Johnnie Hayes and the unusual story of the HMS Fidelity

31/12/2022 is the 80th anniversary of the sinking of the HMS Fidelity. When the ship was torpedoed and sunk, among the crew was Johnnie (Jack) Hayes, Blackpool resident and former pupil of Palatine school. He was 22 years old, not an unusually young age for forces personnel. He is commemorated at Portsmouth along with his shipmates and many other naval personnel. He was part of a remarkable story of the war, clouded in as much confused secrecy as possible at the time, and a story which, in the great spectacle of its curiosity, emerges every now and again having been told in book and film. This account focusses upon Johnnie Hayes’ involvement being, the Blackpool connection.

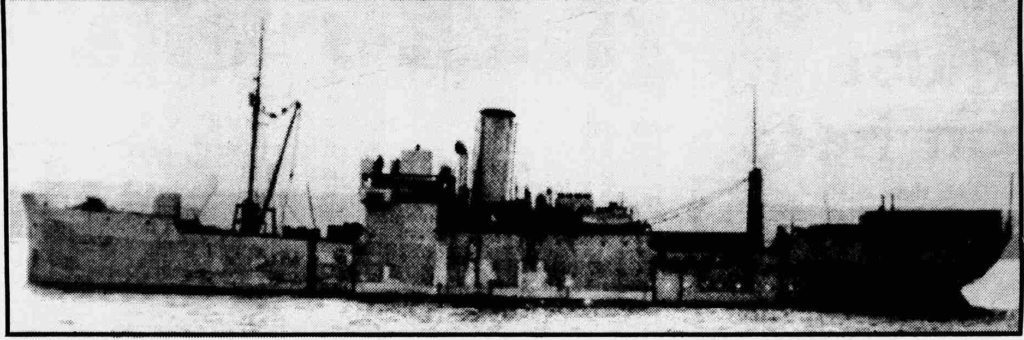

It was at 4.40pm on the last day of December and the end of the year of 1942 that the ship on which he was serving, the Special Services vessel, HMS Fidelity, was torpedoed by enemy action off the Azores and was sunk within a very short time. In the few minutes of its death throes, it was nevertheless defiantly able to send two depth charges towards the enemy position, though with no affect. The HMS Fidelity was no ordinary ship and it had a captain who was no ordinary captain who had a partner as First Officer who was no ordinary woman who, in being allowed through Admiralty regulations, was the only serving Wren officer, to serve and die on active service during the war. Referred to as the captain’s lover and, described as possessing the looks of Claudette Colbert, she was an enigma on board. She could use the two pistols she carried with her with the skills of Annie Oakley, and in both natural female form and behaviour, appeared to contrive a confusion of identity to the regular male.

