributed to him came to fruition. The incident that earned him a promotion to sergeant was when he tracked a man, a wife murderer in Kirkham, all the way to Rochdale on foot, and captured and arrested him. It took him away from Kirkham for three days and two nights and his dedication brought him back to work and a promotion to sergeant in Preston. It was here that a new constable came upon the scene, a PC Brodie but there was no indication at the time that the two men would one day become to the two most important public figures in Blackpool when the same PC, then Alderman, Brodie was elected to the mayoralty of the town.

During his career on the beat he was ‘many times involved in hand to hand struggles with criminals of the roughest type’ and this included facing a gunman at point blank range, though there is a different, and more detailed account of this event on the Capital Punishment UK facebook site. While at Preston, John Derham reached the rank of Inspector after he had faced this gunman. The newspaper account states that he had heard shots from his office and immediately jumped up and out to investigate. He learnt that there was a man holed up in a room in the hotel where there was a small crowd around the front of it. The man inside, 24 year old Alfred Sowery, had just murdered his 19 year old girlfriend, a girl called Annie Kelly, by shooting her in the head and, perhaps in the guilt, fear or the fury or self-justification of what he had done, the man had threatened to shoot anyone who came into the room. But John Derham didn’t hesitate and burst into the room with his own strong self-justification of duty when the man called Sowery, true to his threat, aiming right at the policeman who had burst into the room in front of him, squeezed the trigger. John Derham would have been dead but the gun jammed as it clicked and Sowery attempted to jump out of the open window for escape. But the burly sergeant Derham grappled him and arrested him before he could use it. Sowery was eventually hanged and Sergeant Derham, a witness to the execution, made Inspector. The version on the facebook site, which appears to be accurate but no source given, is that when Sergeant Derham, (here referred to as Inspector Durham) arrived, Alfred Sowery held the gun to his own head and pulled the trigger, but the gun then failed. No doubt that in that instant, before or after the trigger had been squeezed, Sergeant Derham made the physical arrest.

Before that dramatic incident John Derham was involved in more mundane police work like staking out poachers. On the early evening of September of 1862 he had observed several men leaving the town in the direction of the open fields of Broughton and because they had a black sheepdog with them and looked somewhat suspicious, it was evident to him that they were intent on poaching, a regular offence of the day. With the help of two other police officers he kept them under observation and on their return at 4am confronted them and confiscated a bag of partridges off them, as well as beans and apples from the pocket of one of them which had been taken from the fields. The men were found guilty and fined, though one man, a Mr Maddock, pleaded that he had only 2¼d (2p; less than 5p in 2022) a day to feed a wife and family of three children. In his father’s heritage at least, Sergeant Derham would be aware of acute poverty and the starvation that inevitably and expectedly went alongside it. His conscience in his job, would have been challenged from time to time when circumstances such as these raised their heads.

Later in the January of 1863 he had no compunction in pursuing and arresting a man for the rape of a young woman whom the man had been seeing for some time. The man it seems had originally got off with the incident by offering to marry the girl even though it turned out he was already married. But aware of the injustice committed against the young woman, John Derham would not let the man remain free.

There is also reference to his brushes with industrial strikers and even Fenians both with their own justifications of challenging the law in conflict with John Derham’s strong held views of making sure the laws of the land are maintained.

In 1881 he is living as a police sergeant at No 3 Bolton St West in Preston, next door to the Fox and Goose and at No 5 lived police inspector Thomas Whitlam so the pub would have to be strict with it licensing hours. At this time John and Mary had five children and they were Arthur born in Great Marton, William in Kirkham and Mary, Herbert and Theresa in Preston.

The high regard that Inspector Derham was held in by all made him the only realistic candidate out of 60 applicants for the job at Blackpool after it had received its incorporation and he had the responsibility of organising its own police force. These 60 candidates were whittled down to seven candidates before interview for the job which was worth £200 (£20,270.01)per annum plus a house. These candidates in turn became two before JC Derham was appointed. In 1876 on the incorporation of Blackpool it was necessary to secure the correct sanction to create and maintain its own police force, divorcing itself from the County force. This had taken ten years and on June 1st 1887, Inspector John Derham arrived as Chief Constable with the task in hand of creating the local police force entirely from scratch. He would become respected by all who knew him (nearly all) and he was the right man for the difficult task in hand as the many tributes and good wishes to him throughout his life and in his obituary would testify. . He would be Chief Constable for the next twenty one years and nine months. During this time he established the increase in pay and houses for the married officers among the men under his command and, by the time of his death, the force numbered over 100 personnel. Recruitment was a continual process; ‘At the Blackpool Police Court on Saturday, Robert Cottam and Robert Rigby were sworn to serve as constables in the Borough Police force. On Wednesday, Joseph Kenyon was also sworn as constable.’ (Blackpool Herald Friday July 26th 1889.) In October 1891 he was awarded a salary increase from £200 to £250 (£20,072.01 to £25,090.00 )and then in 1896 to £400 (42,033.15) while the Lancs County Council provided £40 per annum for quarters and water rates (which ceased in 1906). By July 1901 his salary was increased from £400 (£37,896.10) a year to £500 (£47,370.12) with a guaranteed pension of £266 13s 4d (approx £25,200.91) when the Blackpool Watch committee extended his tenure for another seven years as he had no intention of retiring.

His first address in Blackpool is No 18 Alfred Street as shown on the electoral rolls. In 1901 he is living in Albert Road (not numbered but in sequence would be 131 and by 1911 at least, it is named Albert Lodge and which was next to the police station) with his wife Mary and six children.

In 1893 the high value in which John Derham was regarded within the force was demonstrated in a celebration given to him and his wife on the occasion of their silver wedding anniversary. It was held at the police station on Christmas day where they were presented with an electro-plated tea and coffee set on which was inscribed, ‘Presented to the Chief Constable and Mrs Derham by the wives and men of the Blackpool Police Force as a slight token of respect and esteem on the anniversary of their silver wedding, Saturday 16th December 1893.’ Both he and his wife were wished great longevity though Mary would live only until 1901. John Derham had been taken completely by surprise, he claimed, and didn’t know it was their silver wedding anniversary until reminded of it by his wife. In an awkward speech of thanks he was not aware that the meeting at the police station had been arranged for this event as the deputy magistrate’s clerk had arranged the meeting ostensibly for more civic matters. For an added detail, the tea service was provided by Mr Pecket of Bank Hey Street.

His wife Mary died on the 8th October 1901 when a long illness and time in a Manchester hospital before coming home only to catch pneumonia couldn’t prevent the natural, if regretted, event from happening. She was buried in Layton Cemetery and her funeral was attended by a large number of mourners. As many policeman as could be spared duty were in attendance and eight sergeants carried the coffin with about thirty other officers in her cortege. Later on in 1905 he had to deal with the suicide of his eldest daughter who was working as a nurse in Bootle Corporation Infectious hospital. She was 27 years old and was well liked. Tragedy stalks success and is sometimes even encouraged by it.

In the varied work of the police service Inspector Derham had to deal crimes and incident of various natures.

In 1902 two runaway boys from Preston, aged ten and twelve, one of them, ten year old Samuel Walker, was a veteran of running away from home to escape, he claimed, from his brothers who kept hitting him. Whatever the reasons, he found that sleeping rough in Blackpool was better than any other option he might have had. It wasn’t the first time that the police had had to deal with him and he had been sent him back to Preston on the train and they were now at a loss as to what to do with him since he would keep returning. He was, after appearing in the court put in the care of the Relieving Officer, since there was nothing else that could be done.

