Blackpool in the 1850’s; Kickstart to the modern town

THE BIRTH AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE FIRST PROMENADE, THE DEFINITION OF THE TOWN, THE FIRST PARLIAMENTARY IMPROVEMENT BILL, THE CRIMEAN WAR, THE BRIDGE OF PEACE

Forward

Blackpool is my home town. My patronymic arrived during the frantically patriotic days of the First World War, as thousands of recruits arrived to fill up the available accommodation and to train on the beaches here. It has been recorded (and probably still relevant) that Blackpool has the least indigenous population in the country so we’re a mixed bunch here, really. And that goes for Britain as a whole though perhaps not to the extent of Blackpool. 90% of the information provided here has come from the newspapers. Any other, external sources of information to add to a prior understanding of British and European 19th century history, some years in archaeology and my own, family history research, that I have used to fill out or confirm detail, I have acknowledged at the end. Often it’s not new information, but it is how the hundreds of newspaper articles of the middle decade of the nineteenth century (and a little before and after it) have viewed Blackpool for better or worse.

PRELUDE

The story of the modern town begins in the 1850’s though the place has existed in geological and climatological time for long before that. The human geography has also been around since before recorded time but kicks in as a holiday place when the very first door in the area considered as Blackpool was opened to accept a visitor for hospitality or profit. From that time, generations of people that have come not only for the fresh and health giving air, but also to experience the vast open space of the sea, to enjoy the entertainment, to throw off the cares of living, (which doesn’t always include getting blind drunk) and at times to escape from the horrors of warfare or political oppression. They have all given the town a reason to exist. As well as in the savage conflict of war, it has also served as a place to train the soldier on the expanses of its beaches as well as providing a place to heal the same physically and mentally broken soldier on his return. In a time of need, every door has been thrown open, and every bit of space made available for the cause of the nation.

In the 1850’s it had even been a place of refuge when the end of the world was nigh, as a comet hurled its destructive way towards the earth. It missed, of course, otherwise I wouldn’t be writing this.

The geographical position of the town is the reason why it had begun ultimately as a place to have a break or take an extended holiday, or later, a place where you could go to fill the choked up lungs with air of a vibrant freshness that the dirty cities could not provide, elements no doubt that created the belief that sea bathing was the panacea for all the ills of the human body and its psyche. While it was this coastline that had provided for Blackpool in the first place, it was the railway that had created the path towards the modern town. Many places had come into existence or had been modified by the arrival of a railway line into their midst and the carriages which trundled along those lines were carrying whole populations into the future. From this time, a necessity to extend and develop Blackpool arose as it had to effectively accommodate these much larger numbers of visitors. But before the modern town could successfully come into existence, the coastline had to be secured, and by 1848 if Blackpool was to be considered a town, it would have to abide by the Health of Towns Act of that year, and before that, it had to have an elected administrative body to legislate within those boundaries, taking responsibilities, including the raising of funds to do what it had to do. From 1848 the existing Watch Committee made up of the gentlemen of the town and co-opted among them, and which controlled the area known as Blackpool in the parish of ‘Layton-with-Warbrick’ , would be expected to include a Board of Health with powers created in Parliament and endorsed and controlled by it.

The coast has always been here, though regularly modified throughout a geological and climatological timescale. Blackpool’s name, derived from its dark, peaty topography, had been planted for posterity on this coast by those who had given it that name in an undefined moment of history. But the first train has a definite date of arrival of the 5th June 1846. It had come all the way from Fleetwood, which already had a rail service of a few years’ standing due to the vision, enterprise and of course, contributory money, of Peter Hesketh Fleetwood, the large landowner of the north of the Fylde. The train brought the directors, shareholders and interested parties of the Preston and Wyre Railway Company. They arrived at the new north station, built by a Fleetwood contractor, and situated opposite the Talbot Hotel on the road built by Talbot Clifton, the large landowner on the south of the Fylde, in 1843. (He would of course, have actually ‘caused’ it to be built, since a team of skilled engineers and beer-swilling labourers would have actually done the work).

Large landowners might not have been very big in size that is but large in their ownership of land, of course.

When the train arrived, the district of Blackpool, on this north west coast of England and which wasn’t very big at all, was in expectant, celebratory mood, an energetic excitement that would be replicated with increasing values as the town progressed and found more good reasons to celebrate. The train should have arrived in March but there was a delay due to a collapsed culvert at Hoo Hill. So the decorations had to be kept in storage until the train was a reality. The hotels were bedecked with colour and flags and the processions of schoolchildren waving their own little flags welcomed in this first train to their home town, regarded far and wide as that favourite watering place of the north-west. There was a party afterwards thrown on the bowling green of the Talbot Hotel. I guess, this had to be in the days before bowling and bowling competitions had reached the zenith of their prestige and the green wasn’t then considered as hallowed as a churchyard.

Until the date that this first train had arrived, access to Blackpool had been by coach, latterly from Poulton, when the Preston to Fleetwood line had been opened and, prior to that from Preston, when there was no railway line at all. A coach could convey a handful of passengers, whereas a train could take thousands. A coach of four horses would travel about six miles an hour on average so the journey from Preston alone would have taken more than three hours. On arrival there would be a passenger load of sore bottoms and a queue for the toilet. A train all the way from Manchester would take less than two hours and you could be straight into the sea on arrival and, once these large numbers of folk began arriving, the town became busier, noisier, dirtier, and much more anarchic. As a consequence, much, much more needed to be done before the town could adequately cope.

This busy place, lacking sufficient infrastructure to deal with large numbers of people, was what the provisions of the 1848 Health of Towns Act were directed at by the middle of the 19th century. But if Blackpool was to keep its status as the successful watering place it had been for a long time– and now proving to be on a much larger scale – then, as well as complying with the specific requirements of the Act of Parliament, the sea, where it met the land, would have to be somehow controlled or contained in its aggression. The destructive storms that had mercilessly swept across the Fylde coast since time immemorial and often recorded since inhabited times, submerged both land and properties, and had always been a begrudgingly accepted hazard of life for the coastal dwellers. The storms of 1850 wreaked their own havoc, but after a very wet autumn of 1852 when much of the land remained under standing water for long periods (nationwide and worldwide, too), the storms of Christmas Day of that year, further convinced that handful of property owing men who would soon constitute the local Board of Health in Blackpool, that a serious, collective attempt should be made to bolster the coastline against such incursions and thus protect the property that was their home and their livelihood. Since these facts led ultimately to the creation of the first Improvement Bill and resulted in the development of the first Promenade, it could be argued that in the moment of that decision, the modern town of Blackpool was conceived.

If it hadn’t then I would probably be sat in a puddle writing this, about a mile inland.

Before the railways arrived, it was the popular, fashionable place for the more well-to-do, a place to convalesce or take in the health-giving properties of the sea air and these folk arrived by stage coach from Preston on a bumpy road. You could walk the high glacial clay cliffs of the north or take or a more leisurely stroll in the gentler and lower lying geography of the south, and the sands stretched for miles between and beyond the two. These walks had the space that the cities didn’t have. They were without the restrictions of the home streets of the cities and towns of these escapee urban or countryside dwellers who were denied a view of the sea that surrounded the island nation.

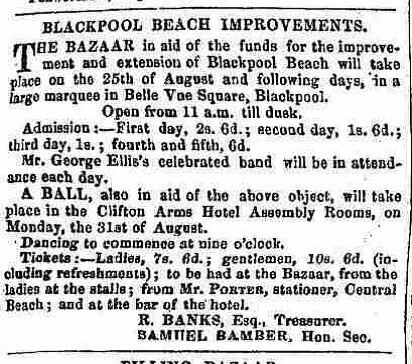

So the 1850’s saw much change in Blackpool. The town had to keep pace with the events that were creating its future status. Houses, quaintly called cottages, to accommodate the much greater influx of visitors were being built at a furious rate. Land was increasing in value as it function from spare land and farming to the more profitable usage of visitor accommodation changed. The land south of the Manchester Hotel with a sea frontage and the half way point between Blackpool and the separate entity of South Shore lost its old fashioned name of Tullet Hey and was renamed New Blackpool. Here, it provided prime land for building and an enticing name for the investors and developers. There was a street plan for 130 houses with the proviso that no house facing the sea front should be a shop. Blackpool was now a popular place in the eyes of many more people, accessible to all and now captured in the new kind of public imagination in songs like ‘Did You Ever Send Your Wife to Blackpool?’ The very male orientated sentiment of the song title, nevertheless reflected the attitude of the day and the fact that Blackpool was a definitive destination where you went for a good time and, perhaps, even could have a better time if the wife was away. Equally today the song title could be ‘Did You Ever Leave Your Husband Behind in Order to Have a Good Time in Blackpool?’ The plentiful hordes of today’s single sex female groups might vouch for that. I haven’t found the rest of the words and haven’t much of an urge to do so. Mr Porter may possibly have had the words in one of his items for sale. In the 1850’s he was a bookseller with premises on Central Beach, Blackpool and in Fleetwood and had published quite a comprehensive guide to Blackpool and its environs in 1857 at a ‘moderate’ price to those many visitors who would want to know more about the place they were visiting. The varied natural, geological and social history in his guide begins with St Paulinus baptising ‘thousands of the Fylde folk in the Ribble’, and proceeds to the era of Rossall’s Hotel.’, (now, after a couple of name changes, the Metropole). Maybe the prolifically proselytising and baptising bishop Paulinus did reach these shores and dip a few thousand folk on the Ribble and maybe, too, they reverted to paganism when he left. The baptising, in the moderated from of ritual dipping under the sea did happen later on, but it did not replicate the religious practice. It was more the belief of the moment in the ritually therapeutic value of sea-bathing, with or without your clothes on, away from the dirt and grime of the industrial landscapes, and in that sense, it became a much practical, rather than spiritually based application.