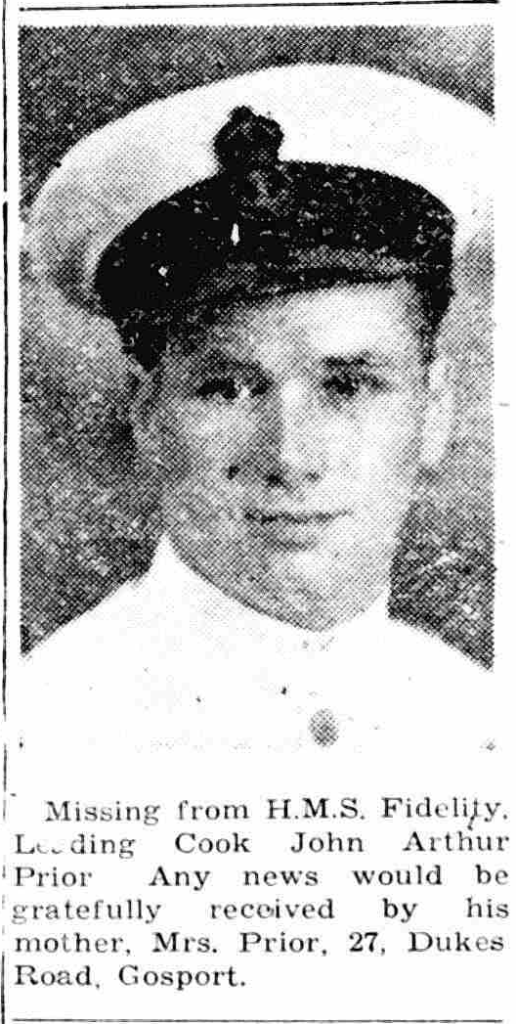

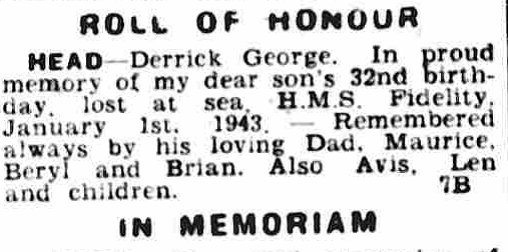

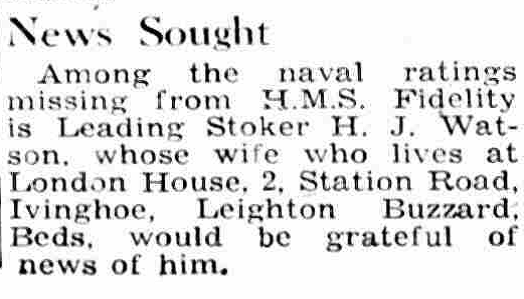

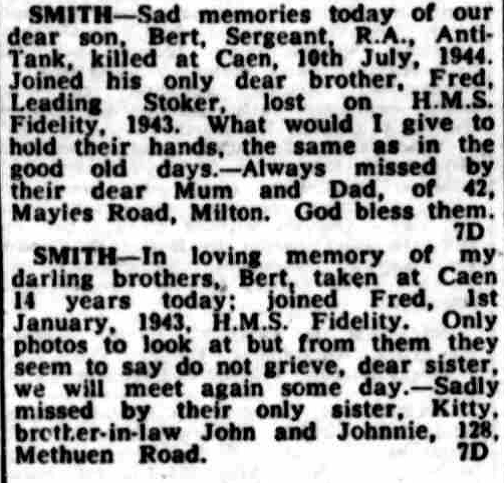

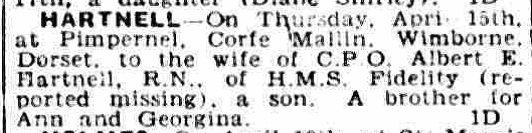

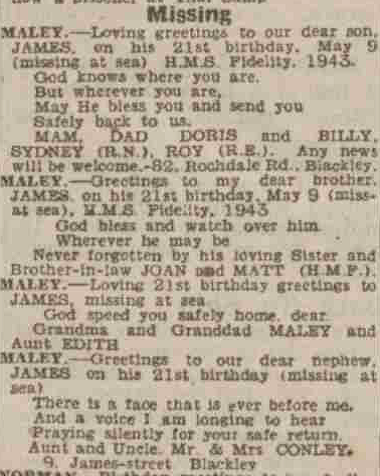

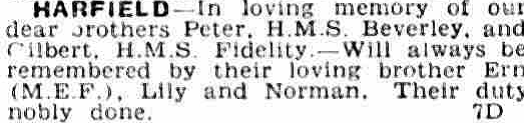

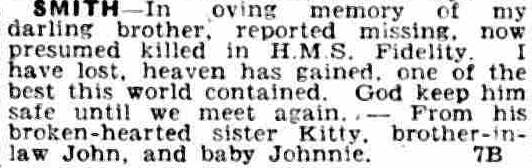

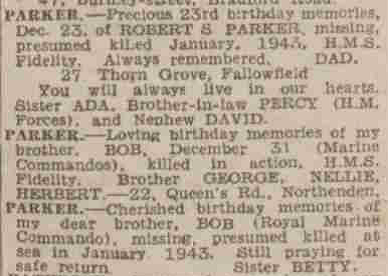

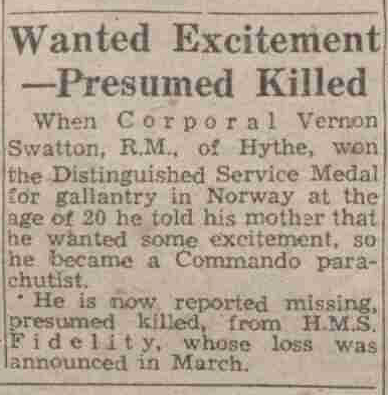

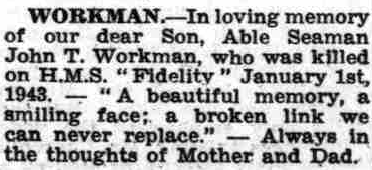

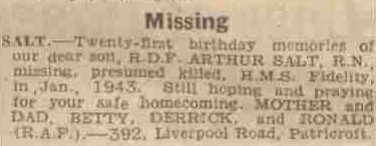

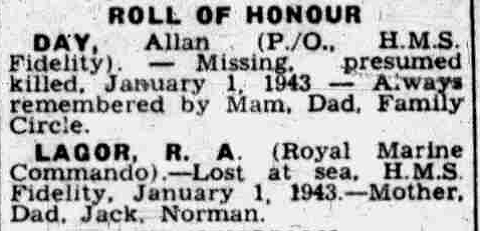

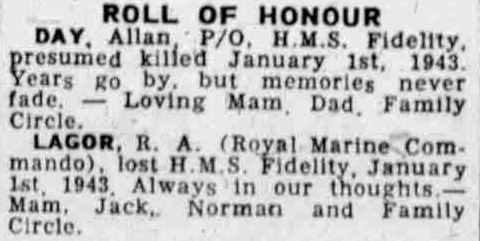

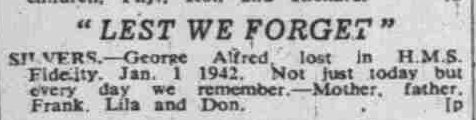

This account is being posted (31/12/2022) at the exact time that the ship met its fate, as recorded in the U-boat log on 4.40pm December 30th 1942, as a tribute to all those whose place it was to lose their lives during WW2. And, in the eternal conflict within the human being, it is to the friends and families of the same whose place it was to suffer that loss and live with it for ever after. In this particular incident, it is sympathy to the anxieties of those particular family members of the HMS Fidelity personnel who posted despairing requests in the personal columns of the newspapers for information in the months and even years, which turned into the decades, that followed, in their desperation to learn of the whereabouts or the fate of the men who had sailed away in the ship, and information which had been guardedly kept from them.

Though the story is well told since in memories and, books and newspaper reviews, sometimes in conflict with facts and sentiments, at the time it was a ship on an undisclosed mission to the Far East and information was jealously protected as highly sensitive at the topmost level – and for some observers it was protected for less legitimate reasons than the Admiralty was prepared to own up to.

Johnnie was an ordinary lad with nothing exceptional about him. Born in 1919 in Blackpool, to a Scottish mother and an Irish father, he attended Palatine School and, living on Clinton Ave, worked as an errand boy for the Co-op when his schooldays had come to an end. But a mundane job wasn’t enough for him. He wanted adventure. The 1930’s were increasing in age just as he was. The adrenalin of approaching war, of fighting for a just cause, was circulating through his veins. His father had been RN during WW1 and would be anxious about another developing conflict to which his two sons would be exposed. Johnnie had a younger brother, Peter.

Frank was Johnny’s best friend. The sketched memoirs of Johnny’s best friend in later life would present the opportunity to lift Johnny out of the obscurity that an early death at 22 years of age, had buried him within. Frank was an ordinary lad and there was nothing exceptional about him. From his home on Palatine road, he was at Palatine school with Johnny. His father and uncle had both been medics in WW1 on the Western front. He too possessed a strong sense of righteousness which allied itself to a defence of a national identity especially as the decade moved towards a seemingly inevitable war. Like many parents within that generation, the parents of both young men feared that their children should face the same dangers and hardships as they had experienced themselves. Johnny’s parents’ fears were not unfounded. They would lose both their sons, their only children, to the war

When Johnny and Frank, the two friends, were courting their girlfriends, each of whom would become their fiancées and then their wives, there were happy times for the foursome, in the short time they were going out together and dancing in the Tower Ballroom, a popular venue for many couples. The ballroom floor would eventually fill during wartime with uniformed men feeling proud and grand, and women at their attracting best distracting themselves from the uncertainties of the world outside at war. They were particularly happy times for Rita, Frank’s fiancée, and her war related work would have a happy irony placed within it on Johnny’s demise, though she was not privileged to learn of this during her lifetime, when the circumstances of Johnny’s demise and his identity on the HMS Fidelity came to light. Johnny would marry Ida late in 1941 and Frank would marry Rita in 1942. Johnny’s marriage would last a little more than a year, leaving Ida as a young widow. She would remarry some years later in 1948. Frank’s marriage would last much longer, into older age, when his memoirs would inadvertently assist in presenting the memory of his best friend to the world around him.