Another mundane duty of the police force was to keep a check on gambling but an attempted prosecution of John Wood, the licensee of the No 3 and another man for taking bets on a bowling game at the premises was thrown out as the officers assigned to the incident had naively compiled their reports in identical language some time later at the station and so left themselves open to accusations of constructing evidence for their own convenience. The gambling laws were subject to a specific language leaving a lot of space for interpretation and convictions could be wriggled out of.

Regarding the application of licenses for alcohol the police sometimes had a hard job to convince the magistrates, but drunkenness and the reasonable consumption of alcohol was a matter for both and if Inspector Derham thought that a licence should not be granted at a certain premises, he would need to attend the Licensing sessions and put forward his case. There was a case where a licensed premises was under scrutiny and Inspector Derham wanted the licence removed. The house wasn’t identified but it was one of Messrs Brown & Co and had been operating for over 30 years in a densely occupied area of Blackpool and the licensee at the time was a Mr Milner who had since left. The solicitor for the defence was out to win his case for the brewery company and Inspector Derham had his work cut out to maintain his claim. Inspector Derham’s claim was that there was always trouble, and occasional violence at this house and that the landlord had touted for customers by advertising the presence of a bearded lady and a giant within the premises and these features were encouraged by touts at the door. But once inside they could only be viewed by the purchase of alcohol. With banter backwards and forwards across the benches, the licence was eventually granted but only because a new landlord had been found for the premises and the promises of good behaviour had been ascertained. Drunkenness was a continuing problem not helped by the ‘back door’ of many a premises whereby customers could enter after hours and there was little the police could do about what is a natural attraction to alcohol in any community. Inspector Derham’s efforts and those of the police were however respected as it was their duty to monitor those aspects of the community that might adversely affect the good running of society in general. There was also the issue of theft in all its definitions sometimes brought on through sheer self interest and personal gain like the jewellery theft from a shop in 1910 and other times due to circumstances which make the crime worth the risk of being caught when there was no alternative but to starve or sleep out in the cold like the two well dressed young ladies who picked the pockets of unwary market shoppers in 1906. The police had to prosecute and the magistrate had to decide on the correct manner of punishment given the circumstances.

And in 1903 he and his officers raided No 19 Ashburton Road and arrested the owners for keeping a disorderly house in line with the requirements of the Blackpool Improvement Act. And another mundane task in 1908 was to arrest a man found selling crowing cocks and which had been making an awful noise. But in this case the court couldn’t prosecute without some understanding of the noise so the Chief Constable who was present was asked to demonstrate the noise. With a sense of Irish humour or an attempt to reproduce the generally good singing voices of his father’s countrymen, got up to ‘sing’ like a crowing cock. Perhaps it was successful for the accused was fined 10s (50p; £46.36) amidst the laughter and to the general amusement of the court.

In 1900 he had been served with a writ for accusing Ellen Nickson, a stall holder at the market, of being a drunken woman of loose character. He had been served with the writ by a man who had called at his house and who threw the writ at him as he met him at the door which had been answered and opened by one of his children. He didn’t know who the man was who was laughing and sneering at him but soon learnt that he was the husband of the woman accused. Taking exception at this he threw the man out bodily but injured the man’s head in doing so. It’s difficult to know just how he felt at the time, whether he had a sense of occasion or he was out to save his own skin, but the injury caused some remorse and he offered the man compensation £5 (£473.70) changed to £150 (£14,211.04), as mentioned in court later. If there was anyone out to get the Chief Constable they were disappointed as the case was, quite correctly it would seem, found in favour of John Derham. He had been in court as early as 1888 when one of his constables had resigned for undisclosed reasons. He was claiming compensation for wages lost under an assumed arrangement on his employment by the Chief Constable the previous year. The wages for a police constable at the time are stated as £1 5s 2d (c £1.26) a week and 10s (50p) had been stopped from his wage because he hadn’t completed the required probationary period. It was this 10s that PC William Collier was claiming had been unfairly deducted. The case found in the Chief Constable’s favour.

John Christopher Derham was for 25 years associated with the St John’s Ambulance and he became the Senior Assistant Commissioner of the district and a senior figure in the national organisation. He nurtured the women’s division of the St John’s Ambulance and the women, under the head of their Ladies Nursing Division, Mrs V M Orme, were also active in the distribution of clothing for the poor children of the town, a charity begun and continued annually by the Chief Constable. One of the newer recruits in the Ambulance Division would go to France during WW1. He was Stanley Boughey and would eventually receive the Victoria Cross. Another police Inspector, Alfred Victor Smith, who would also receive the same highest reward and both are commemorated on the Blackpool cenotaph. In 1906 while presiding at the Argenta (a commercial meat company) Ambulance Cup held in Blackpool at the police station for the St John’s Ambulance, (in which Blackpool 4th Division came 2nd) for three divisional districts and in which 10 teams competed, the Chief Superintendent was awarded with a long service medal. On receiving the medal he was described as, ‘one of the heartiest, most sincere, and most enthusiastic ambulance workers who had ever been decorated.’ John Derham had the distinction of being a senior serving brother of the Order of St John of Jerusalem and his medals were numerous. He had received an ambulance medal from King Edward VII which he received from George V (as Prince of Wales). He possessed the long service medal of the brigade and the jubilee medal of Queen Victoria which he received for organising a force of 800 men to guard the streets of London during the Royal Jubilee Procession. This latter would have been in 1887 which would have been a very busy and significant year for him.

In 1903 he circulated the portrait of missing woman Alice Webster whose disappearance had caused quite a sensation. Missing from Blackpool, some of her personal items were found on the cliffs at Bispham which was not part of Blackpool at the time. She did eventually turn up in the Midlands her home district, living incognito. This story is related on another page.

The Clothing Fund

The Lancashire Daily Post of January 2nd 1907 begins its column on the police clothing fund in Blackpool with, ‘A Blackpool of bracing breezes or varied pleasures and inexpensive amusements, we know, but is there really a Blackpool containing ragged and starving children?’ Indeed the paper goes on to expand that when the summer visitors have gone there is still a population of workers resident in the town and those with low wages or who have not been able to stash a nest egg for the winter will suffer from hunger and the cold.

With this in the forefront of his mind no doubt and having experience of Blackpool already, the clothing fund was started in 1890 and which was to earn him the sobriquet of the ‘Fairy Godfather’ among all the children of the town. The alternative to a charitable consideration for these people was destitution or the Poor Law. Without any kind of promotional assistance at first, nevertheless 184 children were provided with clothing. By 1903 over 1,000 children had been given clothing and due to the success a committee was formed to administer the fund. A sports fund was held at that time to raise means but in the following year the Tower Company defrayed its costs and donated its profits for a matinee held at the Palace Theatre of Varieties and this became an annual event. In 1907 it raised £340 (£31,526.33) and 1700 children benefitted with the numbers ever increasing annually. Most of the clothing was new and much of this was made by the Blackpool Ladies Ambulance Class under the auspices of Mrs V Orme. Some of this work was done at home but there was a room set aside at the police station for the purpose and the work continued all year round except for a short, summer break. Shoes were generally provided by local tradesmen. Annually this amount of clothing reached 10,000 articles which included 1,000 suits, 1,164 pairs of stockings, 1,142 pairs of clogs, 1,270 of shoes and boots, 1,551 pairs of socks, 532 bonnets, 330 overcoats, 460 shirts, 638 caps, 800 dresses 1,140 petticoats, 386 jackets, 360 singlets, 95 pairs of trousers and knickers and 74 jackets and vests.