Before 1850, this bit of shoreline, in the memory of the living in their written records or the artist’s painting, was a steep grassy bank, and this grassy bank was a freedom to roll down for the young boys with a few days’ breathing space from their townscapes or later, from the claustrophobic and unhygienic living conditions of the heartlands of Lancashire, Cheshire and Yorkshire and beyond. The limekilns situated here and there on the foreshore, which supported the sporadic and continued building of properties along the coastline, didn’t bother any of these early holidaymakers, nor did they bother the birds which nested in the natural shrubberies in the high cliffs to the north.

As far as sea defences were concerned, what fence or walling that was placed between the sea and land from time to time before the 1850’s, had always been the responsibility of the owners of properties on the shoreline. Sometimes this fencing or walling was there only to define the property boundaries, and sometimes it was hoped that the stone walling, when it consisted of hefty, half-ton weight stones, and pinned and stuck together with iron rods and cement, would hold the sea at bay. This heavy defence could, and did, hold up admirably against a pleasant and gentle, summer zephyr, but not against an angry winter storm with or without a high tide to push furiously in front of it.

When these storm-envigourated seas washed ashore with fury, the doors of the exposed buildings had to be desperately protected with puddled clay, a material naturally provided in quantity in the geological timescale under the surface landscape as a glacial deposit. Sometimes the sea could get in to these buildings and sometimes it couldn’t with the clay packing providing as much desperate protection as a modern sandbag could afford in today’s flooded regions.

The owners of these sea front, private properties, were subject to quarrels, disputes and litigation regarding rights to the frontage. In 1850 Cuthbert Nickson had to publicly apologise with an insertion in a newspaper for assaulting a Mr Henry Truscott after the affair had been settled financially out of court. Henry Truscott doesn’t feature in the town and is possibly a non-resident visitor. The nature of the assault is not recorded but in 1852 Cuthbert and a few mates, all names connected with the property owners of Blackpool, were fined 5s (25p) and costs for drunkenness and, with a preferential for drinking lots of ale comes the need to thump your opponent to resolve an argument since a compromise is ever beyond the capability of someone who has John Barleycorn as a guiding angel.

It wasn’t always clear, however, as to who was responsible for the repair and maintenance to this bit and that bit of the coast, and who was not. The sea of course, loved all this human bickering and division, and was allowed to do just what it wanted, modifying the coastline to its own design and making deep and widespread incursions into the land, decorating it with sewage and flattened haystacks and bricks and rocks and the occasional boat and other, assorted debris while at the same time filling in the freshwater pools, which were a vital source of fresh water, with brine. Drinking seawater was considered healthy, but it can also send you mad, as the evidence of a castaway mariner in an open boat with no rainwater to collect would testify.

The Manchester Guardian of September 1850 has a good moan. It describes the popular watering place of Blackpool as in need of better drainage, lighting and bathing regulations. The Manchester people provided Blackpool with many of its customers and the newspaper, it seems, had taken it upon itself to stand up for them and complain about the poor state of the town. The newspaper emphasises the need for better lighting because at night the town was dark and dingy (and no doubt you couldn’t see what you were treading in or on). Also the town needed a much more reliable and efficient mail delivery. The blame upon this poor service was conveniently placed upon the only postman, who happened to be an old man ‘who is very slow in walk and apprehension and notorious for his blunderings’ and he took hours to deliver the post especially to the north of the town and district. The postman at this date was Esau Cater. The post would generally arrive at 11am and he would begin his round at 12.30pm, every day in Summer and three days a week in winter. However, as slow as the newspaper complains that the delivery is, it is an improvement on the case in Blackburn a few years earlier of a female ‘footpost’ being found dead (but alive, dead) drunk in a ditch with all her letters upon her.

Even today I always get a certificate of posting for my important mail, not just in case a female postie has enjoyed her ale too much, or all the postmen are aged, but because nothing is perfect.

CHEAP TRIPS ON THE RAILWAYS

The success of the railways all over the country in transporting large numbers of folk created the desire in many rich people to invest in them, (William Wordsworth initially didn’t like the railways because they destroyed his daffodils, but eventually came round to agreeing that they were really a good thing and invested a bob or two them I believe). A direct line to Blackpool from Preston was mooted from an early age. Landowners were approached about the sale of the land and how profitable it would be for them. Once the railways were up and rolling, such was the demand for excursion tickets from Yorkshire to Blackpool and the west coast that it caused disruption on the railway routes, on which the goods from Liverpool exacted a very large demand, and a headache for any transport manager especially as the rolling stock was limited in numbers.

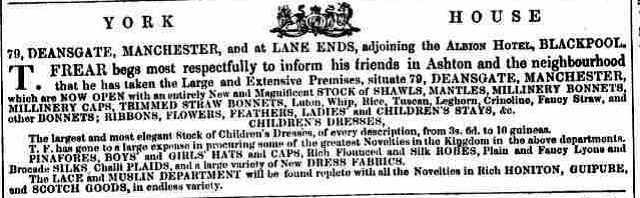

So, once the railway had arrived, Blackpool could be positively advertised in the press to bring in the investors as, ‘Blackpool is accessible from every part of Yorkshire and Lancashire by Railway, – its beach is unsurpassed for the firm, smooth and safe character of its sands, – the promenades along the coast afford views of the promontory of Furness, the mountain ranges of Lancashire, Cumberland and Westmoreland, the Isle of Man and the mountains of North Wales.’ Cheap tickets were provided for travel to the holiday resorts and this resulted in the large numbers of folk who took the opportunity to travel, largely previously denied them and they flocked off the trains at their destination stations.

After 1846, when visitor numbers increased, the fashionable image of Blackpool was modified by those plebeian commoners, whose rough manners and habits created an upwardly curved nose in the more well to do, but whose hard work, rough manners and miserable living and working conditions, had nevertheless nurtured and supported the Industrial Revolution and its subsequent wealth for the few privileged to enjoy. However, they could nevertheless be seen ‘disporting among the shallow waves’ and ‘far too happy to invite critical censure’. This working class of people who for ‘ten hours a day inhaled the oiled impregnated air of the factories’ arrived in the town in quantities, to disport in a sea they had never seen and to take the unique experience of a donkey ride vicariously as ladies and gentleman might ride horses. Or as the Era publication of the summer of 1853 reports with Liberal orientated opinion, in contrasting the ‘rough and ready’ travellers with those of the more materially privileged classes, ’No doubt, some pretty faces, which are allied with empty heads and cold hearts, sneer at the cheap trip and its excursionists, and some thoughtless and fastidious fools, perhaps begrudge the use of the railway for such travellers. No doubt the gentility of the watering place shudders and flies from the crowd who promiscuously unclothe and bathe from the beach on their arrival; and would faint at the horrid sight we once witnessed, of two ladies and a gentlemandescending together into the sea from a bathing machine. We grant that the manners of our cheap excursionists are occasionally rude and their habits exceptionable. But if the privileges of the silver fork are to destroy the charity of our hearts and the philosophy of our heads, may the next mouthful it gives us be a choker. If we can ourselves lounge in a well-padded seat of the “Express” train, and not rejoice at the sight of so many sons and daughters of toil enjoying a cheap trip, we deserve to run into a luggage train in the next tunnel we enter. In short, if we do not recognise as a prime benefit of the railways, that they facilitate communication betwixt members of the human family who must otherwise dwell apart, and so tend to refine all by inducing more general intercourse, it is certain that we are still as ignorant of the subject as the untutored artisan, who, we are wishing, would stay at home; and it would serve us right were we forced to do his work for our want of consideration and kindness’.

In the summer of 1850, there were so many visitors that the hotels could not accommodate those staying longer than a day, and the railway company found spaces for them in the railway carriages. Those unfortunate enough not to be provided with at least a railway carriage, would have to walk the restricted sea frontage or the beach all night, in the days before the piers were constructed which could have provided a little bit of privacy for either a bit of sleep or the acute desperation of rude things.