In 1937, Johnnie and Frank went down to London to join the RN, away from what they considered, in the excess energies of youth, their dead end jobs of riding bicycles with deliveries, Johnnie for the Co-op and Frank for a leather retailer on Central Drive. Johnny was taken on but Frank wasn’t, but he wasn’t put out for long, establishing a military service later on. He was deaf in one ear, the result of a pan of boiling water accidentally spilling over him from the cooker at a young age, but in another attempt at a military service he was able to part lip read his way, at first into the RAF, before other military service.

As Johnny had joined the RN, the first vessel he is known to have served on is the special services ship the Cape Sable, which had been requisitioned by the War Office in 1939, and Frank always believed that he had met his death on the sinking of that ship. But the Cape Sable survived the war. It was first employed as a ‘Q’ ship, those ships which were used as decoy ships and as a throwback to WW1 were used to land espionage personnel into enemy territory, but this role was eventually, and more easily and swiftly, effected by the use of aircraft. It was then in 1941 converted into an armed merchantman and now classed as SSF or Special Service Freighter. It is probable that Johnnie joined the crew at this time. It is first recorded as arriving at Scapa Flow on the 14th January 1942 where it ultimately left for the Norwegian coast from Sullom Voe and it was back at Scapa Flow on February 2nd. It was a very short trip, one which had to be cut short because its disguise had been rumbled while off Norway. It was helped from detection on its journey home by a continuing cover of dense fog. In April of the same year and probably reflecting this failure in principle, and after escorting convoy WN 42 to Rosyth from Sullom Voe, it was converted into an MOWT, Ministry of War Transport vessel. It is reasonable then to expect that Johnny was one of the crew members who then made the switch to the Fidelity for, reflecting the Gordon Mumford tribute to the Fidelity internet site, the account of a John Victor Goodall on that site states that Victor left the Cape Sable with others to join the Fidelity at the time of one of its conversions. John Hayes is on the crew list and commemorated at Portsmouth, an area from which many crew members originated. He is a Petty Officer for supplies as described both by the commemorative roll of honour at Portsmouth and by his friend Frank in his memoirs.

The captain of the HMS Fidelity had advised the crew at that time, that they would most likely not be coming back from their mission, or in the captain’s direct speech, ‘I am leading you to your death,’ but then the men who had joined the Cape Sable had been told the same before they set off, and they had come back alive so there was enough doubt to dispel fear by not believing. They had cheated death once so it could be cheated again with equal ease. And it was also more money.

On its final voyage, the HMS Fidelity was on a mission to the Far East for undisclosed sabotage activity, sailing via the Panama Canal, though another, less plausible, description puts it on its way to French Guiana in South America. For this purpose, and supplied with two landing craft, it had a company of Marines on board. Its captain and First Officer, as experienced saboteurs in the Far East were keen to get back to a place they knew well. The Captain had been born there and his co-saboteur and partner/lover, had been married to a plantation owner there. It was especially significant now that Japan had caused the USA to enter the war and they could make themselves useful in an area that was familiar to them. Frank had always thought that his friend had perished in the Far East. Many men from Blackpool died in that area of conflict before and after the fall of Singapore and some as POWs killed on Japanese transports by the mistaken friendly fire of a US submarine as Charles Hewitt, the brother-in-law of Frank’s brother, had been. But the Fidelity went down off the Azores. At the time of its sinking, the ship also had several men rescued from the water off the other ships within the North Atlantic convoy and that had been previously sunk by enemy submarine activity and which the HMS Fidelity was initially escorting to the safer waters closer to the American shores.

The captain of the ship was Jack Langlais, a Frenchman, whose real name was Claude Andre Peri with an execution warrant on his head issued by the French, Vichy Government. It has been claimed that the L’anglais in its meaning of ‘the Englishman’ came about when he needed a blood transfusion. He loved to fight and there was plenty to do at Gibraltar when he first arrived there and where he received an injury including a broken jaw. It was here that he received the blood of an Englishman, perhaps from a blood bank, or personal donors, if the account is accurate. He didn’t like the French because they had let him down. He preferred the English because they might not, and he always got his way with them. There were also other French crew members which included one woman, who was an explosives, cipher and sabotage expert and a cool hand with a gun. Like Claude, Madeleine Barclay whose legitimate French name was Madeleine Victorine Bayard, had an execution order upon her head. Claude and Madeleine were lovers though it doesn’t appear that there was anything starry eyed in their love match that might present a distraction to their military purpose, as their separate personal histories can be understood as moulding an insensitivity into them into as die-hard saboteurs. Their intimate association was kept from the crew on board and they had separate cabins (though at one time on the Fidelity, a shoe of Madeleine’s had been found underneath the captain’s bed by the unfortunate steward). Their job was stealth and deceit and their true relationship would have been relatively easy to disguise. There was no time or patience for the roles of star struck lovers between the two. They had a mutual connection and sexuality it seems was not there to distract beyond the brief, physical delight for either. At one time for a joke she had somewhat dispassionately and publicly painted black the testicles of the officers on board in a wardroom prank which was a giggle for all involved. Sex was, ostensibly a least, for practicality and not for love. Another time, when the hard faced and vindictive captain had ordered some of the crew to jump into the water off the ship in an expectation of loyalty to discipline, Madeleine had jumped in to rescue one who was in difficulties. She was completely naked as reported. In the time that the ship was under the command of the seemingly unstable Claude Peri, conditions were so bad that some crew members had jumped overboard in harbour to escape the severe discipline meted out. The steward, Jean Andries who filled the captain’s bath would be given a black eye if the water wasn’t hot enough and some who incurred the captain’s wrath for the most insignificant reasons were put in chains as punishment. They were confined to a place that was known as the ‘torture chamber’ where men were shackled and fed with bread and water for days on end, with a bottle of wine just out of reach and the picture of a naked woman on the wall opposite to tease. At one time when an officer attempted to retaliate after being punched by the captain, Madeleine pointed a gun at him to protect her friend and lover. One officer had had enough and committed suicide by shooting himself. Such was the unusual nature of the ship that later, post war conjecture attempted to reason why the Admiralty, which included the assumed acceptance of both Mountbatten as head of combined operations and Winston Churchill, had maintained a high level of secrecy over the vessel.