Subject to fraud when the clothing could be pawned by an unscrupulous parent, this clothing was provided with an identity mark. On different occasions, as the children arrived at the police station to receive their items they were given a hot cup of oxo and a slice of bread on receipt of the clothes and on other occasions were given an orange and a toy. The ambulance ladies saw to the girls and the policemen to the boys. The line of children waiting to be fitted out presented a sorry sight and occasionally a parent could be seen weeping to see their child in good clothes for the fist time in its life. While the distribution of clothing was usually conducted in January, the work however went on all year round and, when those attending school were found to have insufficient clothing or couldn’t attend because there were no shoes to wear, a head teacher would contact the police for their support, and it was given. Some contributors to the fund wanted their money to be spent in a special way and thus the police became the middle men in providing such things as groceries or coal.

In the beginning he had at first organised an annual Christmas tea party for the children but this had got somehow got out of hand due to the large numbers and so it had to be abandoned and he then opted for the distribution of the clothing instead. For this purpose the matinee was held at the Palace every autumn and the one held in 1910 achieved an amount of over £700, (£63,554.92) and the matinee Committee had, during 1911, raised £1,420 (£128,925.69). Inspector Derham’s philanthropic work was dominated by this Poor Children’s Clothing Fund, but it appears that the children’s parties had been reinstated as in 1905 an article in the Leeds Mercury of 26th December 1905 reads, in the sentiment of the day, with a heading, ‘Blackpool “Bobbies” as Seasonable Friends’; ‘The police appeared in the charming role at Blackpool, yesterday, when charity was anything but cursed by the unemployed. Some two hundred families received, as a result of contributions from better class residents, parcels of provisions value half a crown (2s 6d; 25p; £93.72) each, while in the afternoon between five and six thousand children sat down to tea in the Assembly Rooms, Talbot Road. The constables co-operated with their wives as waiters, and afterwards added to their reputation as entertainers on the boards.’

In 1908 the Chief Constable’s Poor Children’s Clothing Fund had reached over £566 (£52,482.06) and on the Saturday 9th January of the following year 2,200 children were received at the police station and ‘clothed from head to foot’ with new clothing and serviceable footwear.

My grandfather used this facility later on in the later 1920’s when clothes were provided at the police stations in this case at Marton. He would dress my mother in ragged clothes and exchange them at the police station then redress her in the poor clothes and sell the new ones in the ‘Rag’ across the road. A gambler too he would gamble away the furniture until he was obliged to leave home for good by a wife who had had enough. His character had reportedly changed from good to bad due to WW1 service. At this time the fund had been taken over and continued by Inspector Herbert Derham, John’s son.

By the time he had reached his 60th birthday, though he had qualified for a handsome pension, he declined to retire but continued in his job, eventually dying with his boots on as it were. His 60th birthday in 1906 was held at the Park Hotel (which by 1911 had changed its name to the Carlton) and it was attended by all the civic dignitaries and he was given a silver platter and a cheque for £500 (£46,860.77). He hadn’t liked to cash the cheque and by his death five years later, it still hung in a frame in his office.

Just before the Chief Inspector’s death, when evidently not well and his son and friends entreated him not to go to London to collect clothes for the fund, he stubbornly had his idea and he kept to it. The matinee for the fund had taken place the previous day when 4,000 had attended and, secured with the funding from this he had set off for the capital. He had returned three days later when he expected to take part in the mayoral procession on the following day, the Sunday.

His death occurred just after he had returned from London after buying a stock of clothing for the New Year’s distribution of clothing for the poor children. Having arrived home at 5pm, he felt unwell and went to bed. The doctor was eventually called to his house which was next to the police station on Albert Road and he continued to rest, his condition improving then deteriorating, and he had his sister, Annie, ‘congenial and much admired right hand helper’ to the landlord, Mr John Barnes of the Sergison Arms in Haywards Heath to nurse him. He eventually died on the Wednesday evening November 16th 1911 and the news of the popular man quickly spread around the town. The following day the Town Hall flag flew at half mast. He had been a singularly minded person who had had a clear idea of right and wrong. As the Fleetwood Chronicle writes, ‘…few anticipated the blow that fell on Wednesday night, when we were robbed of the genial, beloved figure of our Chief Constable Mr John Christopher Derham….We have lost in him a most able public servant, the poor have lost a friend who was a friend indeed, very many of our best known citizens have lost a companion who was beloved by all who enjoyed his friendship.’

Known in the force as the ‘policeman’s friend’ in Blackpool, he left a grown up family. W T Derham his eldest son was in the Manchester City police force, Herbert (who would become Chief Constable of Blackpool in 1919) was superintendent in that force and Charles was in the County force. Another son broke the trend and was an architect in London. A married daughter, Mrs T Donnelly lived in Poulton.

He had been 41 years in the police force, a career which from the humblest of beginings rose to the highest ranks through the ‘gallantry, bravery and marked resourcefulness’ of a remarkable man. ‘He leaves a police force which is second to none in the matterof organisation and efficiency, and in the hearts of the men who were under him he leaves memories of a kind and beloved Head.’ (Fleetwood Chronicle 17/11/1911). The force for which he had secured increases of pay and houses for married men in his good relationship with the town’s Watch Committee, now numbered 100 men of all ranks.

Tributes; William Read led the tribute to the recently deceased Chief Constable at the meeting at the Blackpool Liberal Club and at the Congregationalist Church on Victoria Street a similar reference of sympathy and condolences for the family was issued.

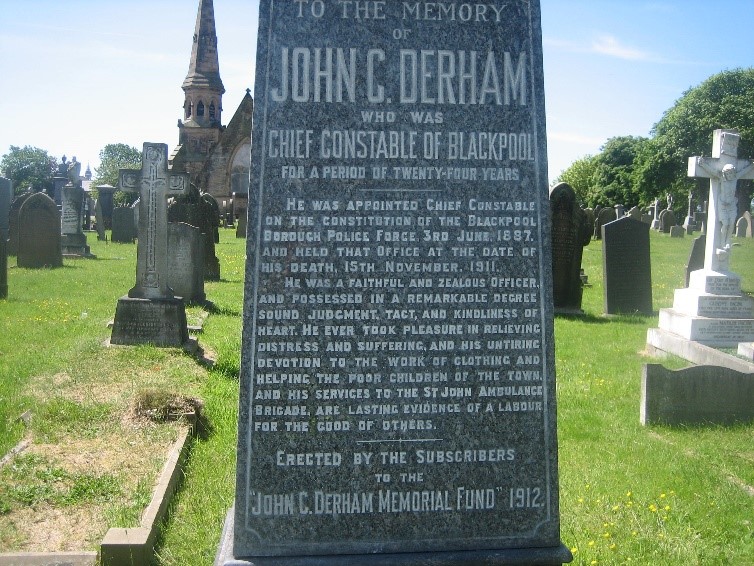

‘The body was received into the church of Sacred Heart on the evening before the Requiem Mass of 21st November. On the following day after the service, his funeral cortege wound its way slowly down Talbot Road to Layton Cemetery where his monument stands today. An extract from the Blackpool Gazette News November 21st 1911 and kindly provided by Philip Walsh reads, ‘The townspeople of Blackpool did worthy honour to their departed Chief Constable on Saturday. Thousands of people assembled in Talbot Square and along the route to the Blackpool Cemetery, by just turned noon, to pay their tribute to the late ‘Chief’ Mr John Christopher Derham, and a more impressive funeral has not been seen in Blackpool for the past 15 or 20 years. Every section of the community, practically, was represented in the great procession which must have been considerably over a half mile in length. As well as local dignitaries many local associations and trade organisations were represented in the procession from Talbot Square to the Cemetery.