To others, these throngs provided the ‘revolting’ scenes witnessed on the beach by those with more inhibitions regarding body exposure. It was now only a distant memory for the old folk to recall the times when the women had an allotted time on the beach in which to change and bathe, and if a gentleman was either unfortunate enough or careless enough to break this prudent privacy rule, they would be fined a bottle of wine. Only gentleman drank wine. Everyone else drank beer. So, it seems that only gentlemen could be accused of being voyeuristic in watching bathing boobs and bottoms or, if not the full monty, then nevertheless eliciting interest even if the view consisted of voluminous bathing suit, lacking in compliment to the wearers who were temporarily deprived of their external, promotional attire. But this was in the old days before the beer swilling proletarian hordes arrived. By association then it was only a crime for a gentleman and not a lad from a metal foundry or some other common industry or employment. It was also now quaintly out of date to heed the advice on sea bathing, which was to ritually bathe three times and dip the head under the water three times. The bathing attendant did it for you if you were too timid or unsure of how to do it yourself. An incident in the late September of 1852 could be described equally as tragic or foolish. An un-named woman had allowed the bathing attendant to dip her child in the sea for the three traditional times but the struggling little toddler didn’t know what was happening to it and, screaming and writhing in fear which both the mother and the attendant ignored as an unreasonable objection by the child, it filled its tiny lungs with water and drowned. That’s of course if it hadn’t died of fright beforehand. The scene on the beach at the time must have been one of dire confusion, consternation mixed with horror, compassion and condemnation. That tradition for the triple dip was now for the more demure folk or those that didn’t take too easy to change. Times had advanced and had changed the rules to different things, and different people. Now it was, ‘just get in there’, and splash away the dire incarceration of factory life for the few moments of a single day! It was Blackpool offering its important contribution to progress. Bathing became dictated by the need not the rules. Women’s and men’s bathing machines gradually nudged themselves closer, to the interest of many or to the horror of others, and objectively described as ‘promiscuous’ bathing. Women could be seen dressed in flimsy, clinging, garments intimately giving away the detail of shape and form otherwise denied to the gaze of the world while the men, with whom they engaged in splashing fun could be dressed, if not in unflattering drawers, then in nothing at all, though perhaps those of more demure or retiring nature or the careless inevitability of the ithyphallic might keep the depth of the rolling waters above their waists when ridicule or horror might subvert the excitement of pride.

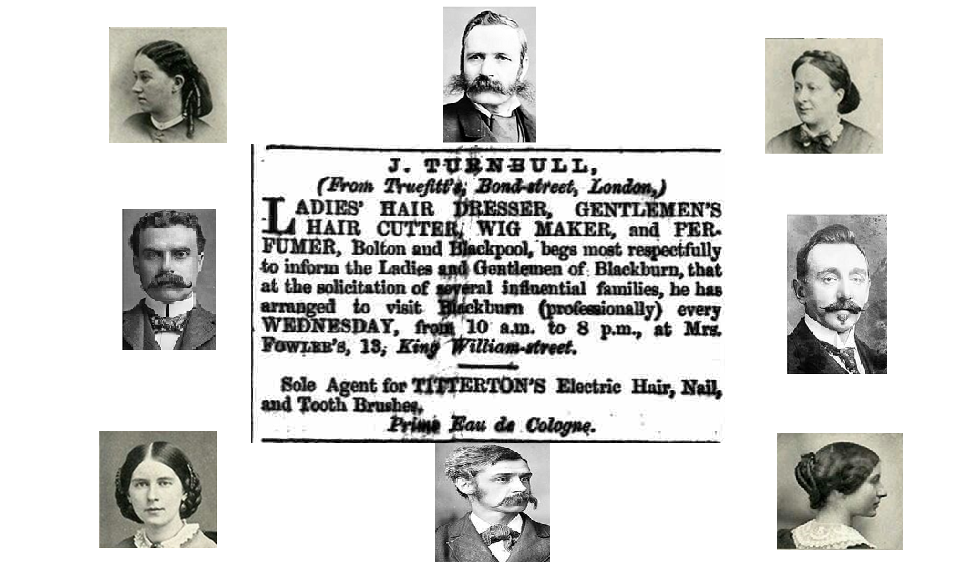

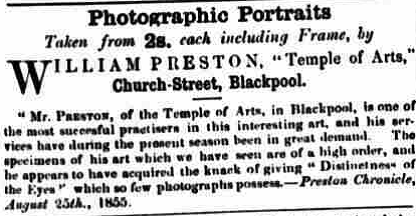

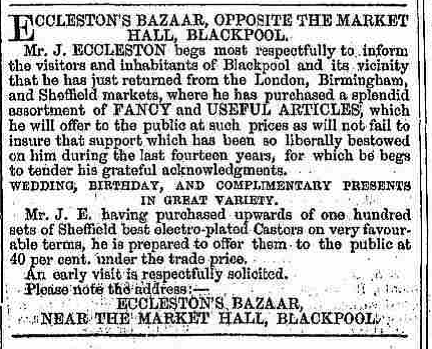

A visitor from Liverpool saw the town in 1856 in the following, contrasting way (which was after it had been cleaned up a little); ‘Blackpool presents every comfort, combined with cleanliness and economy, and it is not going too far to state that its private lodgings and hotels will bear comparison with the best-conducted in the kingdom. The stranger cannot be wrong if he stops at Rossall’s or Birch’s; the Lane Ends, Beach, Albion, Wellington, or Adelphi hotels; goes to Robinson’s, Duke’s, Brewers, or Craggs, besides others arranged in descending ratio to accord with the pocketology of the visitor. Pater-familias, anxious to get rid of his superfluous cash, may beat it occasionally – get blood horses from Noblet or Hayes – traps drawn by single or double ‘tits’ – canter on Jerusalem ponies –give fourpennies to hurdy-gurdyists, accordionists (the Liverpool street boy the best), black faced minstrels, harpists, violinists, banjoists, ad infinitum ad nauseam; or go to Viener’s or Eccleston’s bazaars – buy horses for Fred fit to run for the Bellinger – or Boomerang toys fit for the Black-ball ships; or if Ma looks uncommonly well, as she always does at the sea side, go to Preston’s Temple of Arts and have her portrait taken, the centre of the family group with Pa and Charles on the left and Dick and Polly on the right, with Frisk the active sea-side dog, on little Polly’s knee, if he will only be still – vain hope. It need only be added to set all the Dicky Sams on the qui vive, that a beach is a mile and a half long (thanks to the improvement committee) that Fleetwood, puny and significant as a port, is within an hour’s drive; that there are lots of opportunities for the Liverpool merchants to argue and bet bottles of champagne with the Manchester men on the town dues question; that the Lime Street folk (good souls) are sending some three or four trains a day, at about third class fares, with first class carriages, bring choice of 14 days to return in – and everything has been stated here to introduce into Blackpool more people during the next month of October from Liverpool than have been there for the last 50 years.’ Liverpool Echo 1856.

Note; a Dicky Sam is someone from Liverpool (had to look this up); nowadays a scouser. The Black Ball ships are variously shipping lines that operated between Liverpool and both USA and Australia. A 55 day voyage would get you to Australia with all the mail from the homeland sailing on the 5th of each month from Liverpool. The Company were proud of their ships, being well-equipped with comforts and amenities– including a cow (I guess so no-one would have to miss their cups of tea) and the fastest of the fleets. Weblinks in the end pages. Rossall’s is now the Metropole, Birch’s Clifton Arms, Mr Robinson’s Royal Hotel, Noblet probably John Noblett, livery and stable keeper of Albert Terrace. Hayes is probably John B Hayes from Lytham. The Temple of Arts built in 1847 (blue plaque) was occupied by John Eastham, photographer and up for auction in 1854 as a suitable premises for an inn or public building, before John Preston, photographer, acquired it. I assume the ‘double tits’ to be a pair of mares, though this could be a somewhat prejudicial assumption.

In September 1859 a former visitor to Blackpool who was experiencing Southport, but making reference to Blackpool, compares the towns in a somewhat verbose language;

…’And then, again, there are the hucksters and vendors of night caps and nutmeg graters, mussels and marbles, toys and tea cakes, toffy and tripe and Ormskirk gingerbread, with all the other little trifles that are always hawked about in every crowd, who seem to have got extra powers here … and they persecute visitors in such an impudent, graceless, merciless style of tyranny, that the sight of a policeman is a luxury that cannot be indulged in too often.’ This of course is a somewhat middle class view of a less affluent group of folk in the same society who mostly have to survive by their wits, and less by their privilege, whether they are an annoyance or not. The cheaper, private accommodation, affordable by the same social group is also criticised as being low grade with an unimaginative décor and service of a basic and naïve quality. Hot water at tuppence (2d. less than 1p) a head and sixpence (6d; a bit more than 2p) for an uncomfortable bed. The correspondent also complains of the donkey drivers who ‘impose upon their patrons and hammer their donkeys’ but do it in Southport more than their ‘Blackpool friends’ without regard to what anyone might think of them.