Anyone French on board (or off board if on saboteur duty) had a death sentence hanging over them which had been issued by the Vichy Government. Patrick O’Leary, the only man who could get close to the fierce and pugnacious captain Jack Langlais in trust, was Belgian, real name Albert Guerisse and had joined the ship at Gibraltar. All the French crew carried English names as noms de guerre to disguise an identity. Pat O’Leary, as a former, second in command on the Fidelity, and renowned for his escape routes through enemy occupied territory, recounted his experiences on the BBC programme, ‘This is Your Life’ some time later, before the quietly spoken Eamon Andrews. As a source of information, however, his facts as recounted in a book published in 1957 are occasionally at odds in detail with that used for much of the source for this narrative of Claude and Madeleine and the Fidelity itself.

Claude had an intense hatred for this French Vichy Government which he believed had let his countrymen and his nation down in its capitulation and appeasement to its German invaders in 1940. Claude and Madeleine, each who had their own spectacular stories to tell, had been recalled to Paris from saboteur activity in French controlled Vietnam, and they had left the capital with instructions from Le Deuxieme Bureau, French Intelligence, to join the SS Le Rhin, (which would later become the HMS Fidelity), at harbour in Marseille, and to conduct disruptive saboteur activity within the scope of the vessel against the then current enemy, Germany. This was carried out effectively and Claude and an engineer from the vessel, both being strong swimmers, had blown up with an explosive charge placed on the hull of an enemy ship moored at Las Palmas.

Returning to Marseilles and then to Paris they had left once more during the exodus of its citizens from the French capital before this German incursion and takeover and subsequent capitulation of the French Government. Claude, a saboteur extraordinaire, with his partner in destruction, Madeleine had with them a small amount of plastic explosives, a new concept in destruction and unknown to the enemy, and highly useful in saboteur activity as demonstrated to British Intelligence in England when they arrived there. This plastic explosive, to the alarm, of British Intelligence when presented to them, had nonchalantly been stored under Madeleine’s bed in her cabin. Though she assured British intelligence that it had been perfectly safe, they were perhaps unaware that Madeleine shared a bed with Claude in another cabin.

Regarding Blackpool, Johnnie’s home town, there is the grave in the Layton Cemetery of Benoit Desquesnes who had been imprisoned and then exiled to England by Napoleon 3rd nearly a hundred years earlier for his anti-Government beliefs. Each year however, and only in coincidence connected to the moment of this story, his home town of Maroilles in Northern France commemorates in period costume the 1940 citizens’ exodus from Paris.

Claude Peri had been born in French colonial Vietnam when Vietnamese culture had been, often crudely, replaced by French culture in architecture and manners. His upbringing was disrupted and middle class. His father was a telecommunications engineer, constructing a network within the country. Claude had many influential friends there. But as much as colonialism might bring advantages to the colonisers these were at a cost to the indigenous population which was treated, while working the profitable rubber plantations, as those brought in to the Americas from the African continent by Europeans This repressed workforce was soon to become restless towards rebellion when plantation owners were attacked, murdered and buildings set afire. To this effect Claude had begun to work in espionage. The story as it appears to be true, is that he had met Madeleine as he had gone to investigate the destruction of a plantation and found some out buildings burned down. Inside the intact yet ransacked owner’s residence, the corpse of the owner was slumped at his blood be-smattered desk. He had been shot through the head. Under the desk was a young woman, the wife, cowering and whom he would later learn to be Madeleine. She had been raped multiple times.

The French would eventually lose their foothold in Vietnam after the military defeat at Dien Bien Phu just over a decade later and about another decade after that, the fear of the spread of communism would entice the Americans in, in an attempt to reclaim it.

Neither Claude nor Madeleine had seen too much love in their lives, and meeting like this perhaps constituted a moment of spiritual union. From this less than usual introduction for two people, they became companions and eventually lovers as much as the word describes the physical union of two people. Their selective and limited compassion for the rest of humanity made for a good partnership in espionage and sabotage. Already hardened to life, sentimentality was perhaps only for fools or for the weak.

Madeline Bayard was born in Paris to a seamstress mother. It was at the surge of the French, Parisian fashion industry as the first decade of the twentieth century drew to a close and when outworkers like her mother had to work their fingers to the bones in order to scrape a living. They were easy meat for the predatory male, and had a reputation for being willingly sexually available for a small price. Her mother had a few children as a result but most did not survive the rough and often insanitary living conditions when disease was most easily spread. Madeleine was given away at birth where there was no hope or ability to cope for a disadvantaged mother. When adult, Madeleine had met and married a man who owned a rubber plantation in French controlled Vietnam and went to live with him there. Johnnie’s friend Rita had been given away at birth as had Frank’s elder brother, for part, similar reasons emerging from the destruction to families meted out by WW1, and in a coincidental manner Rita was inadvertently and unwittingly able to avenge not only Johnnie Hayes but, in a distant and circuitous manner, the abused femininity of Madeleine herself in an adult life in which her own adult femininity was expressed and fulfilled with mutual respect.

After meeting up, both Claude and Madeleine might have conjoined in a kind of mutually cold dispassion for life somewhat separated from their fellow human beings, and they became partners in espionage and sabotage. Being schooled in the use of firearms and explosives, their first significant assignment was to blow up a Japanese ordnance warehouse in China. Claude then left for Paris as he had been invited to Intelligence headquarters for briefing and returned in a gruelling overland journey by car, meeting up with Madeleine again, first in Bangkok and then eventually getting together in Hanoi when they continued their espionage activities. On the outbreak of war they returned to Paris to work with the Intelligence services when they were then assigned to the SS Le Rhin, docked at Marseilles, to conduct sabotage in the Mediterranean and beyond.