He left four sons and three daughters each at the service along with other family members, in -laws and grandchildren. His son, Mr William Tate Derham would be in charge of the funeral arrangements.

John Christopher Derham is buried in Layton Cemetery which has plenty of characters within its resting grounds and many stories tell of Blackpool and beyond in many areas of life.

His death was attributed to acute cholecystitis and hepatitis.

The memorial fund of £500 (£45,396.37) was spent on the endowment of a cot at Victoria Hospital and the remainder of £194 17s 11d (£17,613.79) to be spent on a monument to be erected above his grave and a portrait to be placed in the Art Gallery. Probate shows he left effects of £2784 10s 4d (approx £252,766.98).

The clothing fund was taken on and continued by his son Herbert who was also in the Blackpool police force and would one day too become Chief Inspector by 1919.The annual matinee at the Tower however, was discontinued in 1930 by his son the then Chief Constable over allegations that he had compelled members of the police force to sell tickets for the event. These allegations, which appeared to have circulated secretly were vehemently denied and he claimed that he would give £100 (£5,038.21) to the Victoria Hospital if anyone could prove them.

No-one did, or could.

Sources and Acknowledgements. The story has been largely extracted from the British Newspaper Archive via findmypast. Thanks to Denys Barber for the picture of the gravestone and to Philip Walsh for the newspaper extract and personal details of John Derham from the police records at Lancs County records offices.

John and Angus Cameron

Brothers John and Angus Cameron were Bispham residents from the creation of the Blackpool and Fleetwood Tramway in which they were intimately involved, until their deaths in 1921 and 1935 respectively. Both are buried at Bispham Parish Church. Angus the chief electrical and mechanical engineer and John the manager of the Tramway. Both arrived at the beginnings of the tramway, Angus in 1897 and John a little later in 1898. The Tramway went as far as the boundary with Blackpool at the Gynn from where the Blackpool Corporation Tramway had been functioning since 1885. The two Tramways were not joined until the Blackpool Corporation had bought out its neighbour in 1920.

Electricity was the next best thing at the end of the nineteenth century, soon beginning to replace gas as a source of light and domestic power. For the tramways, electricity had to be produced in larger quantities and at first, before overhead cables the power came from the trackway in a channel in the centre of the lines. This of course could constitute an obstacle to the unwary tripper and a fascination or curiosity to which would give the unwary a shock. The Blackpool Herald of 1889 explains with a little sarcasm, ‘Several persons have received shocks to their system, for which they would have to pay at any of the well-known places in town.’ This kind of shock however, was entirely free but of such a nature they would not want a repeat. . Two young boys received the same shock gratis as well as a spade placed in the tramway groove and which had consequently become reduced in size, and another who had a similar experience with a set of keys. The advent of the overhead power system in the near future would have been welcomed by many.

Angus Cameron

Angus was the chief mechanical and electrical engineer of the Tramway and had, with working experience in iron and steel manufacture in Scotland, been an agent for the Laxey-Snaefell railway on the Isle of Man. Angus as chief mechanical and electrical engineer of the Tramway Company had arrived in 1897 and was responsible for laying down the first piece of track and supervising the rest. He had lived, before his ill health, at Old Red Bank on Hesketh Ave (which on the electoral rolls of 1920 includes the numbers 10-14) during his working years. His next door neighbour at one time was TG Lumb, one time Bispham Urban Councillor like Angus’s brother John, and Council leader at one time, like Angus’ brother too. Angus is described as a quiet, retiring man though well liked and with many friends and his association with the Tramway had waned from the public mindset by the time of his death so there is less known about him than his more outgoing brother John. Angus however presided over the annual suppers in connection with the Blackpool and Fleetwood Tramway Company Employers’ Sick Benefit Club which took place at the tram terminus waiting room in Fleetwood. Each year there were toasts to the future of the Company and always had one careful eye on the swiftly developing neighbouring town of Blackpool. In 1911 at this annual get together they were assured of the competence and good business mind of the manager John Cameron under the aegis of whom, the Company had produced a dividend of 9% and which produced much rightful self-congratulation among the shareholders present. Aspirations for the future were equally as high for the Company as they were patriotically for those of the country itself in which the military had been praised for the laying down of life and the spilling of blood in conflict for its sake and it was hoped that should such a circumstance arise once more that their countrymen would be as willing to join the conflict as those of the past had done. It was a kind of a chilling prediction, since Angus was to lose a son in the World War that was inevitability but unwittingly approaching in its ferocity. But on a more positive note, concerning the sickness contribution fund provided by the company for its employees it was hoped that a system of national Insurance could be introduced by the Government as much as had been done recently with old age pensions.

Angus, died at his daughter’s house, Sykes Head, 116 Cavendish Road in 1935 aged 80, seemingly after a heart attack. He had been in failing health for some time previously.

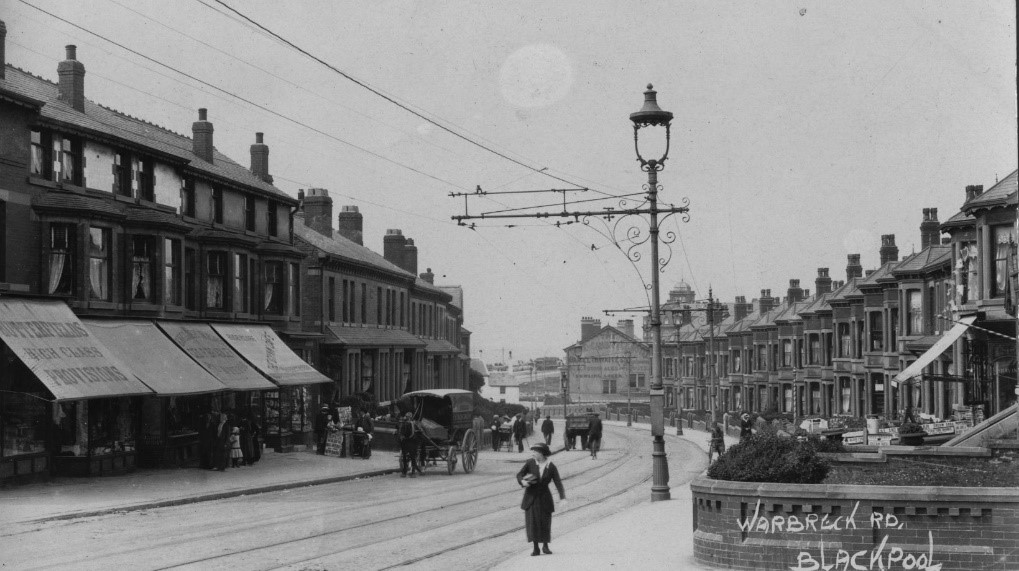

Angus’s son, also Angus trained and became an electrical engineer on the Tramway, living on Daventry Ave with his wife Ethel and eventually on Warbreck Road where he died in 1962.