Or another, cheap trip train journey (Bury Times Saturday august 1859) describes the reality of the trip with a little bit of cynicism, in getting out of bed at 4am, dressing and packing up to make the journey to the railway station where you wait for an age to be packed into a dirty, ill-ventilated carriage in which you endure a four hour journey (Bury to Liverpool in this case) and then you hustle and bustle in a crowd of hundreds before you can get off the train, making sure you have all your packages and children with you. And then you have to get out of the station in a crowd of thousands keeping valuable members of the family together, (a bit like, today, leaving a football stadium after a match). And once out of the station, the crowds continue and fill the markets where you have to hustle and push to get close to the stall if something might take your interest. Or you would continue on with the crowds as they walked along the front being harassed every few steps to buy this, that or other trinket or petty morsel of food. You might queue for a bathing machine and even wear a costume as you dip under the health giving waters which have recently accepted some of the sewage that you and the same crowds in which you are mingled, have produced by drinking the beer and eating the pies on offer and the public toilets are as rare as a policeman. And buying the healthy sea water for drinking and taking it home in a bottle unaware of where the water had come from before being bottled in old gin bottles, watch the Punch and Judy from a distance because you can’t get near and hearing the strains of an organ grinder who probably hadn’t a wash for several weeks.

Blackpool was plebeian, almost philistine and uninteresting, to the imaginative or artistic mind, but who wants to contort their mind with the strictures of artistic appreciation, when the need to blast out from the mind for a day or two, the dirt and the dust and the noise of the oppressive working conditions that have been left behind for the day. There’s time now to observe the girls and the boys and time to get close, or very close or very, very close, or so close it becomes dramatically life–changing and the future is a different place to the one looked forward to on the crowded morning train. During WW1 the poet Wilfrid Owen didn’t like Blackpool and reluctantly visited the town from his hotel accommodation in Fleetwood. However the intellectual content of the RAMC stationed in the town included many poets and artists. He could have nipped in there for a pint and a discourse. The same human emotion was played out on the Blackpool Prom as in the further reaches of the poetic mind, delivered only in a different language.

And the correspondent continued to observe. The early morning rise for the journey meant a hurried breakfast and on the crowded station, the cruel parting of friends, final words perhaps prevented from reaching the ears by the loud hissing of steam from the engines and the noise of the crowds. And the crowded return carriage back home might be full of pleasant conversation, or of unselfconscious broad jokes which would make the ears of a sensitive person curl up. There might be an old lady in green bombardine with three boxes, two bottles, a warming pan and snuff box. An old man with a cold and a bad chest who had a kitten under his jumper to keep his chest warm. A young man with a clay pipe and who was self-consciously whistling a tune. A chap who was continuously telling boring stories and expecting everyone to laugh and react. And hours of this! Bless the inventor who made train journeys shorter! And a young girl, pretty in pink, but who had a dirty neck. You contrived to be in largely good humorous mood, whether you liked it or not since you had these people around you for several hours on the longer journies. Pastries might be shared while the carriage rocked and shook for the all the hours of the journey till home was reached, and the one day off in six for the worker had reached its conclusion.

Arriving at Blackpool, mid or late morning, you would walk on the sands, if you didn’t mind getting your shoes wet or dirty, and it could be an energetic exercise since there was so much of it and there was much to look at. You would be in the company of many strollers who were watching the many more active folk. The ladies in modest blue bathing dresses focussed the eyes as they demurely dipped themselves in the waves. Gentleman in drawers that perhaps didn’t adhere to a sense of the aesthetics of the human body who dived into the waves with less inhibitions than the women. And plenty of over-sized folk on donkeys which look underfed, and whose accelerator to produce movement or speed was the repeated thrashing of a stick by the driver, who would have to keep a supply of sticks after they continually snapped with the beatings, walking alongside. With their equine cousins the horses, ribs protruding, pulling carriages which looked none too safe, they did not have the benefit of the definitive rights of care that they possess today. That’s what it seemed to the outside observer, anyway, and it was a while before regulations would come in to the animal’s favour.

And there were children building castles in the sand, old people, with less energy, becoming redder in the face as the sun burnt them, or squinting out of eyes looking out to sea with poorly focussed glasses, wondering what was that on the horizon, a three-masted tall ship or a disgustingly wobbly bottom, boatmen competing and continually plying for custom, hawkers, trying to look the part, dressed to look good to reflect the quality and authenticity of their wares, but not making a very good job of it as the sceptical observer could note. And there were concertina and accordion players who ‘murder popular airs, and excel in impudence’, sentimental serenaders fuelled with the confidence of gin.

There were Afro-American singers who spoke with Irish accents and the black of their faces didn’t cover every inch. They were called negroes or worse, with impunity. Black was cute, they were those lesser beings who could be ridiculed and patronised and caricatured. There are still camp followers today who sycophantically trudge behind the invading armies of Hengist and Horsa unable to determine the quality of the colour black. And there were ostlers in striped jackets and always chewing straws waiting by the carriages. Generally the dress was very dour, if not black then brown or an unadventurous tweed, while the ladies might be a little more colourful. If not, they would be hidden beneath all-covering dark dresses and further covered with brightly coloured shawls and the sun kept further way by the little parasols that they held.

But it was noise and it was the freedom of a day from the necessary function of virtual life as a machine part for the day tripper from the industrial heartlands of the North West and beyond, if perhaps a little of inconvenience for those who could afford to patronise the posher hotels but nevertheless take the advantage of the cheap tickets on offer.

And there were the bathing machines. The sea was an unknown quantity to the first time dipper. Undressing inside a machine was like the apprehension of a climbing roller coaster, waiting for the g-force of the drop. Once contortedly in costume, or for the men at least, occasionally without anything at all before bye-laws were brought in to ensure all bathing machines provided their male customers with suitable ‘drawers’. For those fortunate enough to have a bath facility at home, it was still a rude wakening to be immersed in the vast quantities of water of a seemingly endless sea, unlike the few gallons of a bath-tub. The first time for you in public. The bathing machine attendant would dip you the three standard times under the water and then you would, theoretically anyway, feel much more healthy, and then have the even more awkward and cramped effort of getting dry and dressed. There were bathing disasters and tragedies as well as horses shying and running away with the bathing machine. And there many drowning tragedies over the years too. And it wasn’t just the bodies of unfortunate and often unknown mariners that were often washed ashore.

The correspondent who provided much of the information above was staying at the Wellington Hotel, abode of the Bickerstaffe’s though he may not have known that at the time, and was one of the very few correspondents on any line of work or modern film that actually went to the toilet, after which he had tea and gazed out of the open window of his room across the evening beach, where today’s central pier would be constructed in less than a decade’s time, (but called the south pier then) and where the throngs of visitors were eking out every last moment of the limited few hours of their day’s holiday escape.

After tea, this correspondent and his travelling companion then decided to walk through the town, to the extent that it was a town. The buildings didn’t represent a design to excite the imagination or enquire after the architect. While the hotels showed some style they were a little overdone in decoration, the smaller, private cottages and houses were mostly the same old functional stuff with little imagination about their construction. St John’s Church of 1821, and its further improvements, was nevertheless an uninspiring brick building at least until the 1870’s re-build and, in 1859 only the new, Pugin-built Catholic Church in the town came in for his praise. The market house was a ‘low, dark and insignificant building’ as was the fish market. He was pleasantly surprised to find Viener’s bazaar, recently located to new premises on Talbot Road. Here you could get everything that was ‘neat, elegant, useful and ornamental’, from books, bags, work boxes, jewellery, Jew’s harps, bracelets, desks, drums and more. Back at the hotel at the end of the evening they called for the bootjack, chambermaid, slippers, candles and, with a swig of brandy, retired for the evening, and were soon ‘soundly asleep betwixt the snowy sheets.’ Perhaps they shared the same bed but were only ever interested in sleep. Beds were shared as was the norm.

The morning was a rush as they were up late as the sea air, the exercise and the brandy had been conducive to a good sleep and the breakfast of tea, coffee, eggs, ham, beef and bread was quickly eaten after which they jumped into a rackety carriage to take them to the railway station.