Once the two saboteurs had left Paris for the last time they had with them that quantity of highly valued and innovative, plastic explosives a concept unknown to the then German enemy. Claude was confident and uncompromising and could bully anyone with impunity whether it was a crew member who needed a thumping or the Intelligence Services that had to largely give in to what he wanted, (like having Madeleine on board). Once at Marseille, it was not difficult for him to convince the warehouse clerks that he had permissions to load up with whatever he wanted or, that what he was taking without their permission, was legitimate and which included foodstuffs, clothing, bicycles, small arms and ammunition. The SS Le Rhin, was a vessel that had been built in Liverpool (another source claims Hartlepool) and bought by a French commercial concern.

When the ship sailed for the last time from Marseilles, it was under the orders of Claude and not the captain and its destination was ostensibly Algeria. But Claude took his own course when it pleased him, to the curiosity of the crew, and eventually sailed into the harbour at Gibraltar after the news of the French capitulation to Germany was announced and the choice of the mixed, French speaking international crew had to be a loyalty to one or the other. Anyone pro-Vichy, and who would have preferred to sail to Algeria to be under the French flag, was sent off the ship with violence if necessary and a new crew had to be searched out and found in and around Gibraltar, sometimes with a little persuasion a la the king’s penny as was 16 year old Jean Andries. At this time the crew was enriched by the arrival of several Belgian army officers who had evacuated from France and which included Albert Guerisse. Here, Claude the tough talking, violent, uncompromising man and always seeming to get what he wanted from British intelligence, perhaps because they knew he was a man who would die before giving in to anything. Because he was able to get away seemingly so easily with his demands to the British Admiralty and Intelligence, like having a woman on board, it inspired the later opinion that the sinking of the Fidelity ‘ended the most embarrassing incident of the war’ because a woman had been legitimately allowed on board an RN vessel. Despite all her skills and bravery and contribution, all that ‘this woman’ Madeleine was now renowned for at this later time a little more than decade afterwards, was for wearing black bloomers as the ‘Buccaneer in Black Bloomers’, something that had to be assumed via navy regulations but never proven by the large, bold, newspaper’s readership-seeking headlines.

Having arrived at Gibraltar, Claude’s instructions from the French Government, which had still expected his loyalty, was now to blow up the largest battleship in the British fleet which was the HMS Hood and which was expected in harbour soon. But he was Free French now and had listened intentlthe y to the broadcasts of De Gaulle deploring the capitulation of his nation. He allied himself and his ship with Britain and was ultimately taken there, where the vessel was docked, refurbished and first modified into a Special Services vessel at Barry dockyard South Wales. And it was re-named the HMS Fidelity.

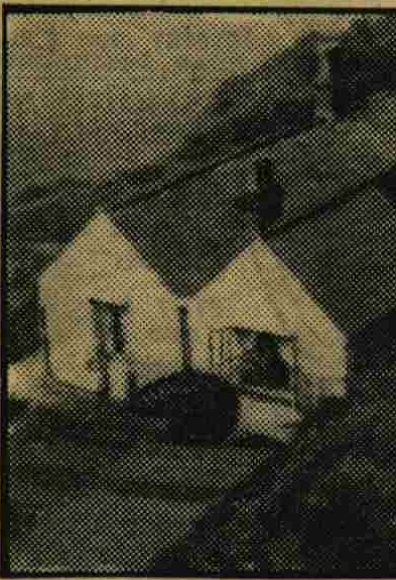

Here the ship was unloaded of all the booty from the docks at Marseilles and sold on for a good price. For the several months that the ship was undergoing a refit, the crew was accommodated at the Barry Docks Hotel and the Windsor Hotel, while Claude and Madeleine rented a house at Well Walk, Cold Knapp. With the crew and the dockers mixing, the strange nature of the ship became evident in dockside and bar side conservations. It was indeed an unusual ship with an unusual crew. Some of this crew went on to marry local women, bigamously on occasion, it was alleged.

Before a second and more comprehensive re-fitment at both Merseyside and Southampton which included the provision of guns, two torpedo boats and a sea plane all well disguised on deck, the Fidelity took on two, largely unsuccessful, missions to the Mediterranean to land agents in France and pick up escapees helped by the French resistance, disguised initially as a neutral Portuguese ship and to do as much damage as it could to the enemy en route. The Fidelity was an improvement on the previously equivalent and less successful Q ships, as the Cape Sable had originally been, though the missions it conducted did not have a great deal of success. While these ships could maintain their disguise from a distance, close to however, their ruse could be easily found out especially from a ship too close or a low flying aeroplane. But this appeared to be meat and drink to the captain and his eager and equally capable partner.

The importance of a disguised vessel was to continue the disguise if it meant re-painting the ship in mid-ocean and flying whatever national flag was suitable for the occasion. In this respect on occasion, Claude had insisted the men dress as women and sit upon the deck. While Madeleine with her reputed Claudette Colbert looks was self-evident as female, the men were obliged to cover up their hairy legs and turn their bearded faces inwards so the observers from a passing ship or an aircraft might only see a merchant ship. And it worked on more than one occasion as a generous supply of women’s clothes had been brought aboard for just that purpose. It also worked while the ship was at Liverpool when a few of the cross-dressed men were asked to parade around the deck. From a distance the cat calls and wolf whistling from another ship were aimed at these women but when a few of these were allowed on board, a surprise was in store for them. It was the kind of vindictive humour that Claude, and indeed Madeleine, as ‘une peintre de testicules’ it might be evident, were not averse to.

Claude however did have access to a concept of sentiment somewhere deep within him even if it was in the coldness of his heart as a technicality, as he had admired the Taj Mahal on his overland journey to Vietnam from Paris. Here, he declared his admiration for the strength of that human commitment to fidelity, that quality being the motive for its construction in this case in cruel and uncompromising manner, and possibly was the cold sentiment that attached itself to the ship’s name and that would take his own concept of fidelity to the grave with him. It was sentiment that he could never express in public himself only in the self-confessed commitment of ‘Honneur ne cherche, fidele je suis’. Or indeed Madeleine it would seem who had had that sentiment brutally ripped out of her in her adult life if there was ever an element of it left to survive from the difficulties of an early life.