As a generation that had provided soldiers for the Great War, Angus and his wife Maria lost their son, John Gordon Cameron who was killed at Cambrai while part of a Lewis gun team.

He was 24 years old and had been an assistant teacher at Baines Grammar school, Poulton before joining up. He was an active worker in connection with the Bispham Church and was intended for the Church expecting to study for Holy Orders when he returned from the Front. In a letter to his parents Lieutenant W Young, states, ‘The officer commanding was wounded, and I was left in charge. There were only 40 of us left in a post at which the enemy launched a very heavy attack. We held the position for twenty four hours and during that time your son did very valuable work. With the Lewis gun team, he and two others, who were all that were left, held on to their position to the last. He was shot through the lung, and his death was almost instantaneous. We shall miss him very much. He was not only a skilful soldier, but in all trying conditions he was always cheerful. You have my most sincere sympathy, and that of his chums, in your sad bereavement.’ He was sadly missed in the Bispham community too and his parents expressed their acknowledgement of the sympathy received by all with a brief inclusion the newspaper.

The War of course brought women into a focus that they had been demanding for some time and the trams saw women conductresses for the first time. At the time of John’s death his mother would have received the vote for the first time along with others of her age group.

John Cameron

John arrived in 1898 as appointed manager of the Blackpool and Fleetwood Tramway. As Scotsmen, he and his brother had not only brought a flavour of Scotland to Bispham with them but also a Manx flavour where both had worked on the railways there before coming to Bispham. Reading the census returns of the relevant time period, there were several people employed on the trams with addresses on Red Bank Road. Up and down the road there is many a tram worker in residence, either as inspector, conductor or cleaner and some of these had originated from the Isle of Man. The household of John Cameron had also brought their domestic help from the Island. At least one of John’s children, were found work on the tramway. His daughter Cissie at 17 years old was a clerk on the Tramway in 1911, so there was much of a family connection in the Company.

John Cameron, like his brother was there from its beginnings to its transfer to Blackpool Council on January 1st 1920, He died at 68 years old on 5th March 1921. His death was sudden and only a week previously had been over to Yorkshire to see one of his daughters and had shown no signs of illness then. It appears that he had always been a generous minded person and he had always hoped he would die quickly-but only so he wouldn’t be a burden on anyone else.

There is more known about John Cameron than his brother Angus since there is more written about him and probably because he died when he was still in the news and his name still on the lips of many. His death in 1921 was shortly after the Blackpool and Fleetwood Tramway had been taken over by the Blackpool Corporation tramway and the Gynn terminus of both could be scrapped and instead the two lines could be joined to create a continuous, coastal line. More specific information comes thanks to Nick Moore’s comprehensive work on Blackpool’s history where he states that in 1919, the tramway was bought by Lindsay Parkinson, and sold on without profit to the Blackpool Corporation without profit. Lindsay Parkinson as ex mayor which office he held for two of the war years, was energetic in the annexation of Bispham, in which the Gynn was situated, into the corporation of Blackpool.

John Cameron had been a strong willed, hard-working, and straight talking man. He was also a close family man, and he had numerous children with his first and second wives. His first wife Margaret had died in 1891 in the Isle of Man aged only 40. In Bispham as reported in a lengthy newspaper obituary, he enjoyed the fireside evenings with Elisabeth (‘Lissie,’ whom he’d married in 1893 in the Isle of Man), and children as no doubt he had done with his first wife Margaret both in Scotland and the Isle of Man. In the 23 years that he had daily travelled the tram route that he had built and now managed, he had become a popular figure among everyone with his ever cheery disposition. He was a generous man and his wealth was always at the disposal of anyone that came knocking at his door with a genuine need. He was a popular, well liked man, a member of the Bispham Urban Council, a Freemason and a prominent member of the Bispham Lawn Tennis and Bowling Club. He also had an interest in the Fylde Motor Service which served the Over Wyre district which would have been a natural a continuation of the tram road over the river estuary via the ferry. His passing was regretted by many and his funeral was a shop closing, blind drawing, street-and-church-packing event.

His first residence in Bispham, a little village attractively described as ‘Bispham by the Sea’, at the time was at 211 Warbrick Road a short distance to his offices at Bispham, though Warbrick Road (now Warbreck Drive’) didn’t extend all the way from the Gynn to Bispham at the time, so he would probably have taken the tram, boarding it at Uncle Tom’s if inclement weather prevented him from making the journey on foot. But he eventually moved to the house by, or on the premises of the Tram Depot and Electricity Works and fronting Red Bank Road which he called ‘Pooldhooie’, ‘two minutes’ walk from the tramstop.’ It was the name of his former residence in Ramsey, Isle of Man where he was living and working as secretary of the Manx Northern Railway, a part of which he had been involved in building, immediately before accepting the appointment at Bispham to manage the construction of the Tramway. When he came to take up the post in Bispham he had tapped into the workforce he knew well on the Island and who had worked on the railroad with him. The house itself is now the sole survivor of the defunct electric tram depot and while Sainsbury’s has risen in the place of the works and the sheds, the house survives as the Conservative Club though has evidently seen some modification in its time since. The house was sold in 1925 by his wife Elisabeth and described as a ‘valuable detached freehold villa’ with vacant possession so the family had no longer a connection with it after that.

At the time, he lived in a Bispham with more open spaces than today. Consulting the 1911 census returns, and the OS map of 1909, Red Bank Road is a collection of a few houses and farms with open space in between. Eastwards, his nearest neighbours on that side of the road were the Cartmells of Sunny Bank Farm. Directly after Sunny Bank Farm and across the road there is Uptown Farm also occupied by the Cartmells as was Knowle Farm a mile or so further away and up the Knowle hill. Bamber’s Farm is situated next to Uptown Farm. Towards the sea and after John Cameron’s, large, detached house (‘with double fronted bays on both floors’) is Cliff Terrace and the collection of houses that are Hesketh Place and Avenue. His daughters appeared to be lively lot and a supper and ball held by his three eldest Jessie, Cissie and Chattie who were older teenagers and all born in the Isle of Man warranted an inclusion in the newspaper as they held the party for friends at the Norbreck Hydro.

From the cliffs there at the top of Red Bank Road, as he stood by the Bispham tram station, the family might on occasion have been able to see the twin peaks of his former island home in the distance across the sea. I’ve certainly seen them myself from the shore there on a single occasion, along with a brother and sister as we had just left the Highland Hotel at the corner of Hesketh Avenue, after a pint. It was definitely the natural phenomenon of the light rather than the strength of a small intake of beer. There is no record of any of the Cameron’s returning to the Isle of Man but, if they did and probably would have done, they would have travelled across to Ramsey from Fleetwood at 2.15pm on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday or Saturday and the return journey from Ramsey on the same days, though Friday rather than Saturday.

While in the Isle of Man John had been secretary of the Manx Northern Railway and had been on the island since 1878 where he had undertaken work first as a subcontractor before becoming a railways inspector and then fully in charge. When he left he was given a good send off with plenty of gifts and felicitations. He was well liked and in the minds of many he was an honorary Manxman. He had come over to the Island with his wife but she had died in 1891 and he married his second wife Elisabeth, daughter of a master mariner Thomas Callow who was also a successful businessman and member of the Oddfellows. Thomas is reportedly a generous man and in nature not unlike John Cameron himself so there was a natural connection there and his daughter Elisabeth would probably have been well known to John already in the society that he kept. John eventually bought Pooldhooie, in the Lazyre district of Ramsay, as the family home. He had bought the house off the executors of the estate of an eccentric and reclusive old lady, a Mrs Mercer who had died in strange circumstances, sat upright in a chair behind a bolted door, a door which had to be broken open to gain access. There was a controversy over her will at first but this was legitimately resolved with her estate being left to the rightful beneficiaries. But John Cameron wouldn’t have been spooked by any of this since he was a practical person and would show contempt for anything insubstantial and he lived there for a short time with his second wife until his move to Bispham. One of his hobbies on the island was an interest in dog breeding winning many prizes in the annual shows.