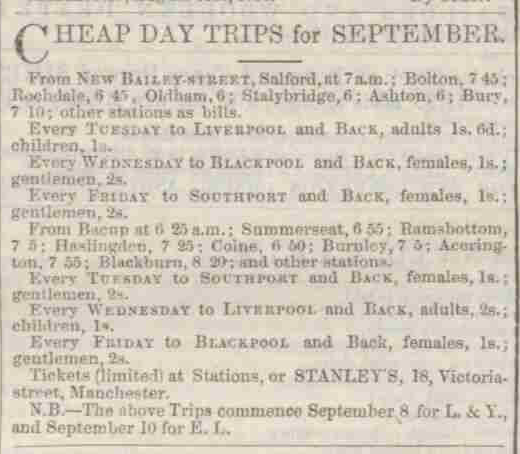

Cheap Ticket rides 1858

By November 1859 a new express train would run between Manchester and Blackpool and Manchester and Lytham and would take one and a half hours.

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, the private company operating in the North West and Yorkshire, advertised its cheap rates in the newspapers to any of the popular holiday destinations on the line run by the company, ‘members of institutions, mill hands, conductors of Sunday-schools, and others will be liberally treated for day excursions.’

These day trippers arrived in great numbers often as those organised work parties, charities or societies. Each group could number thousands in their parties especially on a weekend, Sunday being particularly the busiest on occasion.

But the trips didn’t always pass by without incident to dent the potential enjoyment. There were accidents, deaths, delays and court cases and the insurance companies get in on the act as part of their business. For a single journey an insurance of £1,000 could be taken out at 3d (bit more than 1p), for first class, 2d for £500 in second class and 1d for £200 in third class.

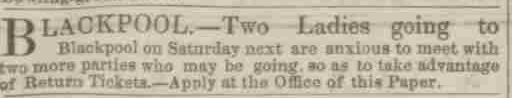

And to take advantage of the cheap, block tickets, individuals or small numbers of friends themselves advertised in the papers to any group that had spare tickets.

This paper being the Sheffield Daily Telegraph of Wednesday June 16th 1858. Perhaps they got their tickets or perhaps not, but the following week three young ladies were advertising again in the same paper.

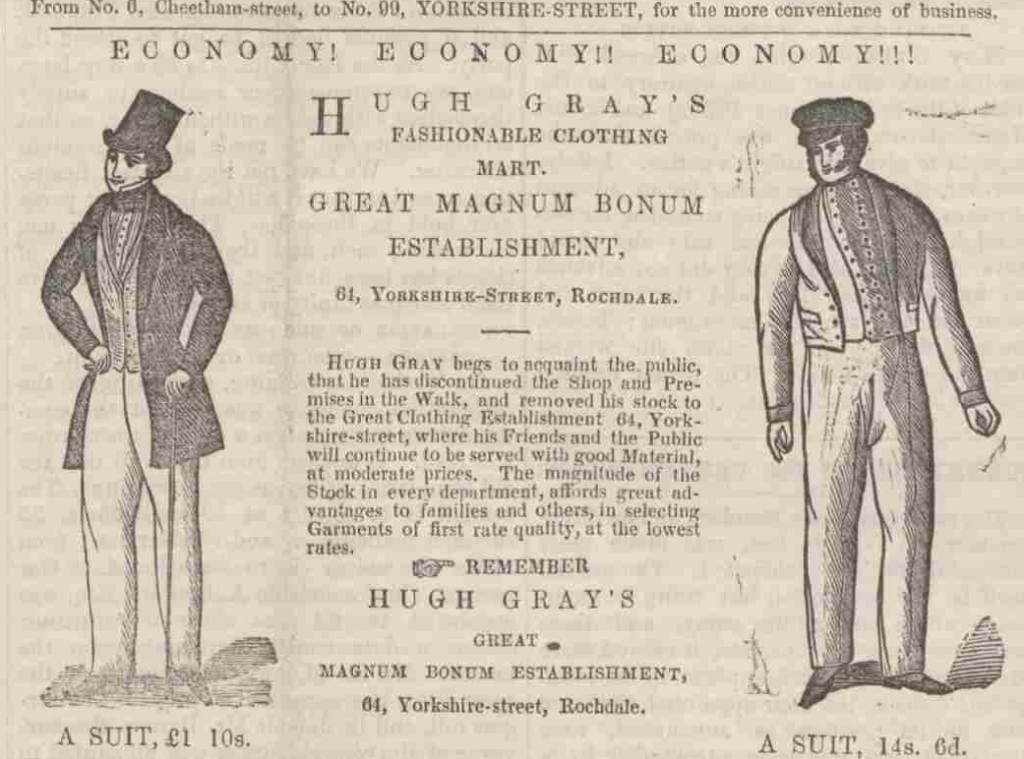

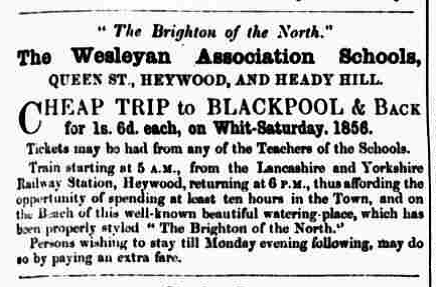

An agent in Heywood in the summer of 1857 had advertised a trip to Blackpool at 2s (10p) for men and 1s (5p) for ladies. However there was great confusion on the platform as the stock of tickets, especially the 1s ones ran out and then there was further confusion as the scheduled train rushed through the station without stopping, leaving a packed station of hopeful travellers waiting another three hours for another train to Blackpool. You had to go to the station to get a ticket. It wold be another hundred years and more before one cold be ordered by phone via the Internet. The railway officials gave the excuse that not enough tickets had arrived at the station and they were also short of carriages since the day coincided with Doncaster races and they were needed for that. By late morning however a train of 30 carriages arrived and actually stopped and took the passengers for a much shortened day out at that favourite watering place, the Brighton of the North. A bit of a blip. Nothing can forever run smoothly. Today’s ubiquitous ‘f’ word of universal meaning of contempt, popularised I think by American troops of WW2, might well have been popularised nearly a century earlier on that day had it already had a popular existence. In the same summer season the hundred mile return trip from Manchester was conducted without incident at the same price and thousands of 1s ticket holders enjoyed a full day out.

It wasn’t the only time that there wasn’t the capacity to take the number of passengers that wanted a day out in Blackpool. Tickets had to be refused to some of the 4,000 people who were packed onto the platform of the Trinity Station in Bolton because there were not enough carriages to accommodate them all. Ticket touts flourished before the greater price that you could get for a ticket outweighed the desire to go to Blackpool for a day. You could wait for another cheap deal another day and have plenty of spare cash to spend at the seaside destination. The train with the lucky, or out-of-pocket passengers on board, had set off early morning and had returned by 11.30 with no doubt a lot of tired passengers in its carriages. £1,000 was taken in ticket sales on that day.

Some people however, did not get home at all. In June of 1857 a man was travelling back to Manchester and put his head out of the window and sadly, catching it against a bridge was killed. ‘His brains were dashed out and he was killed instantaneously’.

In June of the same year a school party of 700 ‘excursionists’, as the paper describes them, travelled to Blackpool for a day out. They were from the Hope Chapel School in Salford and presumably supervised for most of the time. On the way back however, a few young lads clambered up onto the canvas roof of the carriage they were travelling in, despite the warnings of other passengers. They were having a bit of a lark and travelled in that manner out of Preston. One of the lads became distracted and waved his handkerchief to some people on a bridge who were egging the lads on. For some reason he didn’t think to duck before a bridge, and his head collided with the structure collapsing him into the arms of the lad next to him and he was seriously injured, losing ‘a good deal of blood and probably two or three teaspoons of cerebral matter.’ He was not expected to live.

30 year old John Cassell was also killed at the end of a day out by train. He was going to back to North Dean (which I guess is the Keighley one) and the train had stopped at Black Lane Station between Bolton and Bury. He was a man of stable character it seemed, and he was in the company of friends one of whom was his girlfriend (‘a young woman to whom he was particularly attached’) and he was well liked. He had stepped out of the carriage at the station to get some water but on his way back onto the carriage he slipped and fell between the platform and the train. Presumably the train could not be stopped as all the carriages passed over him as the train was moving. When his body was retrieved by some platelayers ‘his head was frightfully mutilated, and his arms almost severed from his body. Death was instantaneous.’

And of the passengers it was then and it is now, not unusual for at least one of them to be drunk on one journey or other. On the way back from Blackpool to Mytholmroyd after a day trip a Mr John Suthers, described as a reedmaker and in a drunken state began to abuse a young female passenger in the same carriage but he had to deal with a Mr Samuel Whitehead who was a sack agent for a railway company and who jumped up to her defence though was greeted with a thump in the face by Suthers. There would have been quite a kerfuffle in the carriage before things calmed down and the assailant was later arrested and fined both for the assault and for being drunk. He had to pay £2 and £1 5s 6d (£1 30p) costs for the assault and 30s (£1 50) to pay for the insobriety.