While in Britain and while the ship was being refitted and disguised, both Claude and Madeleine took further training in Scotland and the Isle of White along with a detachment of Marines, and Madeleine also attended Wren officers headquarters at Greenwich and elsewhere for training. Here in the Isle of White she shared a cottage near Ventnor with Claude in what would have been ostensibly the closest to a normal life they would have ever been able to share together.

The Fidelity set off for what would be its final voyage at the end of November, now with ex Palatine schoolboy Johnnie Hayes and his friends from the Cape Sable on board, to join the North Atlantic convoy ONS 154 which had started off from Liverpool. Even the Irish Sea was a dangerous place for shipping as it was patrolled by enemy U-boats as the Fleetwood trawlermen could avow in both wars with alarming stories of fighting back with their own guns. In WW1 they were fitted with guns with naval personnel to operate them, and as an incident in early WW2, being left in an open boat without food, water or warm clothing to find land after ‘graciously’ being hurriedly allowed to leave their boat to fend for themselves, and then seeing from their position in their open boat, their trawler with all their personal belongings upon it, blown up by the enemy.

In the Atlantic, the convoy was constantly attacked by consorted U-boat activity and several ships were sunk when the Fidelity had to take on survivors out of the sea from one of them. As the Fidelity was approaching the Azores, the engine began to malfunction and slowed down the vessel and so the captain decided to pull up the protective torpedo nets to maintain some sort of speed. One of the motor torpedo boats was already off the boat hunting, and the sea plane was ordered to set off too but suffered damage (in doing so it is reported that it hit the hull of the Fidelity and thus caused the damage that forced it to slow down). To the prying eyes of the submarine periscopes this was an obvious sign that the vessel within its sights was a disguised merchantman and so a necessary target. Several torpedoes were launched during the day at the ship, the first ones not being successful, but at 4.40pm the torpedoes left the submarine U-435 and at least one of them found its target. The depth charges that were fired back towards the submarine attacker landed safely away from it and the motor torpedo boat was far away. The overcrowded vessel went down quite quickly leaving many men in the water. Since the vessel was considered a spy ship and orders from High Command, in not as many words, were to leave no prisoners, it is believed that the surviving men swimming or clinging onto anything that floated were sentenced to death, if not left to drown, then by machine gun fire as was that intimation of instruction from the highest enemy command. No trace of the vessel, and no survivors from the U-boat attack were ever found by the RN vessels that searched the area for some time almost immediately afterwards. The log of the U-boat commandant quotes that there were several hundred survivors in the water after the sinking which adds credence to the fact that the commands of the higher authority were carried out. Unlike the Fleetwood fishermen in their own, severe hardships, these men didn’t get home.

The eight crew in the motor torpedo boat however, who had picked up the two man crew of the seaplane, eventually made it home having been picked up by an RN vessel on the way, using their shirts as sails at one time as their engine also had failed, the only survivors and the only ones to tell the tale as much as they were allowed to as it seems that they were held to secrecy on their return home.

Whether Claude Peri faced certain death with the exhilaration of triumph to fidelity or whether he succumbed to the natural fear of death in the human being will never be known. Perhaps the inevitably of death was no big deal for Madeleine either or perhaps at the final moment she regretted a life which fairer circumstance could have made much better.

If that execution was the end of many of the men and the one woman, it would have been the end of Johnnie too. As a petty officer responsible for supply, he may have been below decks when the torpedo struck and thus not have been able to get to the surface, so would have drowned in the claustrophobia of the below decks with no means of escape. Had he been able to get to the surface and escape the ship it seems evident he would have been shot as he struggled to keep afloat on whatever he could find to cling on to in the cold water. Perhaps, if below deck he was thinking of Ida or perhaps he had no time to think in the desperation of survival as breath was denied him as the water pressed in him denying the air to his lungs.

Eventually Johnnie and his shipmates would be commemorated on a memorial at Portsmouth. The plaque reads; HAYES, supply P.O. JOHN P/MX. 55412. R.N. HMS Fidelity. 1st January, 1943. Panel 79, Column 1.

Those who died; crew 274; 44 survivors from HMS Shackleton picked up from lifeboats; 51 Marines.

Mtb; 8 crew survived and two from the crashed seaplane which they had picked up from the sea, and all later picked up by an RN vessel. An obituary of George Eady in the Press and Journal (Orkney and Shetland edition) of July 1st 1999 states that now at 75 years of age he had formerly served in the RN during WW2 and was left drifting in an open boat after the HMS Fidelity had been sunk, so it might be assumed that he was one of these survivors. He lived to be influential in further education at the College of Commerce in Aberdeen.

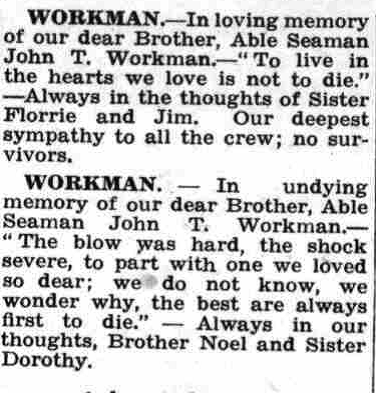

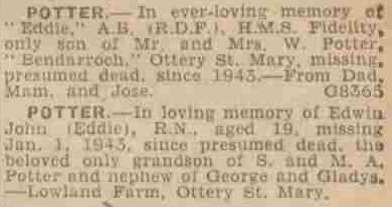

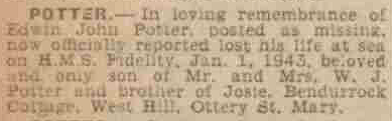

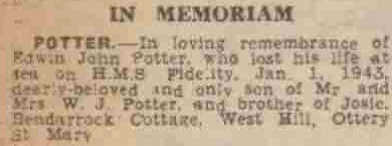

Back home the clandestine nature of the Fidelity was kept from public knowledge and no information was available to the families and friends of the men. It was not until the 17th March that the Admiralty announced the loss of the auxiliary warship. ‘Her Commanding Officer was a member of the Free French forces. Next of kin have been informed.’ The Daily Herald March 18th 1943 reporting the news of the previous day’s announcement. Assumed sunk, it didn’t announce that it had been sunk, but somewhat and inevitably euphemistically as lost, which meant that there were those relatives who clung on to hope for a long time afterwards. Perhaps they had been taken prisoner and were still alive. Hope is eternal for some as the appeals and commemorations in the personal columns reveal. In the months and years afterwards, the newspapers continued to print adds in the personal columns as desperate relatives sought information of the demise of their sons, husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles etc.