Before moving to the Isle of Man he had been a successful railway subcontractor and he had worked not only in Scotland but also on the Settle-Carlisle line. Engineering was in his blood and he took every opportunity to visit any engineering work that was under construction near at hand, whether it be a railway, a reservoir a bridge or indeed anything. While he was in his job as Tramway manager at Bispham he had been approached by the Edinburgh Corporation to sort out the tramways in the city but he had evidently declined the offer, preferring ‘Bispham by the Sea’ to the illustrious capital of his homeland. He was a clever and astute man and also physically adept and by the age of 19 he was a ganger in charge of 120 men on the Settle/Carlisle railway and earning £3.15s (£3.75; very approximately £400 today) a week. He possessed physical qualities which were equal to the rough nature of the job (he had charge of the part of the line just above Langcliffe) and, always ready for a scrap if need be, he was able to ‘take care of himself’ as men who believe they possess confidence in their physicality might brag and he had on one occasion put a man, probably an older man since John was only of a young age at the time, on the floor with a heavy blow after he had been subjected to too many taunts about his favourite breakfast of porridge.

He had a positive attitude to life and was straight talker not liking hypocrisy and if any controversy arose with the men of who he was in charge on the tramway they would be faced in the office with, ‘Let’s have the whole truth and nothing but the truth to start with, and then you can tell as many lies as your conscience will let you by way of excuse.’ He ‘liked straight men’ which would be interpreted differently today in the evolution of language but meaning that he liked those (and which would include women too no doubt) who would hold honest opinions and be able to argue them objectively. He was up and about earlier than most and was promptly at his desk in his office of the Bispham Tramway Depot by 9am busily working.

John was a wealthy man though not entirely selfish with his material comforts. He was a Freemason and a member of the Ramsey Lodge. He had become a member of the Foresters in 1886 and by 1897, in what would have been his last annual reunion on the Island, he was the chairman. It was a grand occasion, all members being in full regalia, several arriving on horseback and the highlight of the show being a stage production of Robin Hood. In his address he praised the success of the Foresters which as a society might be considered a kind of admix of socialism and capitalism. Look after yourself and your own but perhaps you would need some kind of conscience to truly belong in order that some wealth that could be considered superfluous and could be distributed to those in need. The Forester’s assets were backed by the acquisition of real estate and John Cameron himself sold off a second property he had in Ramsey with a sitting tenant before he left the island in 1898.

In Bispham he found time to serve on Bispham Urban Council and was leader in 1906 and 1907 having served on the Urban Council since its inception in 1900. In an electoral address in 1914 he appealed to the voters stressing that as he had seen the improvements of the roads northwards to Fleetwood, he would insist on the same improvements to those roads within the Gynn Estate (both Uncle Tom’s and Fanny Hall had been part of the Gynn Estate and the new Uncle Tom’s still was.) He also stressed the need for the Urban Council to take over the shore rights as these were in the hands of private individuals (much as Blackpool had been its early days) since the cliffs needed securing to forestall the continuing erosion. The Council had previously wrongly been blamed for not doing anything about the erosion. His electoral address was printed in the paper along with those of James Handy of Ivy Cottage, Robert Brown of Bamber’s Farm, Fred Thornton of the Red Lion, TG Lumb now of Stockdove Wood in Cleveleys and James Hague of Brentwood, Bispham Place. All the candidates had a largely similar agenda.

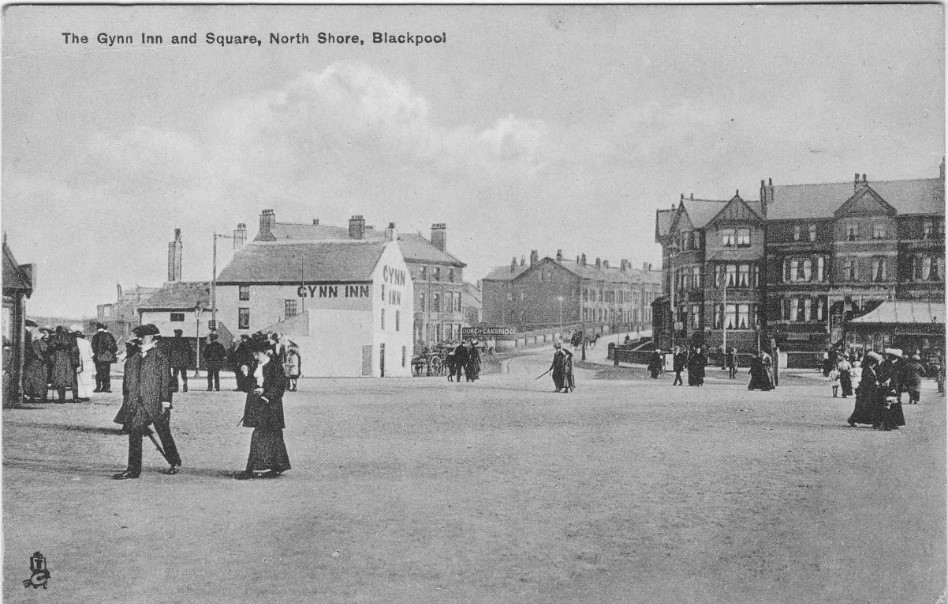

By 1920 he had sold the going concern to the Blackpool Corporation for around £300,000. Its lease had run out by then and Blackpool was keen to expand northwards, annexing Bispham at the time also. John, as an astute business man, received £10,000 in severance pay for loss of occupation. At that time the Blackpool and Fleetwood tramway had a terminus at the Gynn, its southernmost point and where the Blackpool Corporation tramway, first conceived in 1884, also had its terminus at its northernmost point here, and you had to get off one and board another tramcar in order to continue the coastal journey. Once the Blackpool Corporation had bought the line and the rolling stock too, the two lines were connected along with the redevelopment of the Gynn, which included the demolition of the old Gynn Hotel and the creation of Gynn Square. But this was after the time of John Cameron.

At his death, his youngest child was his son who was 14 years old and was one of two boys at Kirkham Grammar School. His youngest daughter was at Blackpool Secondary School. His son John was the manager of the Northampton tramways (but who could not attend the funeral because he had broken his leg) John’s son Angus survived the war and died in 1962 while resident at 298 Warbreck Drive. A couple of his children had emigrated. John’s son David joined the Canadian Foresters during the War and was in charge of the mechanical department. He had died only in the previous September of 1920 in Canada.