Also in July of 1859 James McCullum was on his way back to Belfast from Manchester and, with much of the hard stuff in him, got in a Blackpool carriage instead of a Fleetwood one for the steamer back home. He became aggressive when asked to leave and his mate, William Neill, a Manchester man, got in on the act and aggressively obstructed the guards when they had asked him to leave. They were both fined 20s (£1) and the magistrate warned that drunkenness would not be tolerated on the railways. July was not a good month for railway workers as a porter was kicked in the face by a man recorded only as Eccles on the station at Accrington on the cheap excursion night train back from Blackpool to Burnley. He admitted the charge straightaway and was fined 10s (50p) and costs.

And there were fare dodgers, sometimes hiding behind the contrived innocence of ignorance. In the late season of 1854 George Hill, a wool stapler of Luddenfoot took his son to Blackpool in June of that year and, as his son was under three years of age he did not need to buy a ticket for him. He had left his son at Blackpool for some weeks, I guess with relatives, unless of course he had already packed off his wife to Blackpool, and in the meantime his son had passed his third birthday so when he was collected by his father, he should have had a ticket. Inspector and railway police were present on the trains and one of them had collared George Hill for not having a ticket for his son. He claimed he had enquired about whether a ticket was needed or not and was told that it was not. This does happen all the time. One person says one thing, you think it’s genuinely right but find out that it’s genuinely wrong, because another person says so. George White resolved to appeal his case but whether he did so or not is not known but in the meantime he was fined £2 with 14s 6d (72½p) costs.

In mid June of 1857 there was an unusual reason for an influx of visitors to Blackpool in the form of a comet that was about to hit the earth and the people of Preston had become particularly alarmed. Fire proof safes had been in large demand as the ‘end’ might have been nigh, a cataclysm which could be survived by the privileged and their valuables retrieved if they were some of the lucky ones. Similar I suppose to the building of private underground bunkers in the event of a nuclear war reflected the fear of some people during the Cold War of the 1950’s. People immigrated to Blackpool in panic in the belief that the comet, if it should strike the earth would not have as big an effect there for some reason. Blackpool was already then a place of refuge from the ills of life, or somewhere you would want to send your partner if you wanted to be rid of them for a few days and it would not necessarily be just away from the horrors of war ‘far away from the Zeppelins’, of WW1 or the harshness of living and working conditions. It was the mother who was always there to whom you would rush in a time of need, clinging to her skirt with your thumb in your mouth as a comforter. Businesses were sold up at a loss in order to get away from the approaching Armageddon. One ‘gentleman’ a pig dealer, sold all his stock of pigs at the market in order to retreat from the approaching comet and Blackpool provided that maternally endearing escape from it. He didn’t make any friends on the pig market as there were so many pigs it caused a drop in the price of the animals. Good for the buyer who didn’t believe the comet would strike Preston and bad for the sellers whether they believed it would strike or not. Booksellers were the ones to profit besides those who bought cheap pigs. A 1d (one penny, and less than 1p) copy of the description of the comet made a good profit. Many people in Blackburn stayed up all night watching the skies and in Darwen many people went up to the coal pit at Blacksnape for, if the comet should fall, they could nip down the coal shafts for safety. Somebody in Swansea was flying a kite with a lantern attached to it and caused a panic since many folk thought it was the comet. Perhaps just a bit of Welsh humour, maybe. An Irishman being burnt out of his house in Scotland and probably not for the first time and thoroughly sick of the Irish land laws even persisting in Scotland, merely stated that ’so what?’ If the comet is going to strike then he was going to be burnt to a cinder anyway. A little bit of stoical Irish humour.

Though the Oddfellows had their Wellington Lodge in Blackpool, in Ethan Carter’s Adelphi Hotel, there were those from out of town who would have come by train. The ladies get in cheaper again.

But these swarms of cheap ticket riders vacating the inland towns and mixing with the first and second class passengers and enduring their contempt, for a day out at the seaside were a cause of concern for the economies of the towns they were deserting. At a cost of 3s (15p) for the day out including the fare, (could be as little as half a crown; 2s 6d or 25p in the 1850’s) and the stationmaster of Blackpool North claiming that on an August Saturday in 1851, 12,000 people visited the town on the cheap excursions, a single town would lose out an estimated £1800 of expenditure, despite the fact that these people would bring their own provisions with them, spent in the town they were vacating for the day. But the canny shopkeeper would fight back. The Duke of York Inn on Friargate in Preston assured the cheap day trippers that it would be ‘very much to their advantage to purchase their wines and spirits’ at the Inn before leaving. Sensible competition. By 1853 proposals and share applications for a direct route from Preston to Blackpool through the increasingly popular watering places of Lytham and South Shore were advertised.

Beginning of the season costs to Blackpool from Wakefield in April 1859. A 28 day return ticket was now available. In June of the same year a special train from Manchester to Blackpool via Preston was advertised at a cost of 1s 2d (8p). It would set off at 9.30am and return at 7.05pm, though no luggage was allowed.

And everyone came. Workers’ annual trips and religious groups and conferences, and the poor were given trips by charitable organisations and in 1854 this included the poor people from Preston, one of whom was 103 years old and the other 99, both from the workhouse and they probably didn’t take off their clothes and rush headlong into the inviting sea, revealing their wrinkly bottoms. The Oddfellows were also responsible for bringing parties to Blackpool. In 1858 in connection with the Widows and Orphans Fund, such a trip was brought to the town. Even today in an age of public social security, there is still a great reliance on the magnanimity and the generosity of volunteers to keep the sentiment of charity alive. Hospitals and heritage rely heavily upon the generosity and the time of the volunteers.

The trips of course, were cheap and because they were cheap, (1s; 5p day return for a child under 15 and the same price for adults with an offer) the railway companies packed as many fare paying passengers as possible into the carriages. Occasionally a well-wishing employer would offer cheap trips to the ladies to the ‘famous sea bathing place of Blackpool’ but, if the men wanted to go too, then they were very welcome but had to pay a little extra for the privilege. It was never a smooth ride, bumping and clanging and swaying and starting and stopping in carriages that could be open to the elements and devoid of seating, ‘not even a strand of straw to sit upon’ bemoaned one unfortunate traveller.

The carriages, closed or open contained a variety of folk mostly in escape from their working and living conditions. But you can’t wear your work clothes for a day’s holiday. You have to get somewhere near your Sunday best and this would be old or borrowed clothes worn with a certain amount of pride, in a solecism of fashion statement and mixed with the discomfort of strangeness. Some, in their dirt and grime have been described as more like the Australian diggers from Bendigo or Ballarat, towns also known for their frontier lawlessness, so it was a further dig at these innocent travellers who just wanted the privilege of a day out to behave for 24 hours like human beings rather than an impersonal extension of a machine process for the greater percentage of their daily lives. And the language was crude, not in its content but in its projection and expression in the ears of those rich enough to be able afford the time and cost of more regular travel. And this mix of people which included families and groups of single sexes fine-tuned with an excitement that would dispel itself in the waves and the sea air on foot or on donkey back (the Jerusalem ponies as they have been called). Or listening to the band that was projected to play on the promenade by the late 1850’s in the contentment of family relationship or the excitement of new found friends in increasing closeness of bodily contact.

And ‘an enemy of cheap travel’ complained that despite pre-booking accommodation, he was nevertheless obliged to spend the night with his wife and family on the stone kitchen floor. Chairs, sofas, floors and even bathing machines, were used as emergency accommodation. The beds themselves were occupied both day and night, in the style of Aldous Huxley’s Wigan Pier, and was not particularly unusual. When the morning came and the occupant got up, those that had been walking the streets all night with distressed and crying children, might have the luxury of a bed to rest in. It would not be to consider the accommodation owners human if they didn’t charge double for the occupancy of the beds, since charity and profit aren’t themselves compatible bedfellows, but perhaps the owners were so inundated with the demand for beds that, if they could make a bob or two out of it in the efforts of their provision, then c’est la vie.

These cheap excursions must have been profitable for the railway companies, or perhaps they were underwritten by the high fares of normal travel, so much so that a group of residents in the Fylde got together to subscribe to a number of coaches to travel the popular out of town routes which would undercut the rail fares. The railway was in danger of taking away the monopoly of the age-old method of coach travel which was fighting back in much the same way as air travel was held under suspicion as a rival when its popularity began to chew into rail and coach profits in the next century. The popularity of air travel was promoted by that friend of both Blackpool and Amy Johnson, William Courtenay, at one time in a plane called appropriately, ‘Blackpool’. But that was for the future. In this era of the mid 19th century, daring and adventurous folk, including many women, who apart from an occasional titillation, kept their clothes on, were confined to balloons, and then airships, demonstrated at Blackpool by Stanley Spencer before the heavier than air machines got off the ground in just over half a century’s time.