Johnnie’s wife Ida would not have found out the fate of her husband of just over a year, for quite some time.

From then and to this day, the story of the Fidelity has been one of curiosity and conspiracy. Could either Mountbatten or indeed Winston Churchill have prevented its sailing with what had been described as a psychologically unstable captain and could the Admiralty and the secret service admit at the time that there was a woman on board which was considered bad luck and which was against navy practice?

Attached are newspaper inclusions of the desperate families clinging on to hope and then despairing. The dead no longer have to suffer but the living and the generations they produce do because the consequences can reach far forwards into the future. There is always a lasting tribute to those who died but less to those who had to bear the loss and have been condemned to suffer in life. Nancy Savage, the sister of 17 year old stoker Arthur Noon who spent her life wanting to know how her brother died inspired the subject of a new book published by Peter Kingswell, ‘Fidelity Will Haunt Me Till I Die.’ Royal Marine Historical Society 1991. Likewise by 1999 George Millar wanted to know the truth about how his brother had died. Records are released 100 years after the birth of the serving individual. If the service records of many will be available now, many stories can perhaps be revealed.

But as early as 1956, after a blue book on naval discipline had been published, it inspired a Frenchman Marcel Jullian to write a book much of which was based on the personal memories of Pat O’Leary and Lieutenant George Archibald. In this book, Claude Peri is described as a Corsican and a pirate with references to a delusions toward Napoleon, as ‘La Corse’ in his tyranny. In the book, Jean Andries known as John Owen on the ship as his nom de guerre, and later to settle and become an optician in Norwich, had been the personal assistant of both Claude and Madeleine on board the Fidelity before the last, fatal journey and had suffered a lot of punishment, and many a black eye, from the captain including being chained in the ‘torture room’ for allegedly two weeks with a limited food supply. It was he who had been struck for preparing a tepid bath, rather than a warm one for the captain. He hadn’t been the only one to have been treated this way. He survived, a couple escaped at Gibraltar by jumping ship, but one officer committed suicide by shooting himself. Johnnie Hayes would have escaped this kind of punishment no doubt as it was alleged that the captain, in his unusual hatred of French, would never hit an Englishman.

For Madeleine herself, she was described as that ‘Buccaneer in Black Bloomers’ in a large headline font on an almost full page article in the Sunday Pictorial of 1956 as a personal version of the story of the Fidelity is written by someone who had met her in person and who knew bits of the story but not all. Knickers seem to create more excitement in the male than do underpants in the female and the fact that naval uniform regulations required Wren Officers to wear blackout bloomers under the uniform made for good readership capturing headlines, but diminishes the true story of the person and her shipmates who lost their lives alongside her. What is interesting is that the inference from the large ‘blue’ book on naval discipline published in that year, in which Madeleine was mentioned, and in the opinion of the writer of the above opinion, is that the navy were too ‘red faced’ to admit to the fact that there was a woman officer on board and that’s what all the secrecy was about. At least she was described as a heroine at the end of the article but then concludes in a reference to her knickers, in bold and capital font, as she was the ‘Navy’s first and perhaps last Buccaneer in Bloomers’. The writer, Paul Boyle, ex RNVR and with less control over the journalism of the newspaper article, states that for the last ten years he had not been allowed by the Admiralty to reveal what he knew about the Fidelity.

Postscript

But it was not the end of coincidence in a kind of avenging circumstance which reveals itself later. As a twist of fate, and a naturally justified human emotion of vengeance, it was a Wellington bomber flying out of Gibraltar that eventually took out the U-boat that had sunk the Fidelity. But this would not have been known to Ida, nor to his friend Rita, now married to his best mate Frank, and who had worked at the Vickers factory in Blackpool where Wellington bombers were constructed. If there had been even a tiny piece of that aircraft that had seen Blackpool, (there were factories in Stourbridge and Cheshire) and that she had handled, it could be said that it had avenged the death of a friend and, for Blackpool itself, one of its sons. Rita had worked for a short time at the Squires Gate factory but in her natural state found it difficult to cope with the night shift in her effort to stay awake. But more than that as a shy and reserved young woman with a natural scepticism of friendships due to her earlier, difficult childhood experiences, she found the not unusual sexual pressures and expectations of the night shift too much for her so she left and joined the AFS.

Frank in his time with the RAF was also associated with Wellington bombers as well as that other workhorse, with so much expected of them in the early part of the war, the Blenheim. The very first of the Wellington bombers, which somewhat affectionately came to be known as a ‘Wimpeys’, ostensibly after the Popeye character but possibly and anecdotally a little more contorted, and mildly crude even, was produced at Stourbridge. The very last one was produced at the Vickers Armstrong factory at Squires Gate, Blackpool, a Mark X and No 11,461 that number being the total number of Wellingtons produced. At the end of production, on the 15th of October 1945, the bomber was taken for a test flight and after this successful flight, the Mayor and Mayoress and Council members were taken for a celebratory flight in an expression of civic pride.

On the occasion, a stainless steel replica of the aircraft was presented to the Council but this seems to have been lost since.

The Wellington bombers had a heroic history in the war, not only as bombers but with a versatility that encompassed many other duties. They conducted the first raid on enemy shipping the day after war had been declared. But with less speed and less attainable height, like the Blenheims, they took the brunt of the fighting especially before the large four engined and more memorable and romanticised aircraft came off the production lines. Some Wellingtons were fitted with Leigh Lights to aid in the searching out submarines in the dark and in the case of U-415, the one that had caused the demise of the HMS Fidelity, it was the Wellington that had spotted it and ended its service.