Information from several newspapers from the British Library museum.

http://myday.si/index.php?c=events&view=detail&id=920&d=29&m=9&y=2021&cm=10&cy=2021

https://blackpoolheritage.com/tours/history-of-our-tramway/https://lilaoliver.wordpress.com/2009/10/31/bispham-depot-and-situated-down-red-bank-road-was/

Alice Ashworth

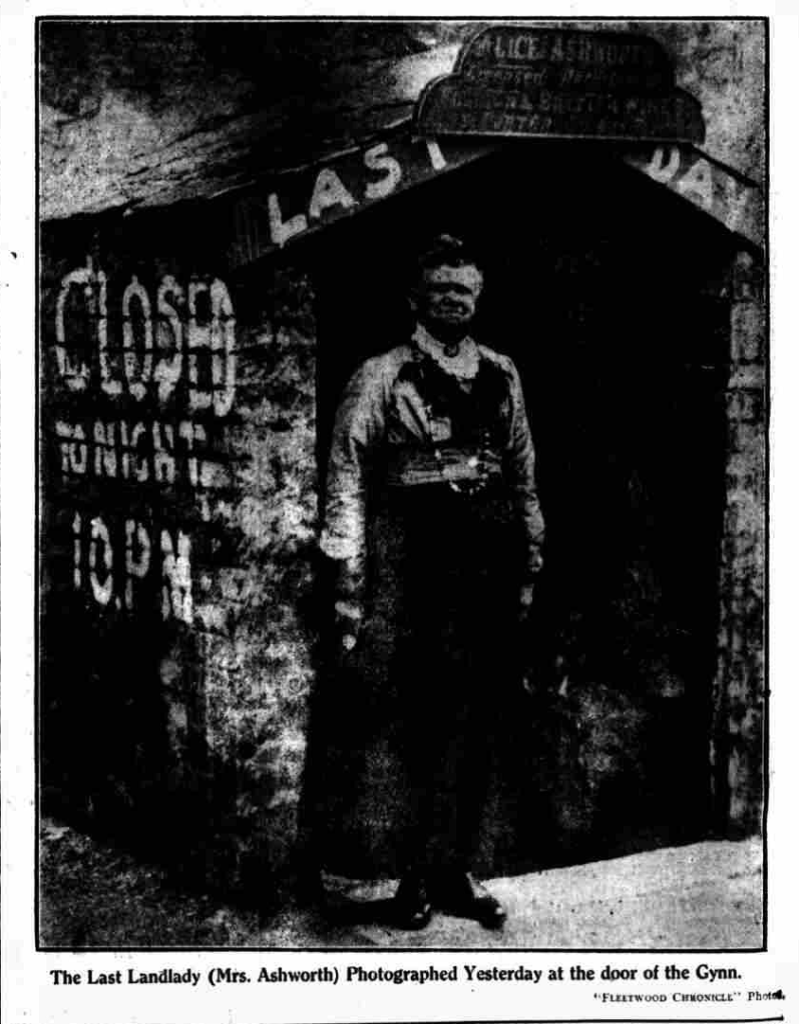

Last Landlady of the Old Gynn

Shown at the door of the Inn on its last day, and pictures from the newspapers do not always digitise well, it is not a very flattering photo of Alice Ashworth, but I’m sure in her Sunday best and a pleasant, engaging smile which can create a beauty in even the plainest or oldest of faces, she would have been able to capture the hearts of many.

Alice Ashworth was the last licencee of the old, whitewashed Gynn Hotel before its demolition in the early 1920’s. In her pre-married name of Crossley, she originated from Stacksteads near Bacup, a village deeper into Lancashire from the seaside at Blackpool. Stacksteads is a little east of Waterfoot from where her husband, James Ashworth, originated. Cotton and woollen mills occupy the valley which, at a glance at the census returns, employed many of her neighbours, friends and a family. This valley beneath the moors within the Rossendale Forest and recently occupied by the East Lancashire railway line, would be her earlier memories before moving to Blackpool sometime before 1891 when she would have been in her thirties. The census of this year of 1891 doesn’t show Alice in Blackpool at the Gynn Beerhouse with her husband James and two of her sons, George Edward Ashworth 19, and Edward Lord Ashworth 13.

She is found instead, at her sister’s, Elisabeth Nuttall, back in Rossendale with a son and daughter, Oliver and Mary, Elisabeth being described as a wine and spirt dealer.

The next property along from the Gynn, beyond the open landscape of the fields is Warbrick Farm home of the Kirkhams and beyond that is Leys Farm occupied by the Butlers and much open land and fields in between before this, ‘breathing space’ of open land became prime, sought after building land. Later, on the 1901 census, Oliver is working as a barman at the Inn and a married daughter, Mary whose husband, a local lad John Sumner from Bispham, is also working there. By 1911 Alice is a widow and apart from her sister Elisabeth who is still living on the premises with her, there is only her son in law, John mentioned.

Alice would have been at the Inn for about 30 years until the building was scheduled for demolition and she was obliged to leave. In the brief obituary in the Lancashire Daily Post of 1933, it is claimed that the family had a history of 56 years in the licencing trade and she had come to Blackpool because of her husband’s ill health. On their marriage in 1873 her husband James is described as a driller, so he probably came into the licensing trade later (assuming that the occupation of ‘driller’ had no connection with the licensing trade) but perhaps with expertise to hand within the family from which to learn. James died in 1903 leaving Alice to run the pub with family help where her sons and son in law and, no doubt daughter too, worked on the premises at various times. She held the licence from 1896, after the purchase of the Inn and some of the land around it by Blackpool Council, until latterly at least, on a weekly tenancy to the last day of the Inn in May 1921. The Inn was then scheduled for demolition in 1925. With a severance payment of £130, she moved to 74 Newton Drive the address at which she died in 1933 at the age of 90 and in her ‘91st year’. On the 1931 electoral rolls there is an Alice Ashworth living along with a Mr and Mrs Burnett at 74 Newton Drive as indeed it is her address in the newspaper obituary. She is described here as, ‘To the last she astonished her family and friends with her nimble wit and shrewd observations of life.’ She would be remembered by her 40 year association with the whitewashed Gynn, ‘thirtyyears of which she held the licence there’ after the death of her husband. Her husband had died in 1903 so it was actually eighteen years that she had single handedly held the licence so there was a slight inaccuracy in the report there, unless her husband had been incapacitated and unable to manage the affairs himself before that date. Her body was taken back to her roots in Newchurch, Rossendale and buried there.