The excursionists nevertheless had to get home, and occasionally this could be fraught with danger. In late August of 1855 an excursion train of fifty carriages, having set off at 6pm from Blackpool, was stranded through running out of water in the Summit tunnel at 2am. It was pitch black even if they hadn’t been in the tunnel, and many of the passengers would have been asleep through sheer exhaustion and they would have been startled from any pleasant dreams by a goods train running in to the back of them. Two of the rear carriages were severely shattered and passengers were thrown across the tracks, one of whom suffered a broken hip but fortunately there were no more serious injuries. The Summit tunnel was on the line from Leeds to Manchester and through which the thousands of day trippers from Yorkshire would travel for their day out in Blackpool. It is one of the oldest railway tunnels in the world (Wiki). Of course, at that time, it would have been one of the youngest.

Sadly a cheap day out at Blackpool did not favour everybody. In June of 1857 a young girl, Mary Atkinson and only 23 years of age, hired a bathing machine off Mr John Crookall. He was dipping her in the sea when she began to faint, so he took her into the machine where, it was diagnosed later, she died there due to a weak heart. To be dipped under water might have been a strange and unique experience for Mary, which might have not been without apprehension. Grown men (if they are to be erroneously considered the criterion of stability and toughness) had expressed the nervousness of undergoing such a ritual. The well to do might have had a bath facility at home, the poor didn’t, and it might have been too much of an anxiety for her. Facing the might of the uncompromising ocean is a little different to stepping into the limited dimensions of a bath tub or washing at an outside stand pump.

In 1858, poor old (or young) Sarah Hewitt of Purston Jaglin, (a new name to me; I had to look it up) near Featherstone, should never have thought of going to Blackpool for the day for she was struck by lightning and killed instantly as she was getting ready. She was at home and, since it had begun raining heavily, she went to get her umbrella when suddenly there was a loud clap of thunder and a blinding flash of light. A brick was blown out of the chimney and the clock on the chimney breast was broken by it. Sarah was found on the ladder to the ‘chamber’ (not sure whether this was up or down to the chamber), and one of her boots was ripped open. With difficulty, the landlord and his wife extricated her from the ladder but she had died before she could be offered any medical assistance.

Also in 1858 Martha Swithenbank had had a good day out in the town but when she got back on the train to return to Bradford, she felt faint and became unconscious and remained like that until she had reached her destination where she was found to be dead at the station. Perhaps it was the excitement of Blackpool or maybe the depression of the necessity of returning to the mundane nature of day to day life.

Blackpool was also a place to come to for the health, but it didn’t help everybody. In August of 1858 Mrs Elizabeth Smalley, a grocer’s wife from Accrington came to stay in the town with her sisters. Her illness must have been quite severe and one that could not remedied with the medicine of the day. After several weeks of hoping to get better, she was found on her bed with her silk handkerchief tied loosely round her neck and attached to the bedpost. Even though Dr Cocker attended along with chemist Mr Moore, cause of death could not be determined as suicide, but rather a disease of the heart. Perhaps the doctors were being kind and compassionate.

For those travellers who could afford the first or, perhaps, second class carriages, there would be no cold floors to sleep on at night, but comfortable accommodation and fare provided by those innkeepers who were prepared to please for a price. There would be a regulated dip in the sea rather than a crude surge for the waves revealing legs or garters. They could have their photograph taken, if the photographer wasn’t drunk of course. In 1858 Richard Holt, a photographic portrait taker of South Beach, was found asleep in Preston New Road and when woken up by a constable he became abusive and assaulted the constable. He was fined 5s (25p). He was perhaps unlucky that the only policeman in the town happened to be passing at the time.

And death is the same for all folk, whether you are first, second, or third class or even have to walk all the way. The mayor of Oldham, Mr George Barlow, a long serving and popular chap of his home town for over 30 years, had returned from Blackpool in the September of 1859 and immediately began to feel unwell and, after a short illness, died at the young age of 54. He was expecting to retire from public life at the end of his mayoralty.

It was customary to go to Blackpool for the health giving properties of the air and convalescence and this was considered an important consideration over and above the pleasures of donkey riding, drinking and meeting people essentially as part of being in the town. However if you want to convalesce it is dangerous to bring with you your seventeen year old ward, a niece of your wife’s who has been brought up as a part of the family. Up pops a ‘canny Scotsman’ to sweep the young girl off her feet. Her parents were so concerned that they sent the girl back to Huddersfield their home town but the Scotsman followed her and found her, and they ran off together before the parents returned. The parents got her back, no doubt with the mindset of the day on their side but again the Scotsman, with blind passion or ineluctable infatuation followed. The story ends there, at least in the report of the story. Whether they got together or not is not known. My grandmother was swept off her feet in Blackpool by a Scotsman. Unlike the man above, his name is known but little else is revealed about him. She had come to Blackpool with her husband during WW1 and her husband left for France and never returned and is now just a name on a memorial. Broken hearted she was lured into a relationship to fill the empty space in her life. And the Scotsman filled it for a short while. But he was a bit of a bugger who eventually left for good, leaving my grandmother to nurse my mother, whom they had created together. Neither my mother nor her two half-sisters knew who their fathers were. My mother was told that her father was the chap who let the water into the circus for the seals at the aqua show at the end. But he wasn’t. He was he chap who buggered off back to Scotland never to be seen again. His father had allegedly worked on the construction of the Tower after the completion of the Forth Bridge in 1891, and the Tower construction was started shortly afterwards.

Where the town wasn’t the sole prerogative of the cheap ticket excursionists, there was provision for those of means. In 1858 the brother of Major General Havelock, had come to the town for his health and to visit by day trip from the cotton manufacturing town of Preston. General Havelock was that most revered man, and a typical Victorian gentleman of styled hair and generous, fluffy-white sideburns of Lucknow fame who had taken the city from the Indian rebels, too late to have prevented a massacre of the inhabitants. It was a time at which the church collection boxes of St John’s Church tinkled with the sound of coins for the relief of those suffering in those Indian mutinies (presumably only those Brits and allies who suffered). Once General Havelock had gained access to the city it had itself become besieged by a larger force of the enemy (who were actually the people who lived there and whose heritage they wanted to retrieve) and then he died of dysentery under the severe conditions of siege, before the city could be relieved. He was a good soldier by all accounts and had a charitable, ‘Christian’ heart which put him in good stead in the conservative religion of his homeland. But it was his brother who was visiting the town, not he, though no doubt riding high on his own brother’s fame. Eventually a statue of the general was built in Trafalgar Square, such was the rush of emotion towards him. So it was a good time to be the brother of a hero.

My G5 grandfather was Prussian, a quarter gunner in the British navy, and he was working in Carlisle as a weaver at the time of Waterloo. It would probably have been good to have been Prussian at the time. It was the Prussians who had dug Wellington out of a hole at Waterloo arriving, like the US cavalry in a cowboy film, in the nick of time.

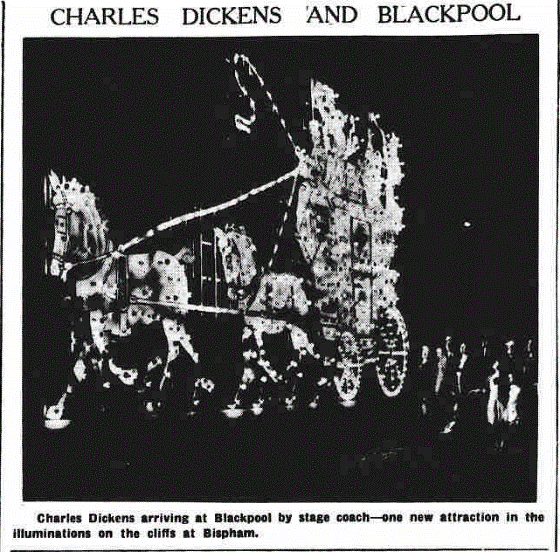

So in Blackpool, there were posh hotels for posh people as much as there were floors and multi-occupancy beds for the non-posh people. In September of the same year, Rossall’s Hotel, quite a posh hotel, which is now the Metropole, accommodated Miss Burdett Coutts and her party, which was probably quite a numerous one consisting of friends and attendants for she was the richest woman in Britain. I guess she enjoyed her stay for she remained for quite a while and, on leaving, she donated £10 to be divided equally between the Blackpool Infant School and the Blackpool Provident Society. Using the online inflation calculator, £10 would be equivalent to a spending power of about £1,246 today. Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts was a philanthropic woman of the Church and in society in general and a friend of Charles Dickens and she conducted much charitable work for the poor and needy in London and under her presidency the NSPCC was founded. (thanks, Wiki). She was in the company of Lord and Lady Sinclair. Thanks to Wiki again, James Sinclair, 14th Earl of Caithness and seemingly Liberal in politics, was also an accomplished inventor. Though concerned with creating and modifying machines using steam with an eye to the efficiency of their future use, he also diversified into inventing a false leg, though presumably not steam driven. While Blackpool was a centre for the assessment of false eyes during WW1 there were many men in need of false legs at the hospitals and large Convalescent Camp. When I worked at Norcross for the then DHSS, a first ‘proper’ job after a few years of chopping and changing, I was on the War Pensions awards and there were men from WW1 who were still receiving their pensions after fifty years of being alive with none, or perhaps, luckily a single leg. Perhaps James Sinclair had seen first-hand the injured men returning from the Crimea. An ancestor of mine, a cousin I think, of my great grandfather lost a leg in the Crimea. He was naval man from Plymouth. Even with one leg though he couldn’t keep away from the sea and got a job transferring personnel by rowing boat from the shore to their ships moored in the Hamaoze. Perhaps he had a false leg and perhaps it had something to do James Sinclair’s inventiveness.