Johnny had a younger brother, Peter Mill Hayes (Mill being his mother’s pre-married name). Almost a year to the day after his brother was reported missing, Peter set off from the Melbourne airstrip in Yorkshire in his Halifax aircraft as co-pilot but, as in the case of the Blenheims which Frank had been attached to, the weather was fine and without cloud cover, the attacking planes were an easy target from the ground when over Germany. Peter’s Halifax was shot down and he was killed on 20th of December 1943 but, unlike his brother, the aircrews, as mutually respected adversaries, received a respectful burial and a gun salute.

Peter left a wife Catherine. Cwgc shows Peter as No 10 Squadron Volunteer Reserve. He is buried at Rheinberg and his age is given as 29 years old though his birth date is actually 13/1/1922 which would make him 23 years old.

On the Christmas day of 1942 Mr and Mrs John and Catherine Hayes had two sons. On the following Christmas day of 1943 they had none.

The Wellingtons were workhorses like the Blenheims. Frank worked with Blenheims in Squadron 82 but he was ground crew. Frank’s father had proudly seen his son off on the train to join the RAF but once the dangers of war were looming, he promptly alerted the authorities about his partial deafness. Invalided out, he then he joined the fire service and then the Grenadier Guards from which he was seconded back to the fire service for the extent of the Blitzes. The Blackpool fire crews were needed in both Manchester and Liverpool and would also relieve the London crews who came to Blackpool for a rest after an interminable and torrid time without a break in the capital as the buildings continued to burn and fall and casualties were consistently high. At this time, the city of Liverpool could be seen burning from the rooftops of Blackpool. A somewhat laborious and energetic job for the fire watchers when allocated, was to climb to the top of the Tower without using the lifts at the beginning of the shift and all the way back down again at the end of the shift.

Frank had been in 82 (B) squadron of Bristol Blenheims. In 1940 after his medical dismissal from the service the previous autumn the squadron was wiped out twice, once over Denmark and again over Northern France a month later. As ground crew, he was lucky not to be among the flight crews of that Squadron. Some were killed, some severely injured, some captured, some with amazing escape stories to tell, one a friend of Frank’s later killed, who was initially up for court martial but then reprieved, for turning back with a faulty engine. There are several photographs of the demise of the airmen and the respect their adversaries administered to them, a military funeral from the enemy, and a 36 gun salute at the graveside. In some coincidence, there is a John Hayes on one of the crosses. It is a different respect administered to an enemy than that delivered to Johnnie Hayes and his shipmates and crew.

Frank remembers the men who were his friends, close in deed and conversation in legitimate grumbling about food and conditions and machoism in the organic sexism of the era. And when a Wellington bomber with a female pilot had ditched in the Mediterranean, it was only ‘a pity about the aircraft’. The pilot was rescued from the sea and so the men perhaps felt they could afford the dig at her. It would have been different if she had been killed, it would be hoped.

13 of the men, of average age in their early twenties, downed in the Blenhiems over France, survived to become prisoners of war though such is the irony of misfortune that one was killed by friendly fire in a marching column of Pows mistaken for marching enemy troops a few moments before the end of the war. Friendly fire was most probably the cause of death earlier in the same year of 1940, of that other female pilot that most celebrated of female aviatrices, Amy Johnson, one of many but who had a strong Blackpool connection, leaving her sister’s house in the town for the last time, and crashing to her death in the Thames, suspiciously but not confirmed, a victim of friendly fire. Such is luck, or the lack of it and which at that time for that generation, could dictate whether it was life or death that was presented to you.

The Newspaper Inclusions.

In memory of those who died and those who lived to suffer the loss.

Sources and acknowledgements.

The indication that Johnnie Hayes was on the HMS Fidelity comes from Frank’s memoirs and had Johnny on the Cape Sable. Frank Reed is my father. Rita is my mother. The HMS Fidelity website forum shows that many men went from the Cape Sable to the Fidelity. There is a Johnny Hayes on the crew list. The commemoration is at Portsmouth.

The story of Claude and Madeleine is largely taken from ‘Claude and Madeleine’ by Edward Marriot, published by Picador in 2005. Other information from online sites described below. A book written in 1957, ‘The HMS Fidelity’, (Wat at Sea) the first time it seems that those involved and survived were allowed to tell their stories, was published by Marcel Jullian, Souvenir Press. I have taken reviews of this from the contemporary newspapers. The story of the Bristol Blenheims is revealed in ‘The Squadron That Died Twice’ by Gordon Thorburn and published by John Blake. The story of 82 Squadron was influenced by Frank’s assignment to that squadron on first joining the RAF and his subsequent memoirs of the same up to August 1939.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive via Findmypast. for all newspaper extracts.

https://2ndww.blogspot.com/2016/04/personal-memories-of-hms-fidelity.html

HMS Fidelity and convoy ONS 154 part 2 – Wydawnictwo wojskowne ZBIAM

https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?17199

https://www.wrecksite.eu/refPosView.aspx?183789

https://www.specialforcesroh.com/index.php?tags/hms-fidelity/

https://2ndww.blogspot.com/2016/04/personal-memories-of-hms-fidelity.html

A very fascinating article, my late Great Uncle Wallace Garland sadly was lost at sea on HMS Fidelity also. Recently I visited Portsmouth to locate his name on the Naval Memorial.

Thanks for your comment which adds another important person in name to the picture. I see your great uncle was a blacksmith on board (CWGC).

Regards

Colin Reed

Thank you, very interesting article.

My great uncle, Cyril Jones P/SSX 31225 – Act. Ldg. Seaman, was lost on Fidelity. He had previously survived the sinking of HMS Barham in Nov 1941.

Thanks. The Fidelity has a fascinating story but a very tragic one and all the families suffered for a long time afterwards in not knowing what happened.

My Uncle, Thomas Moreland was also aboard, it would be wonderful to get greater clarity, hopefully over the coming years it may become easier for the next generation once more records are released. A great article.

Yes, I think that would represent a kind of closure to the unknown fates of those aboard. Too late for those intimately involved, but closure of a kind nonetheless.

A great read and thank you for sharing my uncle Peter Goodall was also killed on HMS Fidelity and we keep trying to find more information we have visited Portsmouth to see the memorial

Thanks for your comment and information. It seems there was so much information kept secret and so many families left without that necessary closure. Though the story is entitled with one man’s name, it is equally about everybody on the vessel at that time, and about those families left with so many questions afterwards.