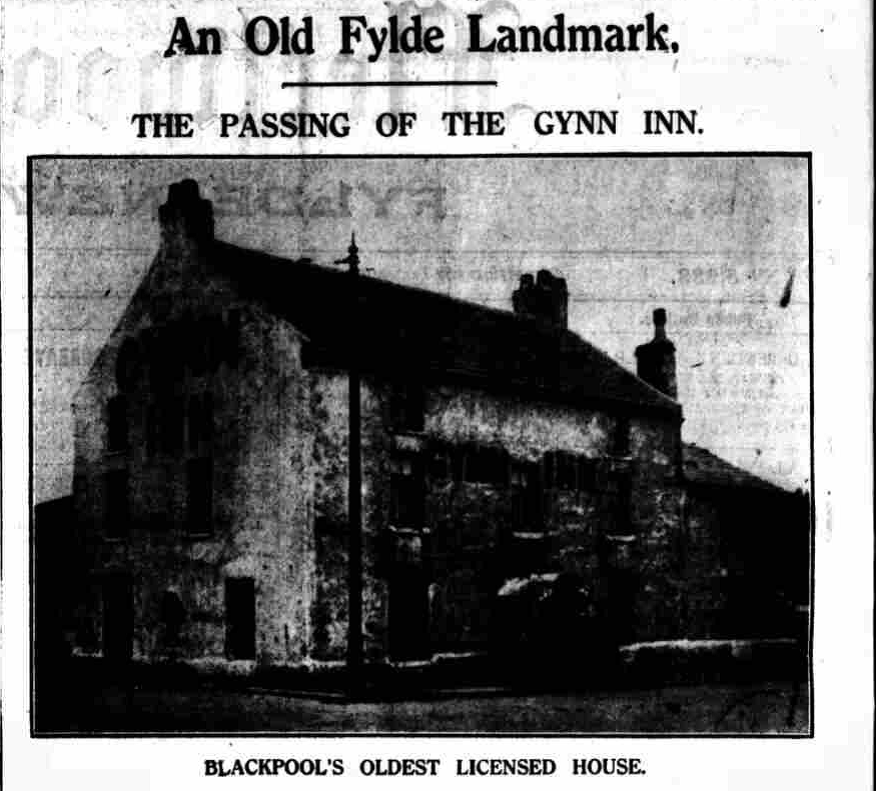

While the old pub is better represented in many another photograph as postcards, this is printed in the Fleetwood Chronicle of 6/5/1921. The demise of the pub, which had ceased to be a guest house, and presumably then only operated as a ‘pub,’ many years previously up to 1921, was not expected to be an item of regret despite the large amount of sentimentality attached to the longstanding history of its whitewashed walls. Today it might have been conserved if the cost of preservation would not be too much, but it was all in the cause of progress and was justified by the much needed public improvements in the area and Blackpool was developing and needed to expand beyond its boundaries. The coast northwards from the boundary with Bispham at the Gynn had already seen, in the first decade of the century, the collapse of a part of Uncle Tom’s Cabin into the sea and its demolition and rebuilding inland, and the transfer of its licence to the new property, and also the demise of the flea infested and shored-up Fanny Hall, both buildings comprising part of the Gynn estate. These buildings were a little further to the north from the Gynn Hotel which was situated nearer to the sea than the present, and more recent, building, and Uncle Tom’s at least within sight, and the chimney and curling smoke in evidence from of the Hall further away over the hill.

The original Gynn Inn of which Alice was the last licencee was closed down on Monday 2nd May 1921 and its licence transferred to the Savoy Hydro which had been built in 1914 and by 1920 was being extended. The story in the paper claims that the Gynn had been one of Blackpool’s most famous landmarks ‘its whitewashed cobblestone walls are familiar to thousands and thousands of visitors to Blackpool,’ and used to be one of Blackpool’s leading guesthouses. In its heyday it had accommodation for over thirty horses and was thus a strong focal point for many a visitor to the coast at the time. John Porter one of the area’s first published historians describes the Gynn as one of only a few houses in 1769 in the place known as Blackpool of which that and Bonny’s Hotel were the most important.

The Gynn House had been built, continued John Porter’s description, ‘near the extremity or the apex of a deep and wide fissure in the cliffs, formed a popular haunt during the season.’ John Porter was writing in the later 19th century (1877) when there was an established busy ‘season’ of summer health seekers underway by then.

The idiosyncrasies of the landlord at the time, continues the historian John, were demonstrated by the fact that he reckoned up the hotel bill to the departing guests on a horse block in front of the door with an added, ‘And sir’, (since it was no doubt the blokes as head of households who paid the bills) ‘remember the servants.’ The cost of a hotel at the time was 8d a day though it isn’t stated whether this was inclusive of meals but which, using an inflation calculator, would be about £60 in 2020.

John Porter then goes on to describe the storm of 1833, of which he would have had no personal memory and his father, a Preston man might not have known much either and which seems to have been a little enriched with imagination, (his History of the Fylde was first published in 1877 by his brother, so, in gathering his information might have included the imagination of others as the story was related to him.) The sudden and severe summer storm of that year (‘sometime during the summer of 1833’) caused havoc to the shipping off the coast and the shoreline became ‘strewn with the battered fragments’ of broken ships. While many ships lay marooned on the many hidden sand banks and others thrown onto the shore, one fortunate ‘Scotch’ (as written) sloop while battling with the gale and being drawn closer and closer to the shore and to its destruction, was suddenly given hope by a candle placed in the window of the Gynn House. It was this candle that was claimed to be the saviour of the sloop as it guided the vessel up the Gynn creek and thus the ‘exhausted sailors were saved from a dreadful death.’ It would have had to have been a clear and calm night for the detection of the candle in the window seen even from a short distance offshore and, if it had worked as efficiently as claimed, it would have precluded the need for research into lighthouse luminosity which was ever a focus of research during the 19th century and light house keepers would have only needed to order boxes of easily available candles instead of heavy, complex and expensive glass refractors which needed a constant vigil and maintenance, more so than a few candles. But then maybe there is a little truth in a legend if the real facts were made available.

The following morning it was noticed that eleven assorted vessels were lying in varying modes of helplessness and when the tide receded, the evidence of yet more shipwrecks was evident in the deeper waters. The following day three more, large and apparently waterlogged ships sailed past the coast. ‘Thus did the Gynn play a memorable part in one of the fiercest gales ever experienced on the Fylde Coast.’ (Fleetwood Chronicle May 6 1921.)

There is only one identified shipwreck for the year 1833 though no doubt many others are not recorded as not having been located or unable to be named before they were destroyed or scavenged for parts.

Gynn is nevertheless old English for ‘cleft’ and the vestige of this can be seen on the 1847 OS map where it drops below the 50 foot (15 metres) contour. The Gynn Hotel itself sits astride this contour, a lower benchmark on the building representing 48 feet and 2 inches in height (14½metres) from sea level. If this cleft appears to be devoid of water on this early map it is hard to imagine it had taken only fifteen years from 1833, however small the cleft might have been, to become dry land. The depression which afforded the description of the cleft is still evident today as the land drops in three directions from north, south and east to the centre which is now occupied by the roundabout, once the site of the old Inn.

The story of the end of the old Gynn coincides with the amalgamation of Bispham and Blackpool and it is as much to do with expanding Blackpool as it is to do with the receding cliffs of Bispham. As far back as 1901 Mr Hindle the surveyor for the Gynn estate was seeking a licence for a reconstructed room at Uncle Tom’s Cabin to replace the one that had been damaged and part fallen into the sea due to the erosion of the cliffs and to seek at the next Brewster sessions, then held at Kirkham, for permission to build a new hotel on the opposite side of the tram tracks. And in 1905 a Mr Blane, secretary of the Gynn Estate, formerly applied for a licence for the newly proposed building of the new Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the corner of Knowle Ave and King’s Drive as the existing Uncle Tom’s Cabin was in a dangerous state and part was collapsing in to the sea. Though the new licence was granted for the proposed new pub there was an objection that it would be too close the newly proposed Gynn Hotel. The Council had bought the old Gynn in 1896 and had its eye on developing the area which would include the demolition of the old Gynn Inn. But it seems that in 1903 the Council was willing to sell the Inn and gave notice to the potential purchaser that the deal must be completed within three months or there would be no deal. The Council still owned the Inn by 1914 so it is likely that a buyer had not been found. So it is evident then, that by the turn of the century, plans were at an early stage for the development of the area and the Gynn itself, having been there since 1745, was on borrowed time.

By 1914 Blackpool was looking to promote the future of its status as a prime holiday destination. Unaware of the modification to that status which the approaching war would bring, the Council was giving consideration for the first time to the new enterprise of providing deckchairs. Chairs were already provided through private enterprise but a good profit could be had on considering the returns from such enterprises in places like Brighton and Weston Super Mare.