It wasn’t only the day trippers that made the journey to the coast. Birds, possessed with the freedom of flight, and din’t need a train ticket, to the envy of the human being below them. Insects, too. There was a swarm of sand flies one year in 1968 while I was working on the deckchairs after school had finished officially for the last time. They were quite a nuisance and deckchair sales were reduced in number that day. Fortunately however they were not locusts as in late in the year of 1857 when three locusts were found in the town. Notorious for their swarms which blacken the skies in their densities in various parts of the World, these three must have become detached from the trillions of their friends and one, if correctly identified, at last found its way in to the collector’s jar of confectioner, Mr Brown of West Street in the town. It lived for a couple of weeks and then laid eggs, which was perhaps, the evidence might suggest, the original intentions of lady locust’s decision to come to Blackpool with a man friend for the weekend.

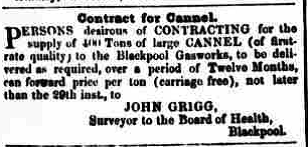

In 1858 the railway companies experimented on the Manchester to Blackpool line by using coal instead of coke as the fuel. The cost per ton was less than half the price (5s 3d – 26p – as opposed to 11s 6d -57p- for coke) and the consumption was less, making the total cost of the 48 mile trip only 10s (50p). It seems that it was a successful experiment as far as running costs were concerned. However, the cost of converting existing engines would be prohibitive. The Lancashire test had however, demonstrated an affordable and effective conversion. The problem with the dirtiness of smoke though had not been addressed, and the towns and stations and countryside and passengers had to put up with it. A Parliamentary Bill requiring all new engines to burn the smoke that they use thus preventing the universal distribution of dirty smoke nuisance to places where it shouldn’t be allowed, and liability resting upon the shareholders and owners, had yet to be tested in law. Some towns were threatening to sue the railways. By 1850 in Liverpool there were fines imposed on factory owners and a steam boat owner for not dealing with smoke effectively. The smoke and grime of the cities was in stark contrast to the fresh breezes of the non-industrial, coastal watering places and emphasised their status and increased their charm.

Oh! For the fresh breezes of Blackpool!

STORMS

So by 1850, it becomes evident that there have been four main elements which were responsible for the development of Blackpool and the creation of the town as it is today. The first, probably in a correct chronological order, is its presence next to the sea, the second is the continuity of the severe storms that visited the coast and carried the sea some distance inland to endanger life and property, the third is the arrival of the railways after 1846 when the town found it had to cater for vastly larger numbers of people than it had been used to and the fourth is the Health Act of 1848 which was responsible for Blackpool creating its first definitive boundaries and a group of formally elected administrators, which ultimately became today’s town Council.

The Storm of 1850

The storm of 7th October 1850 was described as a hurricane ‘the likes of which had not been witnessed since 1839’, which was only 11 years since, and which probably implies a consistent occurrence of lesser, violent marine visitations to the land, and were observed by many folk, inhabitants and visitors alike, though more of a spectacle to the visitors who would not have been used to such dramatic events, at least those that involved the sea too. At this earlier date the whole of the northwest suffered great damage, but the area of the coastal Fylde was particularly susceptible to storm damage. Cottages were stripped of their thatched roofs, windows were blown out of the more substantial houses, slates blown off these roofs with violence and chimney stacks tumbled. Mr Dickson’s hotel lost many of the slates from its west facing roof and Mr Nickson’s Albion a little further south had most of its windows blown out. Many vessels were torn from their moorings in the River Ribble and scattered to Freckleton and Lytham. Even the three ton Ribble buoy was torn from its fixed point and carried as far as Red Bank in Bispham. The Fylde coast shore was littered with the spilled and high value cargo of wrecked shipping which included chests of tea, bales of cotton and other cloths and even, unusually perhaps, elephants’ teeth. It’s known that some of the crews were saved and others lost their lives. Some of the cargos bound for as far away as India were recovered by customs officers, others not, and collected by anybody who could get at them first, and still more cargo was ruined.

During twelve hours of severe wind, thunder, rain and lightning, that ‘electric fluid’ which could kill livestock and did so with one of Mr Thomas Moore’s cows of Blowing’ Sands (sadly Thomas Moore wasn’t one of those successful businessmen who by luck, skill or clever deception made their money since, by 1858 he had become bankrupt.) The storm shook and rocked houses causing the occupants to ‘rise out of their beds’ in case their houses fell in upon them. Chimneys came down and slates were ripped off the roofs.

A vessel, the Portia, on its way from Liverpool to Troon and from there, with the expectations of reaching the Mediterranean with its cargo, found its destiny unexpectedly to be the beach by the Gynn where its crew were saved by those on the shore at first firing a line from a rocket to the wreck. A rocket line had recently been invented by a Mr Carte and a station for firing it constructed and paid for by Benjamn Heywood opposite his mansion where the trials of 1845 had been witnessed by a large crowd. The East coast already had, it is reported, fourteen of these stations, and it was claimed that nearly three hundred lives had been saved since its introduction in 1839. Blackpool was the first town on the west coast to have one. The vessel was later towed to Fleetwood where it was sold at auction. Further north, beyond Bispham, a body was also washed ashore as if the sea no longer wanted to play around with it. The body belonged to a chap called John Hornby and had been in the sea about seven weeks and was surprisingly very little decomposed.

Some buildings did come down. Part of Dickson’s Hotel was a victim, though here, the confined company of guests and employees were inspired to poetry while the violent storm raged around them, in a scene reminiscent of a ‘Carry On’ film. The Brits have always enjoyed the phlegmatic character attributed to them by other nations, but in order to achieve that reputation they have had to rush headlong into other countries full of adrenalin and flashing sabres so they could create a situation where they could claim to be cool, calm and collected. And its later armies consisted of many a regional Volunteer who had regularly trained in their annual camp at the beaches and sand hills of the Fylde coast. Soon it would be the Crimean War…then India, then Afghanistan, then the Zulus, the Boers, the Boers again then, well, anyone, really. The embankment in front of the hotel was considerably damaged, bit by bit as each line and stanza of the poem, no doubt with the assistance of a drop of wine, was completed as bits of the building dropped off and all, like Joan Simms, ‘feeling a little plastered’. But it wasn’t just this bit of natural embankment that was damaged, it was all the way along until it met the naturally low lying land of the south shore beyond the Yorkshire Hotel where the natural embankment levelled out. Poor old John Worthington, a painter by trade, and probably not inspired to poetry after he had seen one of his buildings collapse. It had been blown down the previous year and before it could be completed again this year, it had been blown down again. Perhaps he should have been a builder by trade instead.

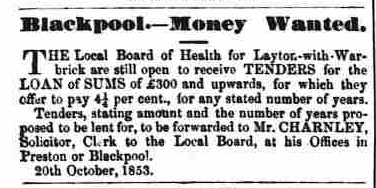

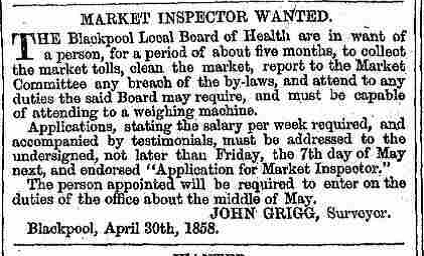

The low lying road in the south shore was completely under water and impassable and the waves crashed against the houses and flooded the gardens. (In 1851 an attempt was made to create a pleasant marine drive between South Shore and its neighbour Blackpool but to no avail, it would need a more substantial effort that could not be afforded in cost and materials at the time). The public walk in front of Benjamin Heywood’s country mansion was awash, and gravel and stone were deposited in front of it in large quantities which took some considerable effort and time to clear after the storm. The sea even reached beyond the protecting palisades of the mansion and enjoyed a little bit of a play within its pleasure grounds. The North Beach road was broken up and left strewn with boulders and other debris when the storm had abated. By the Manchester Hotel, the pleasure boats that had been secured high upon the beach for safety, were shown no mercy as the sea exerted its authority upon them. One went sailing down Lytham Road without a crew, a bath-time plaything thing of the storm.